When Ali Price lofted the ball into the Cape Town sky during the third Test, it stayed air bound for just under four seconds and carried 20 metres. Two players leapt for the ball. Clad in red was the chasing Duhan van der Merwe. In green, Jasper Wiese, jumping from a standing start. The ball ricocheted several feet upwards. In the ensuing melee, Lukhanyo Am reacted quickest, turned defence into attack and 11 seconds later Cheslin Kolbe dotted down for a sublime series-defining try.

The human eye was unable to pick out whether the airborne ball had travelled forward, leaving fans of both sides to argue the toss over the validity of the try. These 51-49 decisions are deliberated over assiduously by match officials, often to the detriment of the game’s natural rhythm. Indeed, it was two hours and 13 minutes before the whistle was blown on the second Test, with numerous TMO referrals, and the fans were quick to voice their displeasure of the game as a spectacle.

But what if technology was able to offer a decision, based on scientifically-proved data, within milliseconds, thus proving or disproving a contentious judgment and speeding up the game in the process.

As luck would have it, help is at hand from two South Africans with the intellectual curiosity and intelligence to change the game and haul it into the 21st Century.

Dugald Macdonald and Pete Husemeyer were born two days apart in the same hospital in Johannesburg. They went to school together and studied at the same university in Cape Town. Both men then travelled to the UK to finish their post-graduate degrees, with Macdonald at Oxford and Husemeyer at Cambridge.

Macdonald has a rich rugby pedigree. He followed his father, uncles and brother in playing for the Blues while studying finance. Pertinent to this summer’s action, his father played his first, and only, game for the Springboks against the ‘74 British & Irish Lions in the second Test in Pretoria, while his uncle, Donald Macdonald, a lock, played for Scotland.

Husemeyer’s lineage isn’t storied in rugby tradition, but in chess and engineering. After a PhD at Cambridge, he moved into nuclear engineering, before moving into the US space industry with NASA, helping power deep space probes and using nuclear as a propulsion mechanism for rockets. US Congress awarded the South African for his work and his optimisation code is still used and is called Spock, after the iconic Star Trek character.

It was while he was working in America that Husemeyer had an epiphany. “With NASA, I travelled a lot. I was in Louisiana, Alabama, New Mexico and Arizona and watched a lot of sport. One sleepy evening in Idaho, I was watching an ice-hockey game and saw two guys collide on the ice. It got me thinking, ‘Why is there no data about the impact?’ For me, it lit a fuse,” he says. “I came back to London and told Dugald about the genesis of my idea. He immediately saw the commercial possibilities and phoned me within 24 hours and said, ‘We’re starting a business’. Sportable was born.”

We started to see there was a thirst for data at every level; broadcasting, betting, fantasy sports and of course the actual game on the field. These are competitive environments in which reliable data is often the difference between winning and losing.

Dugald Macdonald

Macdonald says his interest was piqued because he saw it as a defining feature missing from the sport he loved. “Pete’s idea really captivated my imagination. Think about what is delivered to us data-wise in tennis or cricket, or Formula One for 25 years. Rugby currently lacks that objective insight, in terms of being able to educate the fan into what was happening on the pitch,” he says.

“From that moment, we started on a journey of discovery to look at the sport from a content and data perspective. We started to see there was a thirst for data at every level; broadcasting, betting, fantasy sports and of course the actual game on the field. These are competitive environments in which reliable data is often the difference between winning and losing.”

Assisting Macdonald and Husemeyer is Giles Morgan, the former HSBC head of sponsorship, who has a whip-smart understanding of rugby’s commercial opportunities.

With close to £750million of private equity money swilling around the professional game in the northern hemisphere, and more looking likely to be added in the southern hemisphere, he acutely understands the necessity for change.

“I think rugby is facing an existential moment in its development right now particularly when you look at private equity piling into the sport. We know they will be looking for a return, even if it’s over a 10-12 year period. For a sport to keep its value, you have to keep the fans engaged or face becoming moribund. Rugby has, in a sense, traditionally delivered the right audience but as the Lions tour showed, it’s only attractive financially if it’s attractive to fans,” says Morgan.

With tech-savvy digital natives, spearheaded by Generation Z, there is an acceptance younger audiences consume media in a different way, says Macdonald. “They play FIFA, or Madden on gaming devices and if your live experience doesn’t marry up with your virtual experience, then you’re going to have a hard time connecting with emerging audiences. Intuitive data from the game is always going to be helpful in educating and connecting the fan at a youth level,” he adds.

So what can Sportable, as a fledgling start-up, do to help rugby, given the majority of sports still rely on game facts collated by humans? “Take the OPTAs of this world. People are tapping out rucks hit or tackle counts on a keyboard. If you look at any of those stats, almost none of them have a bearing on who wins the game,” says Macdonald.

“Then we have the subjective element voiced by the commentators on the side of the field. It has value but is not creating an objective frame of reference for the fan. It’s not that rugby is in the dark ages, any coach or high-performance sports scientist in the game is a potential target for a team in the NFL or AFL, but they don’t have the optimum tools at their disposal because existing technology has hit a ceiling. Human data input can only tell you so much or move so fast to relay information.”

Of course for the eagle-eyed among the sports audience, you have camera tracking like Hawk-Eye, but it doesn’t work so well in contact sports, Husemeyer says. “GPS is worn by every single player that is great for telling us distances run, acceleration and athleticism but it’s not going to tell us about the tactics or decision-making. It won’t unlock the hidden source code to the narrative of the game,” he adds.

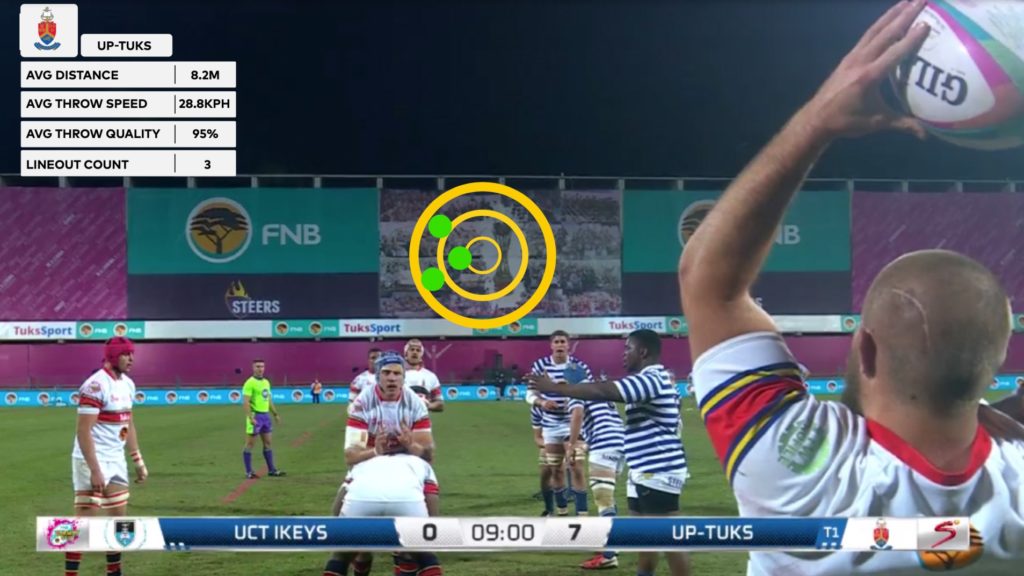

From a Sportable perspective, that’s where they claim they can help. “Our team have created sensors and software. The sensors pull the data and the software tells the stories by curating them into meaningful insights,” says Macdonald. This is where the science comes in, according to Macdonald. “If we take a 10,000ft view of rugby, what are its pillars? Well, first and most important is the ball. The conductor of the orchestra, if you like. The tactical off-the-ball movement, that’s all happening in terms of where the ball is, or where it’s going to be. Whether they’re kicking it, passing it or throwing it in as the lineout, a player manipulates that ball. That defines how good they are technically and it’s what clubs pay players to do.”

We want your son or daughter to be talking about the rugby data, not the NFL or NBA, which is where so many young eyes are veering these days.

Macdonald argues that if we’re not tracking and analysing the ball we are doing our jobs with one arm tied behind our back. “We have invented a tiny tracking chip that is embedded in the ball which measures the hang time, speed, distance and even the spin rate. We want to get the perfect balance of weight and flight dynamics, so we’ve hooked up with two of the biggest rugby ball manufacturers in the world, Gilbert and Steeden, to make sure the ball meets the requirements of the game’s elite players,” he says.

The second pillar is player movement, according to Husemeyer. “We need to be able to understand player work-rate and behaviour in terms of each other and the opposition so we can track them to centimetre level accuracy. Our software knows who’s holding the ball, who has passed it and who has kicked it. It even knows what type of kick it is,” he says.

Macdonald says the final piece is a wearable that can determine the forces in scrums and tackles, something that will be of particular interest to coaches: “We can tell how hard people are pushing in the scrum, how synchronised it is, if the tighthead and the loosehead are hitting at the same time. We want to tell rugby audiences how good players are at kicking, passing and throwing. How good teams are at executing off the ball strategies and we want to help officials make better decisions in terms of refereeing.”

Such is the excitement around the technology that Sportable believe they can detect a forward pass or offsides in real-time. “We want your son or daughter to be talking about the rugby data, not the NFL or NBA, which is where so many young eyes are veering these days,” says Macdonald.

Macdonald says the software, which tracks the ball in real time and in 3D, has limitless opportunities for analysing the game: “Take the kick-off. The most important variable is hang time. In real time, AI (artificial intelligence) will track the kick, see what type of kick it is and then send through the data so we have a frame of reference, using in-game visualisation tools. Let’s say who has the highest hang time, Owen Farrell or Handré Pollard, and how has it affected the game? When it becomes truly powerful is when we start factoring in objective insight. For example, if you get to the 75th minute of the game and the trailing team have a kick-off, the data can categorically tell us that whether we can rely on a player to put the ball on a dime, so a commentator can come in and ask his summariser, ‘This is what is was like playing with Owen. I could pin my head back and run to that spot and I’d know it would be there. It’s analogue and digital technology working in tandem if you like.”

We can tell if it’s a forward pass in three-tenths of a second, or even faster. The instant a ball leaves a player’s hand we can provide the referee with a heads-up. I have to say we are categorically not trying to replace the referee. We are trying to make their job easier.

Pete Husemeyer

With officiating under the microscope, especially in the wake of Rassie Erasmus’s infamous video response to the first Lions Test, the data can help eradicate interpretation, with forward-pass technology launching in Australia later this year. “Our technology can actually tell you where the ball went out into touch. We tracked the touch judges in a number tournaments and there was 5 1/2m error. That’s sizeable when every inch counts. We want to improve accuracy and keep the game flowing,” says Husemeyer.

Husemeyer says that while they respect current technology such as Hawk-Eye and admits it is a company they are trying to replicate, it does have its deficiencies: “When you’re using Computer Vision, you’re searching through millions and millions of pixels at 36 frames per second and working with high-end servers. That can take a while to come up with a conclusion. In that time, the team have scored a goal and fans have celebrated, so it’s not good for the sport. We have focused on speed, so with our technology we have factored in six million fewer calculations to come up with a result. As a consequence, we can tell if it’s a forward pass in three-tenths of a second, or even faster. The instant a ball leaves a player’s hand we can provide the referee with a heads-up. I have to say we are categorically not trying to replace the referee. We are trying to make their job easier.”

For Morgan, he feels there is simply too much at stake for the power to be given back to the referee because the technology of images takes too long and the fans are left waiting and frustrated. “This is top-level sport. It is only fair that the correct decisions are made and that they’re made instantaneously. It is an enhanced fan experience which gives veracity. We need that in rugby because as we saw in the Lions series, there was a toxic edge to discourse by fans on social media. That isn’t rugby or in the spirit of the game we love,” he says.

For the sponsorship expert, he acknowledges, rugby can ill-afford to stagnate and needs to look forward: “The next generation are consuming sport differently. They want it bite-sized and they want faster. They want technology blended into the reality. That is something that is natural to this generation. The sports that are going forward in the 21st Century have embraced the digital advancements while preserving their sense of self.”

No sport has a divine right to remain viable. Rugby has to shape itself by its fan experience and to do that means creating a game that flows quicker and better for this generation and the next.

Giles Morgan

Overt professionalism is anathema to rugby’s traditionalists, but it is something that cannot be ignored in the 21st Century, he believes. “One of the checkpoints for rugby is that it is a very attractive demographic. Make no mistake, that’s why private equity has gone into rugby. It isn’t the sport, it’s the audience, but the audience will only remain switched on if the sport continues to turn them on and to do that you have to embrace the next generation,” says Morgan.

“My son is 18 and part of the Fortnite generation. The way he watches sport is different. There are a litany of sports that didn’t make it. I mean, who watches jousting any more? No sport has a divine right to remain viable. Rugby has to shape itself by its fan experience and to do that means creating a game that flows quicker and for this generation and the next. This isn’t throwing the baby out of the bath water, or reinventing the sport, it’s taking the technology that is available to actually simplify the game.”

Having been involved in sponsorship with HSBC and now Aberdeen Standard Life, Morgan knows rugby ticks so many boxes to big corporations because of its tradition and heritage but if you fast-forward that 20 years and it hasn’t kept up with an audience it will no longer be attractive. “Whilst people may decry it and say, ‘It’s all about money’, I say, ‘Yes, it should be, but for the good of the game’. It should be a virtuous circle,” he says.

“You need stadiums to be upkept, players getting paid well and tours to keep going. I’ve been in the game for a long time and it could present a new chapter for this sport. I genuinely mean that. Rugby is on a pivot point and simply has to take the right pathway.”

More stories from Owain Jones

If you’ve enjoyed this article, please share it with friends or on social media. We rely solely on new subscribers to fund high-quality journalism and appreciate you sharing this so we can continue to grow, produce more quality content and support our writers.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free