Raphaël Ibañez: "The day Jonah Lomu taught us a lesson in greatness"

With 2025 shaping up to be the year of Jonah Lomu—marking 10 years since his passing and what would have been his 50th birthday—RugbyPass has decided to honor his legacy with an exclusive, never-before-seen documentary: Lomu – The Lost Tapes. The film will be available free of charge from 1 February on the new RugbyPass app.

To mark the occasion, we spoke with some of those who played alongside “The Bus” during his whirlwind career (63 caps between 1994 and 2002) to share their memories.

On the French side, Raphaël Ibañez, the legendary hooker of Les Bleus (98 caps between 1996 and 2007), was among the first to pay tribute to the iconic winger.

“Immediately, what comes to mind is the memory of an extraordinary player. A player with an incredible balance between the sheer power he displayed on the pitch and the gentleness he showed when I had the opportunity to speak with him,” he tells RugbyPass exclusively.

The man who is now the general manager of the French team has lost count of how many times he played against the legendary All Black—probably five, maybe six.

“Fortunately, he wasn’t my direct opponent. I’d like to spare a thought for the French wingers who had to face him because, as a hooker, I was at the heart of the French pack. Naturally, my field of vision was often limited to the close combat of the forwards. But despite all that, I was—if you can call it that—’lucky’ enough to cross his path on several occasions,” he laughs.

One match in particular remains unforgettable for the man who was then captain of the French team: the semi-final of Rugby World Cup 1999 in England. France’s victory over New Zealand in that game is still remembered today as “the miracle of Twickenham.”

Jonah Lomu nearly missed Rugby World Cup 1999

“In 1999, his reputation was that of an outstanding, exceptional player at the peak of his strength. He was the X factor in this fabulous New Zealand team,” recalls Ibañez. Yet, in reality, Jonah Lomu almost didn’t take part in that World Cup—something the world would only learn much later.

For several years, Lomu had been battling nephrotic syndrome, a rare kidney disease (affecting roughly three people per 100,000 each year). The heavy treatment he was undergoing limited his ability to perform at his best, but he was determined to fight through it.

In the summer of 1999, while New Zealand were dominating the Tri Nations and cementing their status as favorites for Rugby World Cup in England, Lomu was struggling. Replacing Tana Umaga and Daryl Gibson, he found it difficult to make an impact and failed to score a single try in four matches.

Though eventually selected for the World Cup squad, he wasn’t at his best and didn’t experience the tournament the way he would have liked. But the All Blacks kept that secret well-guarded—because, above all else, Lomu had to remain a figure of fear. That was the message they needed to send to the world.

“At that time, the information circulating between the southern and northern hemispheres was rather vague, sometimes even confused. We had very little real information about our opponents, whether about their way of life or their preparation,” recalls Ibañez.

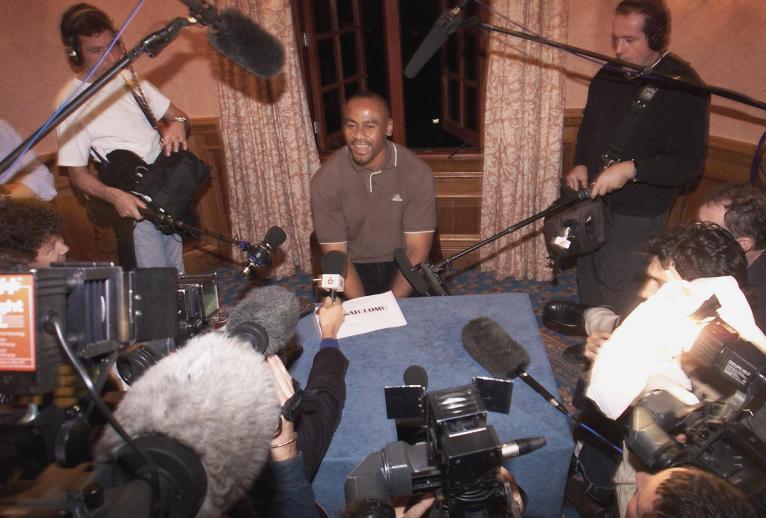

(ELECTRONIC IMAGE) (Photo by OLIVIER MORIN / AFP) (Photo by OLIVIER MORIN/AFP via Getty Images)

“Of course, with the rise of technology and video analysis, that was about to change. But back then, it was difficult to obtain precise details about a player’s personality, daily life, or even health. In fact, I don’t think anyone in the French team of my generation was really aware of Jonah’s health problems.

“And yet, watching him play, there was no sign of anything. He was always a major topic of discussion before matches, but only from a sporting perspective. The only question was: how to stop him.

“He was a phenomenon, a force of nature surging down his wing like a hurricane. Finding a way to contain him was a real headache, and it gave our backline plenty of sleepless nights for years.”

Playing the All Blacks helped overcome tensions within the French team

Raphaël Ibañez confirms that the French national team was indeed searching for an “anti-Lomu plan” on the eve of the semi-final.

“To tell the truth, there was quite a bit of tension in our squad. The group was made up of strong personalities, and we struggled to channel our energy into pure performance,” admits the former captain.

“But that all changed when we found ourselves up against the ultra-favorites, New Zealand. It forced us to adopt a much more studious and rigorous approach.

“And beyond the tactical aspect, on an emotional and motivational level, we had this deep conviction that our strong personalities could, in that moment, achieve something extraordinary. We knew that in the ultimate competition, in a knockout match, we would be able to push beyond our limits.”

And that’s exactly what happened at Twickenham on 31 October 1999, in front of nearly 73,000 spectators.

France on the losing side

“The plan was very simple: to put our wingers, Philippe Bernat-Salles and Christophe Dominici, in the best possible mental condition to rise to the challenge and take on Jonah Lomu,” reveals Raphaël Ibañez.

“From a purely tactical point of view, the objective was clear: to cut off, as much as possible, the connections between New Zealand’s back line, which was remarkable, by the way, and the phenomenon that was Jonah.

“The idea was to prevent him from receiving the ball in ideal conditions. Because once it was in his hands, there was only one solution: to be very solid.”

Against the Black Mountain, France’s chances seemed slim. The fear of missing out on the match loomed over everyone, especially after a disappointing Six Nations campaign and a complicated June tour.

“Beyond the bookmakers’ predictions, a French newspaper even conducted a mini-survey—not to find out if we were going to win, but to guess by how many points we were going to lose to New Zealand! Can you imagine the level of confidence back home?”

And then, the unthinkable happened. A spontaneous Marseillaise, sung by the players in response to the haka, ignited Les Bleus.

“At the time, it was a cry from the heart, a spontaneous outpouring of pride in representing our country and our shirt. We did it freely, instinctively, but there was also a very strong symbolism behind it. Singing together, among ourselves, was a way of affirming our unity. For us, it was also a form of rebellion, a desire to assert ourselves at that precise moment,” recalls the captain.

Jonah Lomu’s second try was the catalyst for the revolt

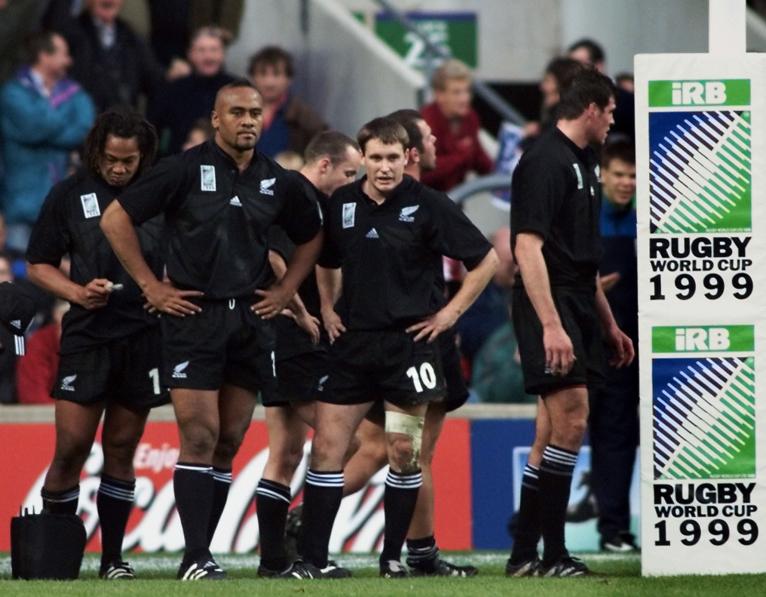

The match quickly turned against the French, who found themselves trailing 17-10 at half-time, compounded by two yellow cards (Garbajosa in the 17th minute and Ibañez himself in the 35th). But in the second half, everything changed. Between the 45th and 65th minutes, they scored 33 unanswered points.

“Looking back, I think everything shifted after Jonah’s second try in the 45th minute, which seemed to seal the fate of the match,” says Ibañez.

“At that moment, we were standing under the posts. And you know, under the posts, there’s always that crucial moment when players need to speak, to lift each other up. The words that come out then, whether from me as captain or from the team leaders, go beyond simple motivation. We were talking about survival.

“We knew we had two choices: either we let go and prove the bookmakers right—those who already saw us miles behind the All Blacks—or we ignite that survival instinct, that force that pushes us to surpass ourselves.

“And then the game took over. The ball, the rebound, the opportunities that suddenly opened up. The momentum shifting. The look of doubt creeping into our opponents’ eyes. The songs reverberating through Twickenham…

“All of that still gives me an indescribable feeling. It was something incredible, extraordinary in the purest sense of the word—a moment that broke away from the ordinary, that transcended us.

“So yes, people often talk about the magic of Twickenham… But that day, we were the ones who wrote it.”

Jonah Lomu’s unforgettable gesture at the end of the match

At the final whistle, the All Blacks were in shock. They had been eliminated, 31-43. Only one man remained standing, with dignity, full of respect. It was Jonah Lomu. He was the first All Black to step forward and congratulate the winners.

“I’ll never forget that moment,” confides Raphaël Ibañez, still moved more than a quarter of a century later. “We were caught up in a kind of whirlwind, a collective euphoria, a form of magic.

“And then, in the midst of all that excitement, there was this striking gesture. While some players, understandably devastated by being knocked out of a World Cup, left the field, Jonah took his time. He took a deep breath, then came over to greet us and shake our hands.

“It was an incredibly classy gesture, a demonstration of respect and connection between men who, once the battle was over, were simply men again.

“That moment left a deep impression on me. When you prepare for this kind of match, you put everything on the table—your energy, your talent, your pride.

“And Jonah taught us a lesson. A lesson in greatness. Beyond the competition, the confrontation, and the rivalry, he was able to set aside his disappointment and his pride to honour his opponent with respect.

“It was a gesture that touched my heart, and one I will never forget.”

The two players crossed paths several times in the years that followed, and Raphaël Ibañez has never forgotten the “absolute contrast” that made Jonah Lomu such a unique figure.

“On one hand, he had exceptional strength, a raw talent capable of shining on any pitch in the world. On the other, he had an incredible kindness, a gentleness and accessibility that contrasted with the image of the unstoppable colossus.

“This contrast touched me deeply because it reflects something you find in many rugby players—that duality between the ability to fight, the drive, to dominate an opponent physically and mentally, and then, off the field, that positive energy, that deeply human side.”

Jonah Lomu passed away on 18 November 2015 from a heart attack. He was 40 years old. He had just returned from attending Rugby World Cup 2015… in England.

The new RugbyPass App is the home of rugby. Offering fans a one-stop solution to enjoy the game they love, how they want it. Download today from the App Store (Apple) or Google Play (Android).

News, stats, live rugby and more! Download the new RugbyPass app on the App Store (iOS) and Google Play (Android) now!

Great article about two gentlemen and the rugby values