The speed of professional rugby is increasing all the time. Every tweak in the laws is designed to make the game quicker, and increase the amount of ball-in-play time. Charting progress over World Cups, an average of 25 minutes of ball-in-play at the first tournament of the professional era in 1995, had risen to almost 35 minutes at the latest iteration in 2019.

At the same time, the proportion of breakdowns has increased as the number of set-pieces has dwindled. At the 1995 World Cup, the ratio was one to one, by 2019 it had exploded to four rucks built to every scrum or lineout set.

The latest revamp of the laws in and around the contact area occurred in 2020. They are comprehensively explained here by New Zealand Referee Manager Bryce Lawrence and current NZRFU official Paul Williams.

They have already had a profound impact on the English Premiership, where there has been an upsurge of coaching interest in faster recycling at the ruck and ‘lightning-quick ball’ (LQB).

The three knockout games of that competition (two semi-finals and one final) produced a total of 227 points, at an average of 76 points per game, and 31 tries at an average of over 10 tries per game. There is no longer anything remotely stodgy about Premiership rugby – far from it.

The scrum is the last bastion of slow tempo, set-piece oriented play. Throughout all of the many transformations of Rugby in the professional era, it has stubbornly refused to conform. In fact, its refusal to produce usable attacking ball has only hardened as time has passed.

At the 1995 World Cup, an average of 23 scrums per game were set and only 10 per cent of them ended in penalties. By 2019, the numbers had changed radically: only 14 scrums were set, but 26 per cent of those set-pieces finished up as penalties. The amount of usable ball presented from the scrum has effectively halved.

Instead of trying to use the ball from scrums, teams tend to accrue penalties, mostly from the movement of the scrum on its natural axis around the loosehead side. At the 2019 World Cup final between South Africa and England, the Springboks won five penalties on their own feed and that was a major plank in their platform for success.

Even though the English Premiership final between Exeter Chiefs and Harlequins was an eleven-try spectacular in the afternoon sunshine, six of the 12 scrums set still ended in penalties. While the rest of the game is moving towards the light, the scrum remains stuck in the dark ages.

The following example was typical:

It’s a good scrum, no doubt about it. It goes forward on both sides for a full five metres until the structure in the front row finally breaks up and the referee feels compelled to award the feeding team (Harlequins) a penalty. The incentive to play the ball away from the set-piece is not strong enough to persuade a side as constructive as Quins to do anything other than win a penalty, march into the Exeter 22 and start from a lineout instead.

World Rugby needs to construct a similar refereeing scenario at the scrum to the one it has promoted at the breakdown. The rewards for playing the ball at set-piece have to become more attractive than those available for not playing it at all.

The one ray of light from recent matches is the ‘lightning quick ball’ obtained from the scrum by the Japanese national team. Japan, under their progressive New Zealand coaches Jamie Joseph and Tony Brown, know that they are not big enough to grind the opposition down and scrum for penalties. They use ‘channel one’ and play it out instead.

Channel one does not go to the number 8’s feet, it emerges far more quickly from the space between the left-side second row and flanker. Either the number 8 moves across to play it from that space, or he does not touch it at all.

Channel one ball has been neglected for much of the professional era. As evidenced in the example from the Exeter-Harlequins final, when the ball is kept in at scrums, and the secondary shove applied, it tends to go to the number 8’s feet first.

Channel one does not go to the number 8’s feet, it emerges far more quickly from the space between the left-side second row and flanker. Either the number 8 moves across to play it from that space, or he does not touch it at all.

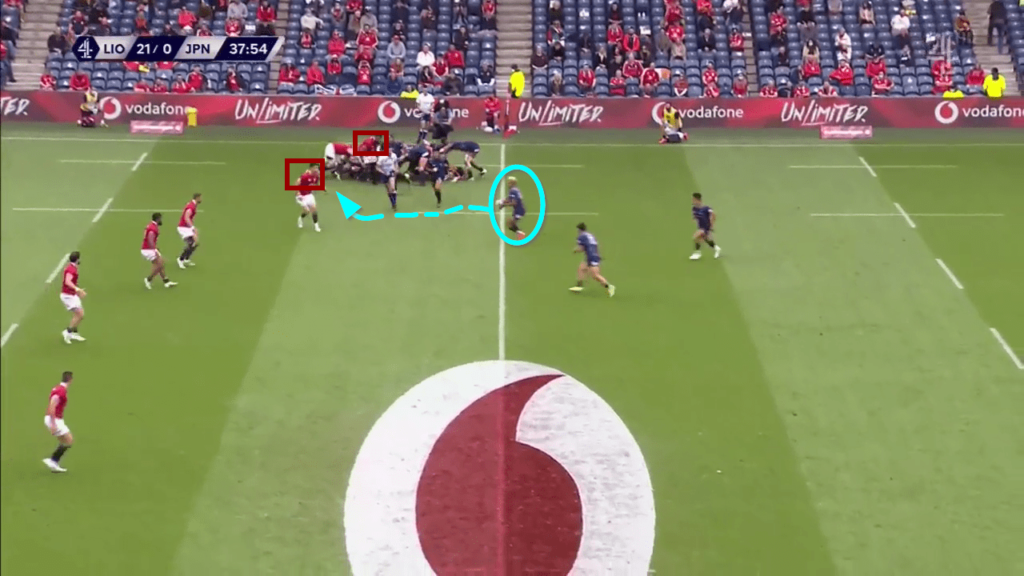

Japan’s game against the British & Irish Lions gave the first hint of the advantages this channel can provide, especially from scrums set on the right-hand side of the field:

The Japanese number 8, Amanaki Mafi, does not interfere with control of the ball at all as it pops out between the second row and openside flanker, and under the current rules, the scrum-half is allowed to play it before it reaches the hindmost foot of the scrum.

The move is a simple insertion of the blindside wing (number 14 Kotaru Matsushima) into first receiver, but he is running into a space which has been dramatically widened by the use of lightning quick ball from channel one:

At the moment Matshushima receives the ball from his half-back, the Lions’ openside flanker, Taulupe Faletau, has not even raised his head, let alone detached from the set-piece, leaving the defensive scrum-half, Conor Murray, with ten metres of space to defend. For an attacker with Matsushima’s quick feet, that is too big of a gap for Murray to cover.

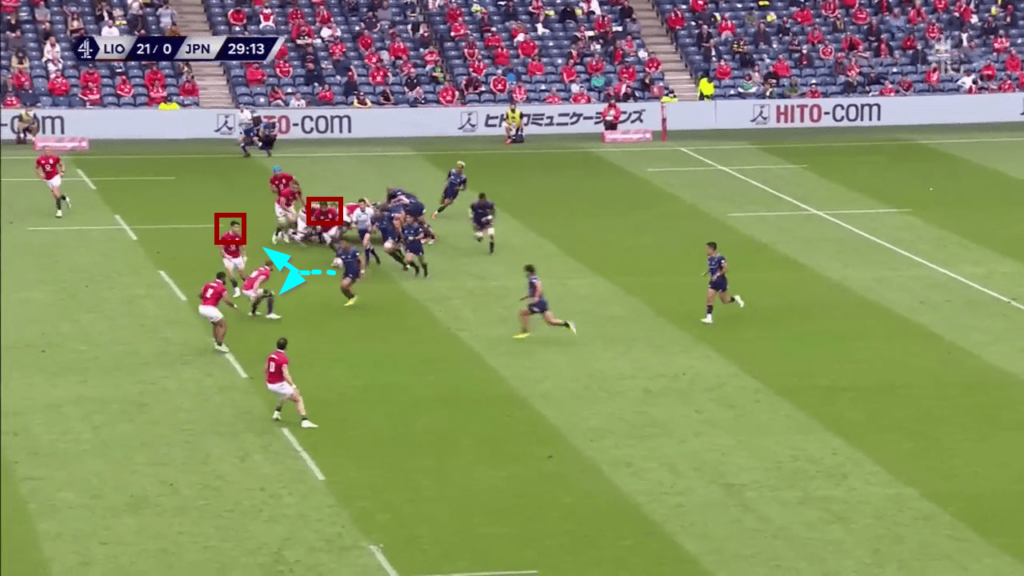

In fact, it had been there on the preceding set-piece, even though it was left unexploited:

Japan expanded the same theme to even greater effect the following week. They gave Ireland all of the trouble they could handle, and more at the Aviva Stadium in Dublin last Saturday. Once again, one of the core platforms for their success on attack was the use of ‘channel one’ ball from the set scrum on right-to-left movements:

The ball does not trickle back slowly to the number 8’s feet for a ponderous secondary shove and a penalty win, it emerges in the space between the left second row and flanker.

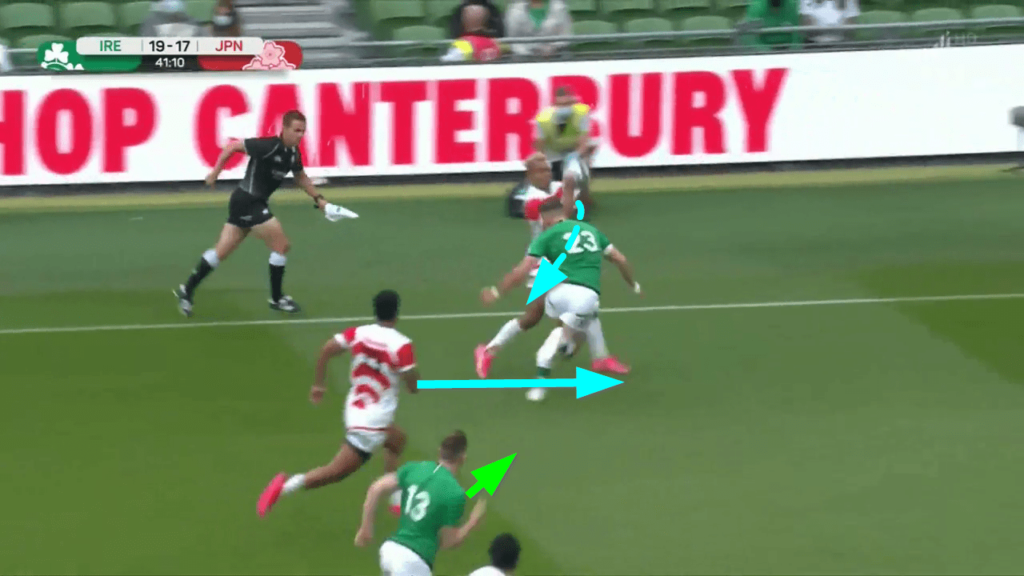

On this occasion, the zone of attack is different to the joint between the defensive 7 and 9. The Ireland scrum-half Jamison Gibson-Park is well into his backpedal, but the speed of delivery from the set-piece shows that immediate space is available out wide.

As in the examples from the Lions match, one of the bonuses of channel one ball is that it tends to promote the critical support players ahead of the defence. The Japan No 7 was off the side of the scrum quicker than his opposite number, and enjoyed the inside track in support of the ball-carrier against the Lions. Against Ireland, the inside support is already winning the race to the ball-carrier, if the offload can be executed successfully:

A couple of minutes later, Japan found the finishing touches which had been lacking in the previous sequence:

‘Width’ does not just mean one-phase width. The ability to stretch a defence can carry over strongly to second or third phase.

In this instance, Ireland have been forced to pull their fullback into line earlier to combat the quick width off channel one Japan, and that means nobody at home in the emerald green backfield for the following phase. A beautifully nuanced kick-through provides the gloss on the score after the break is made.

With the Irish fullback already absorbed at the first ruck, the blind-side wing is the only defender left to intervene on second phase:

The idea that channel one ball can generate enduring difficulties for the defence over more than one phase, and create gaps they cannot cover, was repeated in the latest test match between Australia and France on Wednesday:

The ball emerges from the scrum from underneath the feet of Michael Hooper, the Wallabies’ openside flanker. That in turn creates the space for the Australian blindside wing (Tom Wright) to engage the France number 10 (Louis Carbonel) on first phase.

The knock-on effect on the following play is that only two French forwards, rather than the typical three, have made it around the corner of the first ruck:

An inviting gap has opened up between the two France back-rowers and No 12 Jonathan Danty, which Australian centre Hunter Paisami is able to exploit with an angled run.

The game of rugby is speeding up. Ball-in-play time has increased in leaps and bounds from the beginning of the professional era back in 1995, and the ratio of rucks to set-pieces is multiplying in favour of the breakdown. Those rucks are already resolving faster under the new ruck directives.

Only the scrum stubbornly refuses to produce quick ball. As a general rule, teams lack the incentive to do much more than win penalties from the set-piece and start from a lineout instead.

Japan’s emphasis on winning quick channel one ball is a sliver of light in the prevailing darkness. If the refereeing of the scrum can be shaped to force a play-the-ball rather than a whistle-stop finish, it may become the norm rather than the outlier. Now that really would be a sunlit emergence from one of the last remaining dark corners of the game.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free