We all know Finn Russell is down for a bit of risk, but the riskiest thing you can do in his presence is underestimate him. ‘Who’s underestimating him?’ I hear you ask. Well, no one doubts his world-class running, passing and offloading game. But the occasional cries that he doesn’t have the temperament to manage a Test match under pressure are enough to plant an element of doubt in our minds. He has the chance to change perceptions this weekend as the Lions take on their namesake, the Emirates Lions.

I’m not going to pretend starting Russell isn’t a bit of a risk – the man loves going for ballsy plays, sending speculative kicks, throwing passes that linger dangerously into interception territory and he sometimes gets his tackle technique slightly wrong.

That said, Russell’s flashy, nature should not detract from his remarkable ability to manage a game. If defenders knew he was going to do something silky every time he got the ball, he would become predictable. Let’s have a look at how the more simple aspects of Russell’s game allow him to go for these outrageous plays.

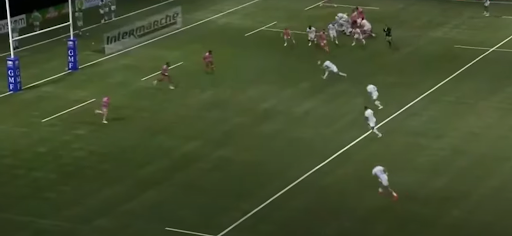

This first example is for Racing 92 against Stade Français. This is from the first phase of a scrum on the right-hand side of the field.

Stade have two men in the sin-bin, so they play this set with a seven-man scrum and a six-man backline. They opt for a drift defence, with scrum-half James Hall dropping from the back of the scrum into the defensive line in order to aid fly-half Joris Segonds.

With a player advantage, Russell resists the temptation to go wide on first phase, knowing that would realistically lead to a cover tackle and subsequently the forwards attempting to drive over themselves. Instead, Russell attacks the hole between the two Stade half-backs, opening up a soft shoulder for centre Gael Fickou to run at.

Fickou runs straight and gets a dominant carry. He eventually carries unders, towards the Stade traffic, preventing them from folding round quickly. This opens up a huge open side for Russell to attack. Russell immediately gets back into the first-receiver position for the next phase and calls for the ball again.

On this 4v3 overlap, it’s not the numerical advantage that matters, but instead the width they have set. The final two Stade defenders have to actively mark large spaces either side of them and full-back Kylan Hamdaoui turns his hips inwards to cover the inside space. This means Russell would typically have to throw a speculative ball over the top to Donovan Taofifénua, allowing Hamdaoui the time to turn and cover him while the ball is in the air.

Russell, however, places the ball in the space just outside Hamdaoui to tempt him into the intercept. This is a surprisingly low-risk play – the full-back is at full stretch and unlikely to take the intercept and, even if he does, he risks knocking the ball on, slipping over or not being able to get away from the Racing cover defence in time. This worldie of a pass by Russell is made within a second of him receiving the ball.

The pass also pulls Hamdaoui away from try-scorer Simon Zebo, who is running an overs line on to the ball. Instead of passing to Taofifénua, who was in more space than Zebo, Russell made the correct choice of manipulating the wide defender and setting both of his outside men away. If a Stade defender miraculously managed to catch Zebo, he still would have been in a good position to offload to his winger.

The simpler decision of Russell to hit Fickou on the short ball not only generated quick ball but also prompted the Stade defence to mark the simpler options around the fly-half as opposed to the miracle ball.

This principle does, though, work both ways. The minute you set up to defend one of these insane, one-of-a-kind plays, Russell will punish your backfield. Fans are often quick to assume Russell is merely a running No10, but in this year’s Six Nations he notched up more kicking metres than any other Home Nations player.

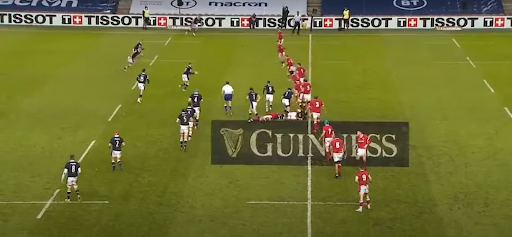

The following example is an excellent decision and kick by Russell, from Scotland’s opening game of the Six Nations against England.

This Scotland possession comes as a result of an English 22 drop-out. After kicking, Owen Farrell covers the backfield on the left-hand side, allowing winger Jonny May to chase hard.

Russell strikes a high bomb into the air, aiming for it to come down on Farrell. Russell immediately drops to cover the backfield with Stuart Hogg. While Farrell is usually good under the high ball, the Scotsman backs his winger Sean Maitland, who has played internationally at full-back, to have better technique in the air than the English fly-half/centre.

The kick is perfectly placed – it’s just outside the England 22 so Farrell can’t call a mark and if he does catch it, he is most likely getting tackled straight away, allowing Scotland plenty of time to form a strong line. Additionally, Farrell is not recognised as one of England’s strongest counter-attackers – if it was Anthony Watson or Elliot Daly he was kicking to, Russell may have been slightly more cautious. Instead, he trusts that Maitland would get a good tackle on Farrell if necessary.

Maitland rises above his Saracens team-mate to win the ball and bats it back to Matt Fagerson. On the following phase, Russell organises a convincing screen of forwards in front of him and works the ball wide for Duhan van der Merwe to score.

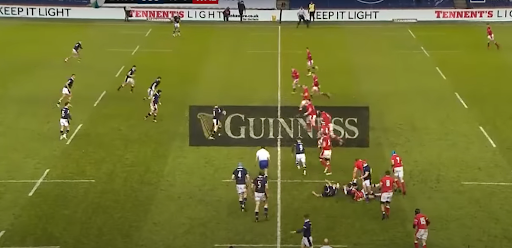

Now that we’ve seen him penetrating a defensive line and placing punishing punts in the air, let’s have a look at Russell’s territorial kicking for touch. This next example is from the Scotland game against Wales the following week.

The trend in the first half of this match was for Scotland’s forwards to play off 10. Russell hits Gary Graham on a short ball and attacks the same side on the next phase. Wales do well to fold around, but Russell remains flat to the line.

Russell remains flat, with no indication that he is going to kick. He spots that winger Louis Rees-Zammit has come into the front line, with his back-three compadres organising the backfield.

Russell proceeds to kick the ball along the floor. Given the close proximity between him and the Welsh defensive line, any pressure on a right-footed kicker could lead to him slicing the kick and the ball going out on the full. By keeping the ball low, Russell minimises the possibility of this, making sure the ball not only bounces early, but travels fast and is therefore harder to catch on the full.

Wales full-back Liam Williams, who is still travelling across to cover the space previously occupied by Rees-Zammit, has no real choice but to let the ball roll into touch here. He has the titanic Van der Merwe breathing down his neck, so fielding the ball would require him turning and likely having no room to kick or sidestep. The ball rolls into touch for a Wales throw inside their own 22.

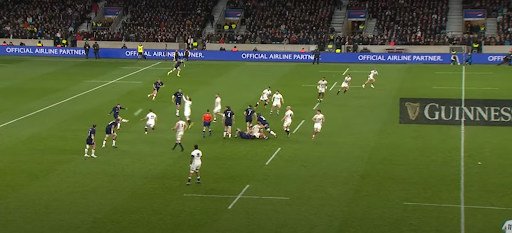

Let’s look at one more example of Russell making a mockery of a top-class winger, this time in the final round of the 2019 Six Nations against England – in which Russell orchestrated a 31-point comeback and won man of the match.

With three minutes to go and Scotland seven points up, Russell strips Ellis Genge, leading to a Sam Johnson carry. Russell sits in the pocket, just outside of his own 22, and England expect the fly-half to put as much distance on the ball as possible and kick straight down the throat of Daly, so Jack Nowell remains in the front line.

Never make assumptions about Finn. Naturally, the fly-half looks for space.

While this kick isn’t contestable, it’s placed perfectly between Nowell and Daly. Nowell is constantly backpedalling and unable to find his bearings. Given Nowell is usually technically spot on under the high ball, Russell finds a lot of grass behind him. The ball rolls into touch five metres out from the English tryline.

Much like running and passing, Russell loves to kick while on the front foot. If his team are going backwards, looking to exit or wanting to slow the game down, he is much more likely to utilise Ali Price or Stuart Hogg, but his kicking strategy is all down to manipulating defenders and finding space.

Once he has plenty of other options, teams can’t sit back and expect him to kick. He may not have the cannon-like boot of Dan Biggar or Handré Pollard, but his awareness of space buys his chasers equal amounts of time to truly punish an opposition backfield. For a man who is no stranger to messing about on a rugby pitch, the Racing star is ultimately capable of pulling out match-winning plays.

More analysis from Will Owen

If you’ve enjoyed this article, please share it with friends or on social media. We rely solely on new subscribers to fund high-quality journalism and appreciate you sharing this so we can continue to grow, produce more quality content and support our writers.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free