A single glance at the Gallagher Premiership is enough to tell you professional rugby is getting faster and providing more entertainment value than ever before. Ball-in-play time is rising steadily towards the 40-minute watermark, and several high-profile games have exceeded that threshold.

The much-touted ‘Grand Slam decider’ between Ireland and France in February 2023 ended in a 32-19 win for the men in green and contained over 46 minutes of ball-in-play, which was probably a record at the time. The figures suggest the game is on the right track (I am indebted to Rhys Jones and Corris Thomas at World Rugby for many of the following statistics).

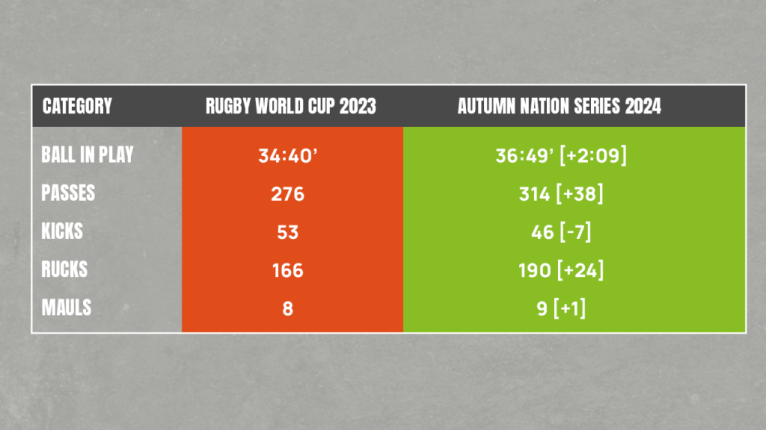

Twelve months have been enough to generate a two-minute increase in ball-in-play time, and encourage more passing and less kicking than ever before. World Rugby has been actively looking to create even more content by passing the four-point 2024 trials into law proper at the beginning of the New Year:

- “Sixty-second conversion limit to align with penalties and improve game pace. This will be managed by a shot clock where possible.

- Thirty-second setup for lineouts will match time for scrums to reduce downtime. This will be managed on-field by the match officials

- Play-on in uncontested lineouts when the throw is not straight.

- Scrum-half protection during scrums, rucks, and mauls.”

Shot-clock management with shorter windows for the kick at goal, quicker set-up for the set-piece; ‘play-on’ for uncontested lineout throws, and greater protection for the acting scrum-half looking to move the ball away from scrum, ruck or maul are all sensible streams of improvement in the content rugby offers.

According to the research undertaken by Rhys and Corris, the 60-second goalkicking limit by itself saved an average of anywhere between 11 and 22 seconds per kick in the two competitions in which they were trialled [2024 Rugby Championship and the subsequent Autumn Nations Series]. In a high-scoring match such as the 10-try fiesta between England and Australia at Twickenham, that could add as many as three extra minutes of active time to the game.

The law amendment governing the removal of ‘escort running’ – defending players ahead of a high kick shielding the receiver – also had a positive impact on ball-in-play time, with the proportion of contestable or attacking kicks rising by 15% from the World Cup to the ANS. Contestable or attacking kicks such as grubbers or chips are by their nature designed to stay infield rather than go out of play.

So far, so good. If there is a nagging bugbear, it is the scrum – one area which still obstinately to refuses to move with more fluid and progressive times. There were some slivers of light in the Rugby Championship, where scrums with stoppages saved an average of 22 seconds compared to those involving no stoppage at all. The problems tend to arise when at least one of the teams is determined to scrum for penalties and actively seeks their reward from the referee’s whistle.

In those circumstances, there tend to be more resets and more penalties given, which suits the scrum-focused team and has the practical effect of backing the referee into a corner. When the on-field official becomes aware time is leaking away via resets, they are more likely to award a penalty or free-kick to resolve the deadlock.

An excellent example of both the positives and the negatives occurred in the derby match between Irish rivals Munster and Leinster in the United Rugby Championship just after Christmas. The ball-in-play time was average at just over 36 minutes, and the two teams between them set 200 rucks, which is well above it. All five successful goal kicks in the game were a conversion of tries scored, and came in anywhere between 10 and 30 seconds under the allotted limit of 60 seconds per kick. No fewer than 14 kickable goals were refused, with both sides opting to take lineouts deep inside the opponent’s 22m zone rather than attempting the three-pointer.

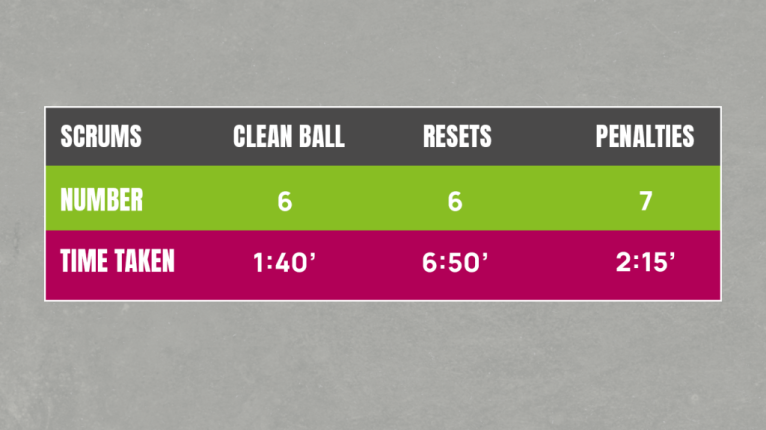

The interstate derby was played closer to source than usual, bearing comparison with a knockout round of the World Cup; and if there was one area of the game which took away from, rather than added to, the overall spectacle for a potential newcomer to the game, it was the scrum. There were 18 scrums put down in total, and the time used up was 10 minutes and 45 seconds – or 13% of total game time.

The issue, for attracting new fans and ‘putting bums on seats’, derives from the scrum outcomes.

Only one third of the scrums set produced clean ball, the rest resulted in either another scrum or a penalty. More than 60% of the time taken occurred when scrums were being reset with the clock still ‘on’, with the clean ball and penalties won only taking an average of 17-18 seconds to resolve.

Penalties from scrums won anywhere in the opponent’s half of the field morphed into attacking lineouts in the red zone, raising questions about the point of staging the set-piece in the first place. Four of the six resets occurred in the first half but the majority of penalties were awarded in the second, hinting at just how early pressure is created in the referee’s mind – to shape perceptions and force them to make decisions later in the game.

In recent times, Leinster have been known more for the quality of their moves off scrum but under the tutelage of Springbok World Cup-winner Jacques Nienaber they have tended to scrum for penalties far more regularly, and at Thomond Park the men in blue won six of the seven penalties awarded by referee Sam Grove-White. Leinster’s set-piece was unquestionably the stronger of the two but the primary question is: should the reward for a stronger scrum come from penalties, or greater attacking opportunity with the ball played out?

The process of creating pressure via resets started at the very first set-piece.

Keyed by ex-Clermont and France tighthead Rabah Slimani, the Leinster scrum moves forwards and sideways a few inches before popping up in the middle. There are at least three clear technical offences on view: Slimani steps right rather than moving forward, his hooker Ronan Kelleher is the first to pull his head out of the contest, and Munster flanker Thomas Ahern slips his bind to slide up and baulk Slimani.

Although the reset was completed, Leinster received their first penalty reward at the next set-piece.

At the first attempt, Slimani takes a step inside rather than out, his opponent Dian Bleuler drops to his knees, Kelleher pops up and Ahern breaks his bind to make a fourth prop. A penalty is then awarded at the reset as the scrum does little more than spin around Munster tight-head Oli Jager and disintegrate.

Leinster promptly converted the opportunity by kicking to the corner for a 5m lineout and scoring a try from short-range. But was the ‘punishment’ equal to the ‘offence’ in the first place? Probably not. Three simple solutions are already possible.

- Create an easy ‘time-saver’ by having the clock stop automatically when the ref calls ’reset’ and start up again only on the following ‘crouch’ command? No time is wasted, no pressure can be built on the referee’s decision-making and the official can relax into their work.

- Make the ball more playable by requiring the defensive scrum-half to retire immediately behind the hindmost foot of the scrum. This was already an important part of the law-trial ‘protecting the 9’ at the 2024 Rugby Championship.

- Allow the ball to be picked up by any member of the feeding back-row, including the near-side flanker [Ahern] in this instance.

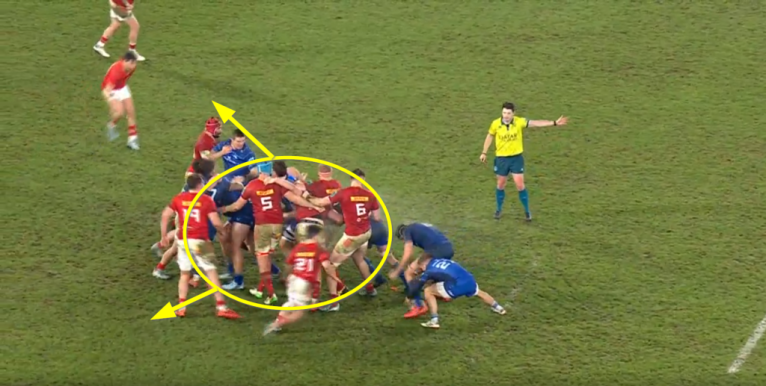

Leinster pulled off the same trick twice more in the first period, building pressure and shaping refereeing perception via a reset and then cashing out with a technical penalty. The final example came in the 56th minute.

The first scrum rotates on the spot, and at the second Grove-White feels compelled to award a penalty against Jager for a slight inward angle. The offence is innocuous at best and the ball is already available to be played away at the back of the Leinster scrum in any case. Play on.

There was still time for one instructive final scrum towards the end of proceedings.

This is a genuinely dominant scrum by the men in blue, moving forward at a rate of knots on both sides simultaneously, but it still does not need to finish with a penalty. If the defensive nine is required to retire behind the hindmost foot, and all the Munster forwards within the orb to retreat behind an offside line established by the most advanced Leinster forward, the cards are stacked in favour of the attacking side when the ball is moved out.

World Rugby has made great strides in increasing the volume of content in a game of professional rugby in recent times, even in a short window of 13 months since the 2023 World Cup. More ball-in-play time, more passing and infield kicking, shorter intervals for goal kicks, quicker set-up at set-piece are all valuable changes.

The scrum remains an issue as a time-loser on resets, and as the more ‘negative’ of two set-pieces: all too regularly used as platform to win penalties and create attacks off its cousin, the lineout. Establishing a new offside line for the defensive nine and retreating forwards, and stopping the clock automatically for resets, will encourage more ball use and positive attacking play. At scrum-time, the best is yet to come.

By adding the word physical the only logical conclusion I could make was to ensue you were excluding factors like technique and skill from having equal parts the 'contest'.

If it was a redundant word then yes, I fully agree that it's half the game. But I then don't think it can be used to validate any other parts of your argument.

So in conclusion I think it shows you don't have a rounded view of what rugby is. Your interest is better suited to a game like League.

Well JW they are not exactly competing in chess or Trivial Pursuit. What other sort of competition other than physical can take place in a rugby game.

That's disappointing Graham. Were just talking about what we want, theres no front or back foot mate. Why are you shying away now?

You really don't make sense when you argue off the back foot.

Well refs did try it a while back and it was considered too dangerous, so they had to allow some bias on the feed. I can't see how we'll ever cycle back to those days.

The issue is all around eating up time. there are some interesting suggestions here. One that I have been thinking about is basically a "clock time" limit for a scrum. Once it is awarded, no matter how many resets there are, the match clock only moves ahead for a limited time (90 seconds?) I love the scrum as part of our great game and would hate to see it devalued further.

One other wee aside; I am not sure that the scrum halves needed that extra protection. There is a skill set to challenging your opposite number and this change may actually change the type of athlete in demand in this position. I would not like to see that.

I remember now, and you have to agree until they can check the power, via substitute restrictions and having more ball movement etc.

Actually, the scrum really needs something like the 'hook' back in it again, if we forget for an instance that hooking the ball creates a disadvantage to the team whos supposedly supposed be given the advantage, could the ability to safely 'hook' the ball again be a good indication of a balanced and safe scrum in general? As in, start adapting/changing laws till everyone doesn't collapse on their face when the hooker lifts his leg (I pointed this was the cause of some collapsed scrum to youo in the past) a fraction.

You're only watching it with one eye open G.

Look at Vincent Koch's angle, he's scrumming straight towards the far sideline from the set.

If we're going to get technical that was the first offence, though none worth a pen in that scrum.

Watch it again Nick. I just did five times the English front row went sidewards under pressure then stood up. Their front row disintegrated. Agree with your saying the scrum penalty is generally a lottery but that's not a good example of that point.

I think it comes down to creating incentives JW.

If you create enough clear attacking incentives from a dominant scrum they will override the desire to win pens, and we'll see more ball being used to attack!

They tried it briefly after Biran Moore's suggestion a few years ago, buth then said that the pressures of a modern scrum were too great for the ball to be put in straight down the middle - too much danger for the hooker having to raise his foot and hook the ball back on one leg!

Bottom line is that there is no way to speed the scrum up. You speed up other aspects of the game but the scrum is sacrosanct and takes as long as it needs to take. If people don’t like it then remove it entirely or let it be. The day the scrum is removed or turned into a non contest / uncontested farce is the day I stop watching rugby.

Nah, it can certainly be speed up (it has been as a fact). Like with kickers, they would take forever if they were allowed to.

But speeding them up further is not the answer (no one has suggested it as a solution so not sure why were talking abuot?) to anything, no, it is about player safety now. Results will be made by increasing their success rate. And you make a very good point that it is all about balance anyway.

It won't be rugby at that point DP, so nobody will be watching rugby! A sobering thought everyone at WR should keep in mind.

If anything Nick, I hope you’re taking some notes to improve or enrich your pending article I assume to be titled:

“It’s not fair, waa, waa. Scrums and other things that need to be changed to suit the North”.

😆

Far from it. Teams in the north, and esp in France, probably scrum for pens more than anyone else outside the Boks.

Why is it so damaging to ask for scrums to produce a majority of usable ball, not pens. Isn't that what they were originally designed for?

If one side can overwhelm the other and go forward, all well and good. Use that ball to attack unless there is an obvious offence by the weaker side.