Analysis: How Ireland changed their defensive system to shut down the All Blacks

Much was made of Ireland’s rush defence, or umbrella ‘outside-in’ tactics to close off the All Blacks attack in the post-match hysteria of the win.

Interestingly, this type of defence is not how Ireland usually defends and not how they played during this year’s Six Nations. There were distinct changes made to dial up pressure on the All Blacks, which is fascinating that they changed the scheme for their biggest test of the year.

Ireland does usually bring line speed but typically play up-and-out defence. In some cases, they will automatically default to a slide defence to account for a numbers disadvantage.

They will generally eat up the space by bursting forward off the line but then slow and hold off, jockey outward and push play to the edge, staying alive as long as possible as a line and allowing the opposition to reveal their hand.

In phases where the opposition has succeeded in creating an overlap, Ireland are willing to concede ground downfield using a jockey/slide system in order to keep guys on their feet and buy time to restabilise the line.

Against Scotland earlier this year, look at how they ‘manage’ the threat of Stuart Hogg off set-piece by playing passive slide defence almost from the start and then re-set to dominate the gain line.

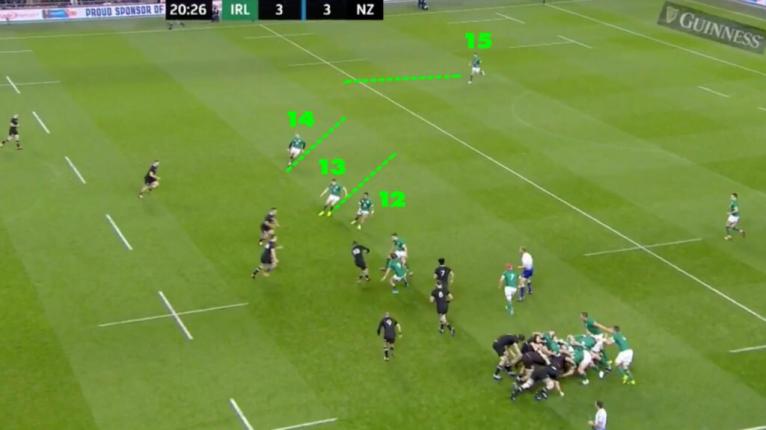

From the lineout, Scotland play wide by using Peter Horne (12) out the back behind a Huw Jones decoy line and succeed in building a three-on-two on the edge, but Garry Ringrose (13) and Keith Earls (14) have already diagnosed the play and are fully aware of this.

They begin to backpedal and bail, happy to give away metres downfield as long as the ball keeps moving wider.

Horne (12) releases the pass without committing any defenders, allowing Ringrose to slide, slimming the assignment down to a two-on-two.

Horne (12) releases the pass without committing any defenders, allowing Ringrose to slide, slimming the assignment down to a two-on-two.

Stuart Hogg carries down the left-hand side for a nice gain but is tackled by the backtracking Ringrose, creating a ruck on the far left-hand side.

Scotland achieve a 20-metre gain on first phase but Ireland’s defensive line is pretty well set for the next phase. Everyone is set ready to now win back the yards from a far more manageable situation.

Ireland’s forwards chew up the space by pressing off the line on the second phase and Scotland achieve a 5-metre loss.

The third phase is the same and Scotland’s runner drops the ball in the face of pressure, conceding a turnover back near the 40-metre line.

With Scotland employing a width game frequently on the first phase, Ireland conceded ground deliberately with a jockey/slide system but never broke, putting Hogg and co. in a shrinking box and choking them out of room to the sideline.

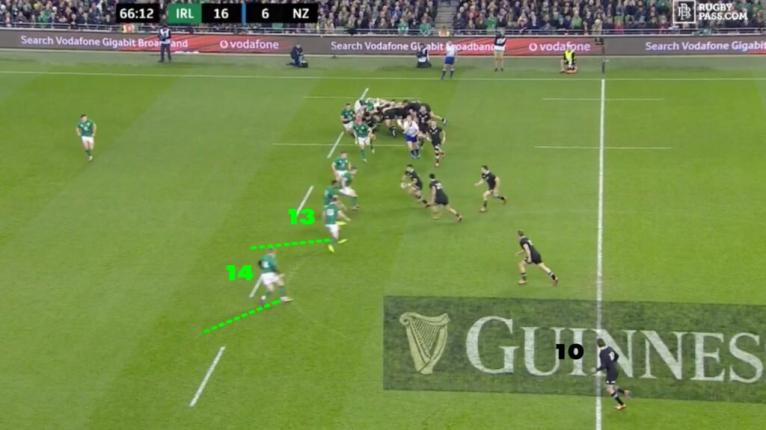

Against the All Blacks on first phase, they played it completely differently. Every scrum play was high-risk rush defence, jamming outside-in to collapse in on the All Blacks midfield.

The statistics will show that a high percentage of the All Blacks scrum plays are part of their ‘javelin attack’ – short-pass midfield crash plays. Ireland seemingly gambled on this information and took the risk to clot the midfield channel.

The ‘outside-in’ rush defence in this situation leaves the fullback completely open but pressures every option inside him.

The ‘outside-in’ rush defence in this situation leaves the fullback completely open but pressures every option inside him.

If the flyhalf is making the pass, a difficult double cutout or kick-pass is required to hit the open fullback. Every other pass is a hospital ball ‘in waiting’ if the outside backs can bring the heat.

Ireland’s centre Garry Ringrose (13) and Keith Earls (14) were phenomenal in pulling this tactic off. It’s highly disruptive in theory but actually executing it and containing the opposition is extremely difficult.

You are effectively leaving the outside channel exposed so you can’t afford to miss your assignment or have the ball get past the centre. However, if you succeed you put the opposition on the back foot with gain line losses.

Earls succeeds in swallowing up Goodhue, but you can see Barrett is left wide open steaming past on the outside.

Ireland did this on every set-piece play, in direct contrast to how they played first phase against Scotland, Wales, and England during the Six Nations.

All of the All Blacks openside scrum plays were to the left, but they were all throttled inside leaving strike weapon Rieko Ioane with zero touches from scrums.

Instead of trying to ‘manage’ the All Blacks’ outside threats with a passive up-and-out line like they do with their Six Nations opponents, Ireland went all-in on preventing the ball getting there in the first place.

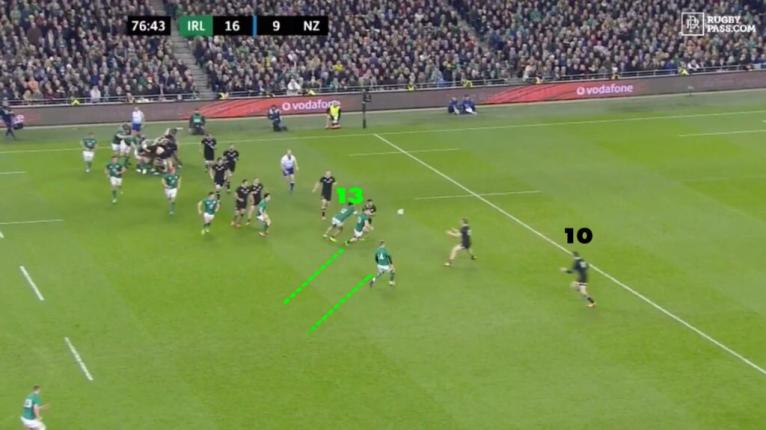

It was prevalent during phase play that this was also a directive.

If we re-visit the Six Nations we can see Ireland’s normal defensive system in place when faced with an overlap.

After six phases Scotland have created a numbers advantage on Ireland’s left edge towards Stockdale’s wing.

Again Horne finds himself with a three-on-two. Conor Murray (9) and Jacob Stockdale (11) push up initially but then play jockey coverage, with hips turned out, backpedalling to buy time and push play to the edge.

For the second time, Horne throws a pass without committing anyone, allowing Ireland’s fractured line to recover and shut play down on the outside.

The pass is wayward anyway and the opportunity is lost. Five minutes later, Horne attempts to throw a long pass without committing anyone for the third time, Stockdale jumps the passing lane and takes an intercept 50-metres the other way.

Against the All Blacks, on a high percentage of plays, Ireland showed a desire to keep the ball inside by continually jamming in.

To maintain this pressure for the full eighty minutes without any lapses in execution was a masterful display of high-pressure defence.

To maintain this pressure for the full eighty minutes without any lapses in execution was a masterful display of high-pressure defence.

Integral to pulling off this tactic was Ireland’s centre Garry Ringrose, who might be the best defender in the game at 13.

His tackle success rate has been elite in 2018 and he showed he is able to execute on different game plans devised by Andy Farrell, playing aggressive or passive as required.

Against the All Blacks, he made 14 tackles and missed one for a 93% completion rate whilst playing high-risk rush defence. To bring that much pressure and execute consistently during any game, let alone against the world’s best, is a testament to his fitness level, determination, and defensive ability.

The back three of Earls, Stockdale, and Kearney also have a huge role to play in Ireland’s defence, each bringing unique talents to the table. Earls is a kick-bait king, Stockdale is a ball-hawk and Kearney covers a huge backfield with anticipatory vision.

Ireland runs a back-three pendulum, but the only constant in the backfield is Kearney.

They trust the wingers to know when to drop into kick coverage, and the supporting cast of Earls and Stockdale aid Kearney well in covering the backfield. In this game, the wingers were tasked with ‘barracading’ the edge more than they usually do, and Earls, in particular, was excellent in assisting Ringrose.

The scariest part of all of this shows that Ireland is thinking two moves ahead of their opponent, looking to stack the odds and adapt their style to whatever they think will work best, and they have the coaches who generally get those decisions right, and the players who can execute it.

Rugby World Cup city guide – Oita: