What went wrong with Argentina at the Rugby World Cup?

In a year in which the Jaguares made the Super Rugby final, Argentina are now destined to unceremoniously crash out of the pool stages in Japan, despite being largely made up of the same players.

The result is the culmination of a horror 12 months for Los Pumas where they seemed to take one step forward and two steps back. The watershed win over Australia on the Gold Coast in 2018, their first-ever on Australian soil, was supposed to be the breakthrough moment for a tier one nation on the rise.

Instead, they followed that up with nine straight losses including a second half meltdown in Salta against the same Australian side, giving up a 31-7 halftime lead. They finished 2018 with a winless end of year tour with losses to Ireland, France and Scotland.

Continue reading below…

Their performances in the truncated Rugby Championship this year – two close losses followed by a hiding at the hands of South Africa in Salta – gave no indication that they would arrive at the World Cup in great form.

The obvious observation is that international rugby is not Super Rugby, but a slightly less obvious one is that the same players with different coaches can provide vastly different results.

In a year in charge of the Jaguares in 2018, Mario Ledesma achieved some ground-breaking wins in New Zealand and finished with a 52.9 percent win rate, better than his predecessor Paul Perez at 36.7 percent.

With largely the same Jaguares squad this year, Gonzalo Quesada achieved an even better rate, winning 68.4 percent of their games and taking them to the final. It seemed as though this core group of players were ready to produce at the next level.

Back under Ledesma at international level, those same players playing for Argentina have struggled, looking less organised and less stable than they did wearing black and orange.

They have failed to score more than one try in seven of the last nine tests against tier one teams over the last year. The Pumas’ win over Tonga was the first time they have scored four tries in a test since the Salta meltdown.

This year has seen Argentina creep towards more conservative play, keeping it tight away from their dangerous outside backs and preferring narrow attack, flat off nine from set-piece platforms.

This has often resulted in turnovers as players struggle with handling playing extremely flat charging at the line. Cubelli’s direction from the base of the ruck has been amiss, banging the side into brick walls with one-out runners after one-out runners.

This has cost Argentina early in both crucial pool stage matches.

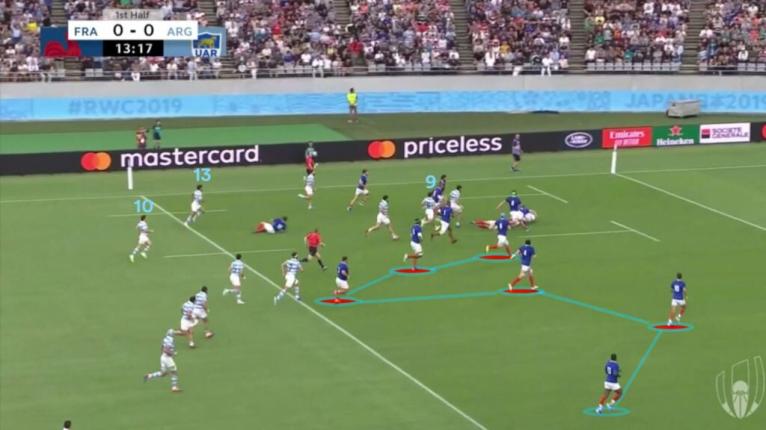

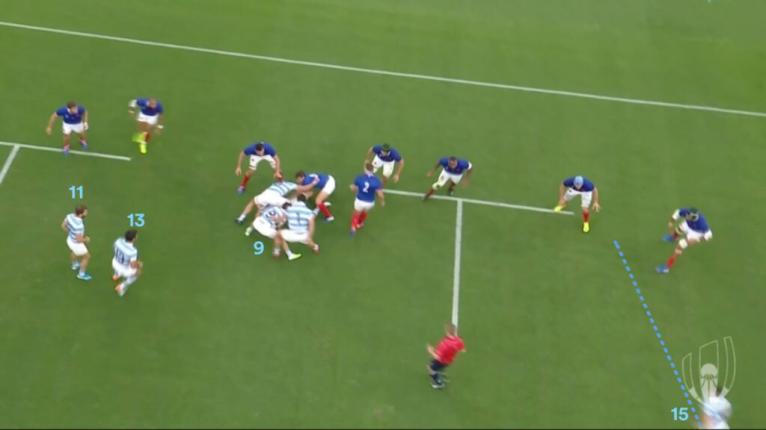

Lock Guido Petti Pagadizaval makes a break deep inside French territory down the left side, an ideal situation for ‘hot ball’ swinging back to the right where the defence is staggered and still retreating.

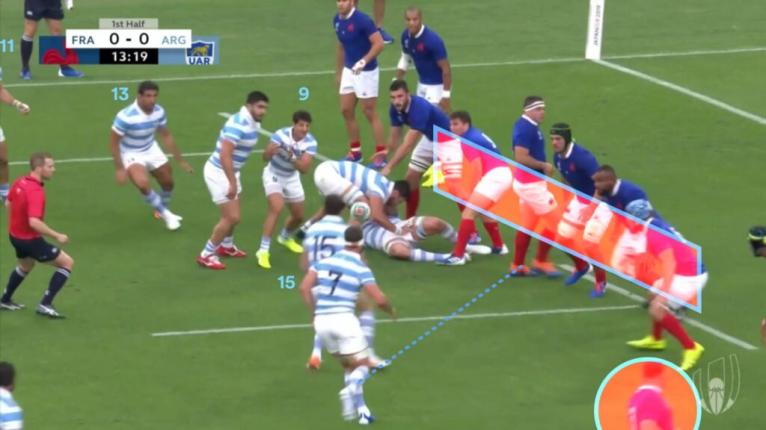

Tomas Cubelli is already at the ruck, but flyhalf Sanchez is slow to get downfield to organise an open side play. Centre Matias Orlando is also not preparing on the open side and ends up in ‘no mans land’ as a rather redundant option close to the ruck.

Cubelli fires a flat ball to fullback Boffelli running hard directly into a blue wall, the most crowded spot in the French defensive line which still has players retreating wider.

Cubelli fires a flat ball to fullback Boffelli running hard directly into a blue wall, the most crowded spot in the French defensive line which still has players retreating wider.

This is a classic example of an underperforming side creating space and proceeding to not use it with poor option-taking and a lack of organisation.

Argentina eventually go wide on the next phase after Boffelli’s carry, one phase too late, and find nothing.

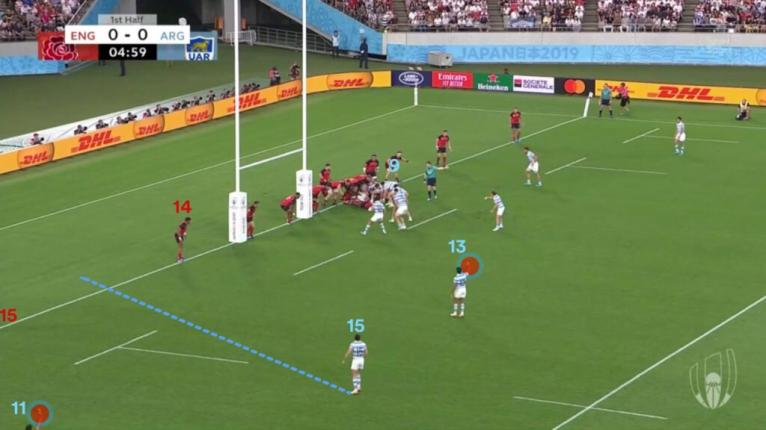

The same thing happens early on against England with the Pumas attacking after a scrum where England have crowded numbers around the ruck.

Holding a penalty advantage, the outside backs realise the space is left with two players calling for the ball with their hands up.

Only Anthony Watson (14) and Elliot Daly (15) are left to cover half the field. With straight-line running and simple hands without cutting out anyone to hold the defence from drifting, Boffelli (15) would likely find the gap outside Watson with Daly (out of the picture) forced to cover two men.

Instead, Cubelli hits another tight runner in close giving England another phase to fan out.

When they do go wide again one phase too late, the outside backs expect a cross-kick, butchering the timing when Benjamin Urdapilleta throws an ill-advised cutout pass. The static ball enables England to scramble just enough to get Santiago Carreras into touch when the winger does eventually get the ball.

The narrow stuttering attack has been complimented by poor kicking. In the first half against France, they tried an aerial assault, taking the blueprint from England from the Six Nations but failed to execute well. Sanchez was below par with his game management, kicking out on the full once and dropping the ball cold after bailing on the bomb option.

More aimless kicking followed, as they struggling to get contested kicks while Emiliano Boffelli struggled to secure possession from a barrage of French ones.

As a result, Argentina was left to defend for long stretches and looked out on their feet after 20 minutes. With electric halfback Antoine Dupont sniping, France killed Argentina down the thin short side around tired defenders and France went up 20-3.

They were able to get back in the game via French ill-discipline more than anything else, mauling over for two tries off the back of penalties kicked to the corner.

A telling stat is the non-involvement of the wingers against France, with Ramiro Moyano finishing with two carries for four metres and Matias Moroni three carries for four metres. The forwards combined for 50 carries compared to just 16 across the outside backs.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B3O7dbwAuMs/

In 2018, Argentina were adept at playing possession-based rugby with a 1-3-3-1 system.

They played a bit deeper off the halves, showing fast-ball movement with developing catch-pass skills that utilised quick handling and deft touches against the oncoming rush defence.

This suited the likes of back rowers Javier Ortega Desio and Pablo Matera, who are avid promoters of the ball on the edge.

Either on short sides switching play back outside the 15 metre tramlines or on the third phase the same way, Argentina played a patient game that eventually worked wide to free fleet-footed danger men like Ramiro Moyano and Bautista Delguy. The attention Desio and Matera command one-in often gave their wingers the space they needed to make game-breaking runs.

Their phase play was evolving and gave a sense of control with time in possession often in their favour when executing well.

It was a perfect model to compete against the All Blacks, where Argentina have been able to stay in the game for upwards of 50 to 60 minutes but missing the conditioning and accuracy under fatigue to go the distance.

It seemed to be a style of rugby that played to their strengths and looked to get the ball in the hands of X-factor players. Boffelli also had built a combination with Sanchez to use a pop pass play in central zones as part of this pattern.

At this World Cup, we have seen Argentina more skewed towards territory-based rugby from the middle third of the field and one-dimensional play in attacking zones, reverting to a foreign type of rugby.

Argentina has never been a team that kicks tactically well after possessing the ball for multiple phases, and this has also been true of the Jaguares at Super Rugby level, but the side has done this repeatedly in the key pool stage matches. The key game drivers responsible for this – Tomas Cubelli and Nicolas Sanchez – haven’t been in great form for Argentina this year and this has come to the surface.

Poor execution has let them down, but also a factor at play has been the inability to use the special talents of their best attacking players like Matera, Moyano, and Boffelli.

That has come down to the schemes employed in the red zone and middle third of the field.

Argentina didn’t beat Ireland in the 2015 World Cup quarterfinal after dialling up the number of forward carries off nine and kicking the ball away excessively.

Perhaps re-finding the identity of the team that has generally over-achieved at World Cups would be the starting point to getting back to that stage of the tournament again.

Scotland train before their next World Cup clash: