In the old days, an Irish tight-head used to unfailingly stay true to the stereotype.

He wore a moustache and wrangler jeans. His face was covered with faint bruises, thin scars and the cheesiest smile in the clubhouse.

He talked more about the dark arts of the front-row than the renaissance arts of the 16th century. He didn’t like to move, either from his stool at the bar or around the pitch. His scrummaging got better with age; the wine he bought from Aldi didn’t.

He knew every trick that went on inside the scrum but wasn’t as detailed about events in the outside world.

He may have been the life and soul of the party but pity the innocent who crossed him. They’d soon see the smile replaced by a sneer, the kind you’d associate with a Bond villain in Goldfinger or Live and Let Die.

Mentioning his figure was never a good idea, either, because while these old tight-heads may not have appeared to be the sensitive type, do you think they appreciated being told they were out of shape? Fat chance.

It was like learning to write with my other hand

Andrew Porter on switching from loose-head to tight-head prop

A few traditionalists, seduced by their courage and scrummaging expertise, miss these players. They see Tadhg Furlong unleash his inner Phil Bennett by sidestepping his way past a couple of Scottish defenders and yearn for the day when tight-heads drew pleasure from hitting and hurting rather than evading.

If the last thing these old-timers want to see is a man with a three on his back delivering the gentlest of touches in open play then the second-;ast thing they want is a Johnny-Come-Lately who adapts to the position with the comfort of a duck being introduced to water.

So we’re unsure then whether this is the best or worst time to introduce you to Andrew Porter, Furlong’s back-up with Leinster, Ireland, and now – much to the consternation of Kyle Sinckler fans – the British and Irish Lions.

If you are one of those who find it hard to believe the man who’ll see out the three Tests in South Africa isn’t Sinckler, then you’ll probably find it even more difficult to get your head around the fact that only four years have passed since Porter first tried the position.

Worse again, it happened by chance. Rassie Erasmus – now the Springboks director of rugby – was trying to reinvigorate Munster in 2016 when he spotted Porter in an Ireland Under-20 shirt at that summer’s Junior World Cup. An effort was made to sign him, prompting Leinster to promote Porter to a senior contract.

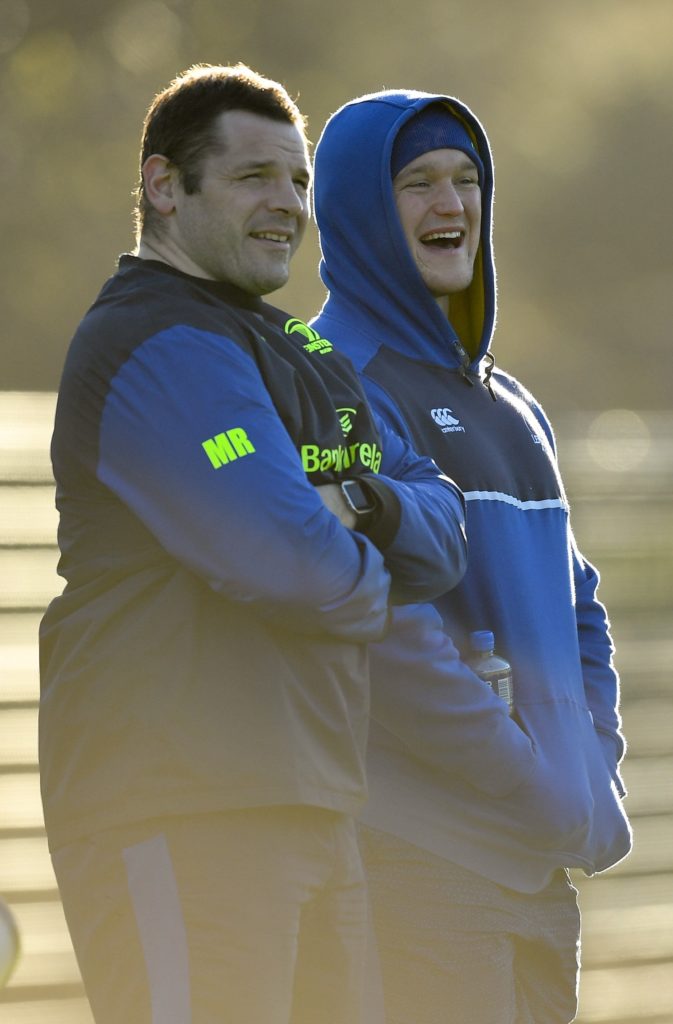

Still, there were roadblocks in place. At this stage Porter was a loose-head, a congested area in the Leinster dressing room, prompting the club’s scrum coach, John Fogarty, to ask Mike Ross, a veteran of two Heineken Cup wins and over 50 Ireland caps, to suggest a prop capable of switching across the front-row.

Porter was the name Ross came up with – which inadvertently ‘sealed my fate as a result’. The veteran was moving towards the end of his career; Porter’s accelerated rise brought forward the retirement date.

Yet you wouldn’t have predicted that the first time he tried this new position. “It was like learning to write with my other hand,” Porter said of his tight-head debut in the All Ireland league, the then 21-year-old outplayed by a much lighter but more streetwise amateur, Young Munsters’ David Begley. “You’d know he was starting out,” said Begley of Porter’s relocation. “But he’s a big man. Hard to move. He’s done well for himself.”

That’s saying something. Convention says it takes years of schooling before a player is ready for Test rugby at tight-head. Porter completed his education in 11 months, coming off the bench just three minutes into Ireland’s Six Nations win over Italy in February 2018, starting the following week against Warren Gatland’s Wales. Not only did he survive; he shone. “A special performance,” said Joe Schmidt afterwards. “It takes character to make that transition appear so seamless.”

What Schmidt knew – and the rest of us then didn’t – was that Andrew Gerald Porter had already adjusted to something infinitely more serious.

All that distress and anguish made me who I am. I wish my mum was here every day; I have tough days

Andrew Porter on losing his mother to cancer

The burden that Andrew Porter once carried on his left shoulder has been replaced by a tattoo. It is of a Roman monument he went to see with his mother, Wendy. His mother’s name is also inked onto his forearm as well as a rose and a dove. On his right arm is a tattoo of Saint Michael, his guardian angel.

He was 12 when his mother died from cancer, the day before he started secondary school, where under the kind eyes of a Physical Education teacher, David Jones, the gym became his refuge. Grief can flood through a person at any age but can you imagine the torment a child experiences when love and joy gets thieved away?

When things were at their worst, Porter would suffer from an eating disorder, the biggest kid in the class becoming one of the thinnest. He’d recover. The gym, the weights, the care of a mentor’s words, the reward of getting a return on his physical exertion, all helped mould the boy into a man, and not just physically.

“All that distress and anguish I went through, is what made me who I am,” said Porter in an interview with The Irish Independent in 2019. “I wish mum was here every day; I have tough days.”

He has help fighting through them. His Ireland debut in New Jersey? Dad Ernie, a centre with Carlow and Old Wesley in his younger days, was there for that. The 2018 Grand Slam? Ernie made it across to Twickenham. The Champions Cup win that same year? Ernie was in Bilbao.

“I learned that despite such an all-consuming loss, a person’s family will be there, no matter what,” Porter said in that 2019 interview. “Family is everything to me; it was them who got me through losing mum. Children going through a loss need to talk about it.

“I didn’t want to talk, as I thought people would think less of me but it helps. It’s a macho thing, not to talk, some guys still think they can’t talk about their problems but that was the mistake I made, bottling it up all those years.”

If talking helped, so did rugby. Most kids in Ireland start mini-rugby when they are seven; Porter was big enough to begin at five. St Andrew’s, a school he shared with fellow Ireland international Jordan Larmour and another player who’d turn professional, Ulster’s Greg Jones, was a haven.

Progress came along predictable lines: the school team, the Ireland representative sides, the Leinster academy, club rugby in the All-Ireland League with UCD and then, in March 2018, on just his fifth start as a tight-head, against Wales in the Six Nations.

“Being a tight-head,” Furlong once said, “requires a maximal effort, like holding your heaviest squat for an extended period – but you’re also using your chest, your neck and your back. The wind is zapped out of you. You nearly feel a bit groggy. Then suddenly you have to motor around the pitch. That can be tough.”

That Porter coped didn’t surprise Darragh Fanning. The former Leinster wing is like a latter-day version of Rocky Balboa, a gym salesman who got his chance to play for his home-town club almost by chance, a chain of events resulting in him getting a short-term contract in 2013 and ending up staying there for three years.

Yet because Fanning had arrived so late into the season, the only locker left available was down in the corner, where the kids from the academy sat. The then 27-year-old didn’t mind. “It wasn’t precisely hardship,” he says. “I was living the dream.”

He wasn’t to know it then but life in that corner of the Leinster changing room afforded him a window into the minds of kids who’d turn into stars. Furlong’s locker was across the way. “Great fella, great confidence about him,” says Fanning, who would later sit and get changed alongside emerging stars like Dan Leavy, James Ryan, Josh van der Flier and Porter. And time after time, year after year, the quieter ones in the changing room tended to be the ones with superstar potential.

The thing with Ports is that he is so strong that no-one is going to outmuscle him. Once he’s set nice and low, you’d need dynamite to shift him

Mike Ross on Andrew Porter’s strength

Porter fitted into that category. Cian Healy was considered the gym king at Leinster. Then Porter arrived as a kid out of school and was quickly squatting 300KG reps. “The ones who did the extra work, they invariably have been the ones who’ve risen to the top,” says Fanning.

Porter’s graft was paying off. “The thing with Ports is that he is so strong that no-one is going to outmuscle him,” said Ross. “Once he’s set nice and low, you’d need dynamite to shift him.”

Tellingly no one has shifted him from the Ireland squad since that 2017 debut on the tour to the US and Japan and playing second fiddle to Furlong didn’t bother him as, over the last four years, he has averaged over 700 minutes per season with Leinster as well as eight caps per year with Ireland.

Some days went better than others, last season’s Champions Cup quarter-final against Saracens being a particularly tough one. Yet he bounced back, profiting from Furlong’s year-long calf injury to start eight games in a row for Ireland after getting just four starts in his first 26 Tests. “Every day, you get 100 percent from Ports,” said Ireland coach, Andy Farrell, earlier this year. “Match-days, the bigger the occasion the better. He delivers.”

The stats reinforce this claim. Aside from anchoring a scrum, he was delivering impressive numbers around the park, putting in 12 tackles in 25 minutes against the Scots; carrying for more metres against Wales than any other front-row.

Little wonder he has stated how the days of ‘just a scrumming tighthead’ are over; piano movers these days are also asked to play a few tunes before finishing their shift. “The main thing is knowing your role especially when you come off the bench,” said Porter. “I just try and get on the ball as much as I can and get into the flow of the game.”

Against this backdrop, choosing a highly competent, ego-free talent to tour with the 2021 Lions has its logic. The trouble is, not everyone agrees, much being made of Sinckler’s emotional response to being left out when he was interviewed by BT Sport a few days after the squad announcement.

“Certainly it was a big call, in the sense that players from other countries will look at the fact that Porter isn’t even number one with his club,” said Eddie O’Sullivan, the former Ireland head coach who was Clive Woodward’s assistant on the 2005 Lions tour to New Zealand. “But I agree with the decision because, okay, he is a back-up but look who he is back-up to – Furlong, the best tight-head in the world. In his own right, Porter is a brilliant operator. He won’t let anyone down.”

Plus he offers positional flexibility, with whispers circulating in March that he’d be asked by Ireland and Leinster to switch back to loose-head. “That’s a tricky one,” said Robin McBryde, Porter’s scrum coach at Leinster and also one of Gatland’s backroom team members. “What you don’t want to do is mess around with somebody like Ports. He’s a great kid to work with because he is so open to anything really.”

For now, chat of experimentation will cease until after the summer. There’s a tour to look forward to, a point to prove. Being Leinster’s second best tight-head doesn’t stop him also being the second best in Britain and Ireland.

Nor does it stop him remembering where he came from. After the squad announcement, Jones – his gym mentor during those dark, teenage years – sent him a congratulatory text, reminding him how his hard work had paid off, a story beautifully told by Cian Tracey in the Irish Independent.

“He replied to say he remembers who helped him along the way and I just thought that was lovely and really summed up how humble he is,” Jones said. “My only response to him was ‘All you, Andrew. You have always been a Lion and just pulling on the jersey really just makes it official.’

“His attitude, the tragic circumstances in which he started school and where he is now, he was destined to do this. For me, he has always been a Lion.”

More stories from Garry Doyle

If you’ve enjoyed this article, please share it with friends or on social media. We rely solely on new subscribers to fund high-quality journalism and appreciate you sharing this so we can continue to grow, produce more quality content and support our writers.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free