Speaking on the radio while a Celtic Cup match between the then titled Llanelli Scarlets and Newport Gwent Dragons was being shown on TV in front of him, the comedian and broadcaster Owen Money said he had just seen a spectator walk 50 yards inside the ground to get a light from the bloke alongside him.

It is not new for Welsh rugby to have problems.

Back then, in those early days of the regional game, attendances were one of the things causing concern, with the newly branded entities all finding it a challenge to grow their support bases. Indeed, the Celtic Warriors attracted gates of just 1,500 twice during the campaign. Team numbers, too, were an issue, with the Warriors finding themselves wiped off the rugby map after just a season as the Welsh game cut to just four professional sides in an attempt to thicken the layers of finance and talent at each region.

Fast-forward a decade or so and the then Ospreys chief executive Andrew Hore was confessing to being “pretty concerned about where we are at”.

He continued: “There are all kinds of problems that need urgent attention.

“The way I see it, Welsh rugby as it stands is a burning platform and if we let it blaze the consequences don’t bear thinking about.”

For Hore, the burning platform covered low player numbers, the threat posed by football, the lack of a commercialised outlook, the strong commercialisation of the game outside Wales allied to big TV deals, issues with the Welsh game’s governance and structure and Welsh players being targeted by clubs with bigger budgets.

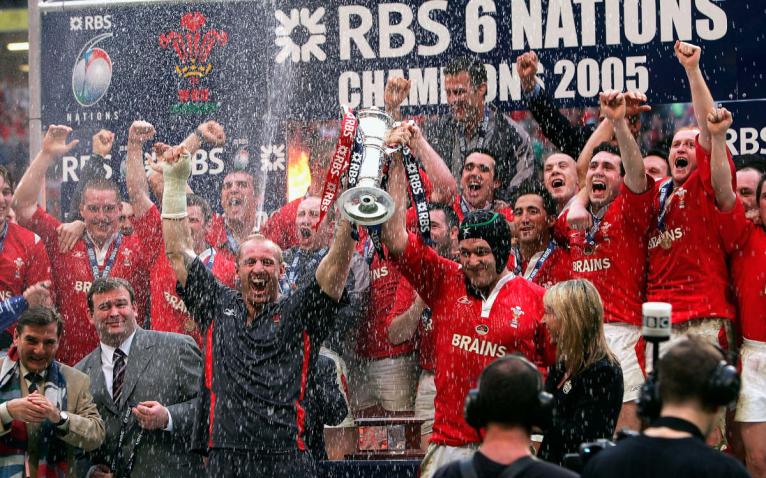

He went out of his way to stress the seriousness of the situation, saying: “We don’t want to be sitting here in 10 years’ time viewing some of our recent national teams as we view sides from the 1970s, as part of a successful era that stopped abruptly and left a big gap between where they were and where we ended up – in the 80s and 90s there was a gap that proved disastrous.”

It is close on a decade since he spoke, and, lo and behold, we are sitting here reflecting on a successful era that came to a halt. Changes are belatedly being made to the Welsh game’s governance and structure, but bad news still seems to rear its head every week, if not every day.

The question for the Welsh Rugby Union is not just whether Wales have gone backwards but why such regression has happened. Is the coaching not what it should be, or are the problems more deep-rooted?

This week alone, the last region standing in Europe, the Ospreys, were eliminated from the Challenge Cup after an off-key performance against Gloucester at Kingsholm, while the following day Wales Women were crushed 36-5 by Ireland, who avenged a 31-5 beating in Cardiff a year earlier. Optimism around Ioan Cunningham’s team has evaporated, with the coach under scrutiny as his side play out their Six Nations campaign. Rival sides have improved, but the question for the Welsh Rugby Union is not just whether Wales have gone backwards but why such regression has happened. Is the coaching not what it should be, or are the problems more deep-rooted?

The Ospreys deserve credit for defying acutely unfavourable circumstances in respect of finance to qualify for a European quarter-final, but they didn’t do themselves justice in front of The Shed. They lacked forward ball carriers and were uncharacteristically suspect at scrum and lineout. Their wing Keelan Giles looked dangerous, scoring a well-taken try and beating seven defenders, while the centres Keiran Williams and Owen Watkin ran hard, utility back Jack Walsh was the most creative player on the field and Justin Tipuric and Morgan Morris grafted tirelessly, but the Welsh team could have done with Rhys Davies at the heart of their pack and found it hard to shackle the powerful Ruan Ackermann and his back-row colleague Zach Mercer, who combines cleverness with skill and a high workrate.

Toby Booth’s side were also without the Wales pair Jac Morgan and Dewi Lake, as well as George North and Alex Cuthbert. With his ability to plough through tackles, Lake was particularly missed during a game that saw just two Ospreys forwards, the aforementioned Tipuric and Morris, return double figures in terms of carrying metres.

Williams is an interesting player. His effort in Gloucester attracted what might be termed mixed reviews, but he made 11 tackles and put in the same number of carries, along the way beating four defenders. Manny Feyi-Waboso has shown this season how impactful a three-quarter who channels every ounce of power into a relatively small frame can be. Wales have shown no interest in Williams since capping him in a friendly last year, but he is an individual worth keeping tabs on.

Just three months ago, WRU chairman Richard Keywood-Collier admitted there had been no formal talks about an Anglo-Welsh competition getting off the ground.

Back to the problems, or rather let’s have a look at the putative solution to many of the ills, namely an Anglo-Welsh league. There can be few in Wales who wouldn’t like to see such a development. It would, after all, revive the idea of away supporters for games where the opposition are non-Welsh at regional grounds. It would make travelling easier for followers of the Welsh teams. Traditional Anglo-Welsh rivalries would be renewed. Interest in Wales would potentially swell, attendances would likely rise. It would give the Welsh game a shot in the arm.

But, sadly, such a scenario seems as far away as ever. Indeed, just three months ago, WRU chairman Richard Keywood-Collier admitted there had been no formal talks about an Anglo-Welsh competition getting off the ground. “Our position is we are committed to the United Rugby Championship (URC),” he said.

“There are dates we are committed to and we will have a good look at what the future options are.

“It is not straightforward to switch and we’re doing our best to make sure the URC is commercially attractive. The URC is in place and England have their own commitments.”

We can’t even be certain there is great enthusiasm for an Anglo-Welsh competition in England. The 9,816 attendance for the Gloucester-Ospreys game was respectable, but the Cherry and Whites are averaging more than 13,500 for home league matches this term. And when Cardiff played Newcastle Falcons at Kingston Park last season, they did so in front of only 2,667 spectators, the English club’s lowest gate of the campaign for a league or European match.

The England-Wales dimension might provide extra spice, but it’s far from certain the financially challenged Welsh sides have the appeal they used to have.

When rugby was considering going professional, the then Wales coach Alan Davies warned that there were more millionaires in Harlequins rugby club than in the whole of Wales.

In the absence of a radical shift in thinking on the competition front, then, it may be that Welsh rugby will just have to make the best of the hand it currently holds. As a bare minimum, that means the WRU governing with vision and insight, doing all it can to make the sport in Wales attractive to the next generation, shining up its commercial potential and investing in the professional teams and in development. It also needs to find a way to adequately fund the women’s game while making sure the grass roots are nurtured.

All of which costs, of course, but that shouldn’t be breaking news.

When rugby was considering going professional, the then Wales coach Alan Davies warned that there were more millionaires in Harlequins rugby club than in the whole of Wales. Since then, it seems to have been a never-ending tale of too little money for the sport this side of the River Severn, too many mouths to feed. A hundred years from now, doubtless the same problems will still be with us, with Midas continuing to give the Welsh game a wide berth.

Like Dickens’ Mr Micawber, maybe we can but hope something will turn up.

But, really, there needs to be a better way.

Answers on a postcard, please, directed to the WRU and all who run the governing body.

We will always struggle for money to match the other sides but the least the WRU can do is invest properly in Welsh rugby.

Too much has been squandered on vanity projects like the hotel and roof walk amongst others which will never see a massive return.

Hanging the 4 pro sides out to dry over the last decade is now coming back to bite the WRU financially as well as on the pitch.

You reap what you sow.