When Franco Smith’s name was first bandied around the Glasgow changing room in the summer of 2022, Simon Berghan took out his phone and loaded up Google. He scrolled through what, on the face of it, looked a sound if not exactly blockbuster coaching CV. Two Currie Cup titles at the Cheetahs, stints with an unfancied Benetton side and the perennially win-shy Italian national team.

Friends in the game spoke of Smith’s love of running and, in his early days, autocratic tendencies. His disdain for flip-flops at the Cheetahs was mentioned, and players joked about whether their Birkenstock shoes would still be allowed at Scotstoun.

Glasgow had champion credentials – a team full of Test regulars and burgeoning tyros who longed to cross the barrier from contenders to winners. They’d ended the previous season with a quarter-final savaging at the RDS which cost Danny Wilson his job and raised confronting questions within the environment.

To Berghan, Smith was an unknown. Whatever his arrival meant, the prop was ready to embrace the change.

“We wondered what we were going to see from him. Somehow Franco heard through the grapevine that [banning flip-flops] was a conversation before he arrived. He actually addressed it. He said, ‘listen, that was the old me, I don’t care what you wear on your feet’.

“We quickly met his wife and family. He was really big on that, a big advocate of any event, coffee mornings where half the team bring in cake and all the families come. That stuff sounds really cliched but it’s a game-changer. To have your head coach with his wife, really engaged, was big, particularly for me as I find that stuff really important.”

Within months, Smith’s family-centric approach was embedded in Glasgow’s culture. Berghan was competing in drop-goal competitions with the one-time Springbok playmaker at training. He watched Smith weep in meetings when team-mates would share their stories of hardship and struggle. He was enthused by the progressive yet unrelenting style set out for the players, underpinned by brutally high standards of fitness and skills, and an unwavering belief in the masterplan.

This was the road which took Glasgow to unthinkable heights, the brain behind the greatest result in Scottish club rugby history. Two years after arriving in Glasgow to little fanfare, Smith stood at the summit of the URC’s Everest, breathing in the rarified air of Loftus with the league trophy in his arms and champagne foam sloshing all around him. The team – and the coach – who shook up the rugby world.

*** The narrow gate ***

Enter by the narrow gate. For the gate is wide and the way is easy that leads to destruction, and those who enter by it are many. For the gate is narrow and the way is hard that leads to life, and those who find it are few. Matthew 7:13-14.

To understand Smith’s steely assurance and deep emotional complexity, you must go back to a farm in South Africa’s Free State. It was here Smith’s grandparents tended their stock and the boy spent much of his childhood. Sport, the land and a profound Christian faith are strong tenets of a Free State upbringing.

Smith never went to a powerhouse Springbok factory high school. He grew up chasing the green and gold dream, qualified as a geography teacher, and would drive 360km a day between home, work and Griquas training. Even as a young man, his unerring devotion was obvious.

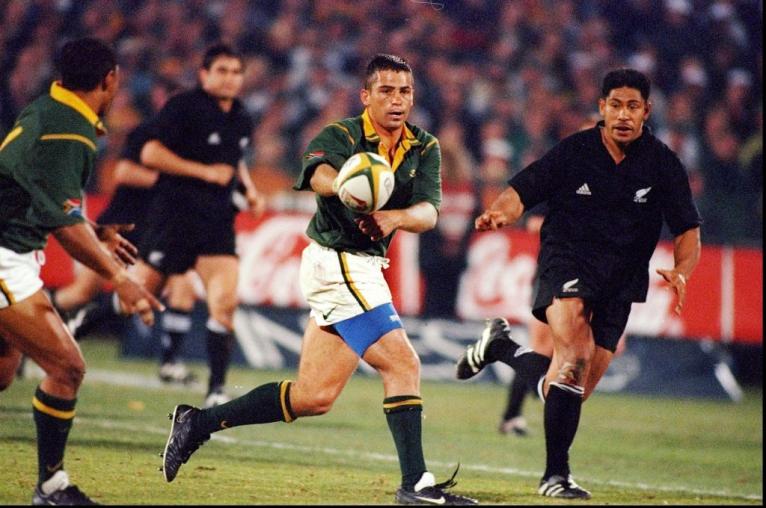

“To come out of a smaller school in South Africa, just to get noticed is tricky,” says Nick Mallett, the iconic Springbok coach who gave Smith all nine of his caps between 1996 and 1999. “It required a lot of determination and that comes through in Franco all the time. He was unbelievably focused.

“He understood playing 10 and 12 really well; the lines of running, playing flat, his passing was beautiful, his grubbers, his kicking – he was immaculate in everything he did. He was the sort of guy, if the Springboks were told they were going to wear Springbok clothes, his shoes would be polished, his suit perfectly pressed, his hair exactly right. He always wanted to give himself the best shot to do the best he could with his talent.

“And he was a serious young guy. Not flippant at all. Not cracking jokes with anyone. He knew how much hard work it took to get to the Springboks. He absolutely relished it and didn’t want to mess it up in any way.

“He would talk rugby all the time. If you saw him at breakfast table he would immediately get into backline moves or defensive strategies or the kicking game. Rather like Rassie Erasmus, two very rugby-driven individuals. Rassie was a bit naughtier and had a bit more fun, he would tease and play tricks on guys. Franco was like the school head boy.”

A rugby team is a kaleidoscope of personalities and backgrounds. Smith was obsessed with the game, but rigidly straight-laced away from it, happy to exist on the social periphery.

“He was never going to be the guy who got pissed, fell around in a bar or sung a song – never,” Mallett stresses. “He was concentrating flat-out to keep his place. There was that vibe maybe he wasn’t a barrel of laughs but as a coaching staff, if Franco was concerned about his role, we’d spend half an hour chatting to him.

“Franco did not have self-doubt but he wanted to make sure there were no areas he wouldn’t thrive in because of a lack of understanding of what we were trying to do. He was never unpopular, unkind or selfish in any way. He was team-driven and wanted to make sure he never let the team down.

“Perhaps, in his mid-20s, you might say this guy takes it so seriously that he’s not much fun. There was never downtime for Franco. Even if he had a beer, it was probably a shandy. I’ve always been very fond of him, really respected him. He was so incredibly proud to represent his country and that shone through in everything he did. I remember him thanking me as though it was something kind that I’d done in selecting him. It wasn’t, he deserved to get there.”

Mallett recalls how Smith took “that whole energy” into his coaching. The desire to wring every last drop out of himself and the lust for challenge. He embraced tough jobs and gritty places. His love of the Free State kept him at the Cheetahs when suitors came knocking. He never applied for a job, never sought the gilded, moneyed heavyweights of the South African scene. He even turned down an approach from Erasmus to return as Springbok assistant, a role he’d held briefly during the disastrous reign of Allister Coetzee. Time and again, the narrow gate was Smith’s route.

“He always had to do it the hard way,” Mallett says. “He was never given the Stormers job or the Bulls job. I think he worked out you needed discipline in a rugby context, the whole squad needed to have standards they had to apply.

“In the Free State, the diet was really important to Franco. If you had a prop who liked a hamburger he was in trouble. Franco said, ‘no, no, no, we have to use every single aspect of our lives to make us better rugby players’. If that was diet, training, sleep, no alcohol, no partying after games, he wanted the team to buy into that.

“If individuals didn’t conform, he didn’t pick them or got rid of them. That whole attitude, he took and got success at the Cheetahs because of it. He could do it there and do it in Treviso – it’s a small family town, guys buy in to that because they hadn’t been particularly successful and he moved them up the table incrementally, consistent with what he did.”

*** Tiramisu and Tricolores ***

Chi se move mangia e chi sta fermo secca – He who moves eats, he who stands still, dries up: Italian saying.

Sebastian Negri remembers the shock of his first few sessions with Smith, as though someone had woken him up with a set of defibrillators and a cattle prod. A huge turnover in personnel was not unexpected after Rugby World Cup 2019, but the physical load Smith placed on his young group was, for many, completely unheard of. They ran and ran and then ran some more. Puddings? No chance. Pastries? Forget about it. On the day Smith’s switch from head coach to national director of rugby was announced, some players posted pictures of tiramisu on their social media to celebrate.

“I’d be lying if I said he wasn’t demanding,” Negri begins. “He worked us harder than any coach I’d had. He demanded we hit metres, hit the right running and collision stats.

“He was very strict on our conditioning, our repeated efforts, that it is an international environment and those are the standards you have got to have. He would just tell the nutritionist, no desserts, no cakes, no sweets. That was his clear message – and he was very, very clear.

“A few players didn’t understand and found it really difficult to adjust. You buy in to that or you don’t and because we were such a young group, we probably didn’t buy in as well as we should have.”

Interestingly, none of Smith’s culinary doctrine featured at Scotstoun.

“Not once did Franco mention the detail around what you and can’t eat,” Berghan says. “Other coaches go around at mealtimes and call guys out. That’s a joke. I suspect that was a massive learning from his time with Italy. He’s been able to show the self-awareness to reflect on it.”

Mallett coached Italy a decade earlier, just as Smith retired from playing in Treviso and began coaching at what became the country’s premier rugby club. He believes Smith placed too many constraints upon players who simply weren’t used to being managed in this way.

“When Franco took the national side, he got players from big French clubs and overseas and they said ‘what’s going on here? This guy is telling us what we have to eat, what we can and can’t do.’ That was very difficult for him. He didn’t have the same control over that side as he did in Treviso. What was disappointing was he’d moved completely down the line of what this present Italian team is doing, he was pushing very early on and the team was quite young, so he was picking the right players but they didn’t have any experience.”

Smith took charge of 13 Tests and lost them all. Yet, as Mallett infers, he laid the foundations for the success Italian rugby is at long last beginning to savour. He played an ambitious attacking game and refused to change the blueprint. He saw 2020 as an opportunity to move on from the titans of yore, the Sergio Parisses and Leonardo Ghiraldinis, and sculpt new Italian heroes. He capped 13 players, many of them mainstays of the Azzurri squad four years and two head coaches later. Roaring captain Michele Lamaro was given his debut. Smith backed Paolo Garbisi at fly-half when he’d scarcely played a URC match for Benetton. Monty Ioane, Juan Ignacio Brex, Stephen Varney and Danilo Fischetti all took their first steps on the international stage on the South African’s watch.

“He has definitely had a hand in the results we are having now,” Negri says. “Think about all those young players – look no further than ‘Mitch’ [Lamaro]. It was going to take time and it didn’t work out for him.

“Did the whole team buy in? Probably not. But I respected the fact he didn’t want to change; it was his way. Looking back, we should have adapted better and had more balance to our game. But I appreciated who he was and the values he had. He is a good family man, an honest person, and I like that.”

What Negri also appreciated was Smith’s contagious and compelling emotion. His commitment burned so powerfully that it sometimes spilled right out of him. If you look hard enough online, there are clips of him crying in Afrikaans after leading his beloved Free State to a second Currie Cup title in 2016. In the Italian inner sanctum, after battles raged and were lost, Negri and Smith shared poignant moments.

“He was very open about his emotions and you could see how much he cared about us as individuals and as a team, I got that straight away. I shed tears with him after games when you’d feel you’d given everything, you don’t feel far off but the scoreboard shows everything. You see how disappointed and upset he is for the team. When you see someone so engaged and emotional about something, I bought in to it, because I knew how much he cared and wanted the best for us.

“I respected that. That’s why I really enjoyed playing for him: I knew what type of person he was, and no matter how good a coach you are, you play for the person before the coach.”

Berghan soon came to see this arresting side to Smith. Each week, Glasgow hold what are called ‘about’ meetings, a concept introduced by Gregor Townsend where a player shares his journey with the rest of the group.

“Often it would be quite a vulnerable conversation. That’s a great culture builder. Guys have had some truly traumatic stuff go on. Franco would then go up and end the meeting and sometimes he would be blubbering. ‘Wow, that was so moving, incredible story, that’s strengthening our team’. He is fiercely emotional. He’s witty. He’s intellectual, super intelligent. A lot of intelligent people aren’t big talkers, they do a lot of observing. I loved that because when people like that speak, I want to listen.”

*** Cheese puffs and broncos ***

“Control leads to compliance. Autonomy leads to engagement.” – Daniel H Pink

The public reaction to Smith’s appointment was decidedly tepid. Supporters were not wholly inspired by his resumé. A few weeks after arriving in Glasgow, Smith sat behind his new desk in a crisp white shirt as this was put to him. He looked down, shook his head, and rubbed at the palm of his hand. He spoke quietly, but with utter conviction. “They’ll eat their words – they’re not the first to have had their doubts.”

To write off Smith’s experience back then was to grossly denigrate his achievements. The Currie Cup wins on a shoestring and the constant rebuilding of a Cheetahs squad ravaged by richer foes. The steady construction of a Benetton team ready to become credible in the old Pro12. Those Italian pups blooded in the ruthless environs of the Six Nations, now battle-hardened and lauded as history-making heroes. Nobody doubts his pedigree any longer. But at the time, with Glasgow reeling from the Leinster embarrassment and the dismissal of Wilson, dissenting voices were common.

“Franco came in and kept us all at arm’s length,” Berghan remembers. “He really wanted to observe what was going on within the club, observe players before he spoke to them. I like to have craic with the coaches and often it wouldn’t go down particularly well. He wasn’t much of a banter king. But after he got a feel for us, and we got a feel for him, he became a lot more personable.”

There were parts of Smith’s previous self which remained, if not quite as starkly. Every professional team has a ‘fat club’, and Warriors carrying extra poundage were placed in what Smith called ‘the cheese puff brigade’ and strapped to Wattbikes. Journalists who repeatedly asked too many questions might be berated for not allowing colleagues their turn to speak. Fairness was at the heart of everything.

Birkenstock shoes weren’t an issue but blasphemy certainly was. When a player knocked the ball on during one of Smith’s first games, a member of the backroom staff cried ‘Jesus Christ!’ in exasperation. He was soon reeling from a smack around the ear. Any further affronts to Smith’s faith might be met with ritual spitting on the floor.

Nor did the new supremo cede absolute control until he really trusted his lieutenants. He’d arrived midway through pre-season, recruited no players and brought no assistant coaches with him. Some senior players recall a stage, during his first campaign, when Smith noticeably empowered Nigel Carolan and Pete Murchie with more responsibility.

“I suspect this was probably an issue in his early coaching career – he did like to have control over what was going on,” Berghan says. “For example, we had Al Dickinson as scrum coach and quite often Franco would take the sessions and coach the scrum. A lot of players at the start were like, ‘why is this guy taking our maul and scrum sessions? It’s brutal. He played stand-off.’

“But that was such an important part of his plan, that first year he was in every single forwards session – coaching, not just watching. He would never do reviews, because he didn’t know, ultimately, why a scrum collapsed, but he wanted to make sure we instilled that steely mindset around those set-pieces. Maybe as an assistant forward coach that would be difficult to manage.”

There was a meticulousness to Smith’s method. The lung-shredding sessions were backed up by sound reason and tempered with more tranquil periods.

“He was really sensible in a coaching sense which I loved,” Berghan continues. “He worked us hard but fairly. There was never any sense of, ‘this is ridiculous’ or ‘this has no value’. We always got a lot of value out of it. Other coaches just flogged the horse because they could. With Franco, if you asked him why we were doing something, he would explain it to you and you couldn’t argue with it.

“We did a lot of running, sometimes 15km the week of a game. Some weeks you’d reflect on that and wonder if you’d done too much, but the following week they would adjust and taper off. The strength and conditioning guys had high expectations but offered a lot of autonomy to the players. They trusted you. There was none of that in previous environments I’d been in, where you’d get punished in some form. There was a real sense of ownership. If you couldn’t be trusted or didn’t meet those standards you’d quickly be found out or lifted up by the guys around you.

“Controversially, but super-sensibly, he gave the guys three months off the following season. Everyone went, ‘wow, that’s crazy, no coach ever does that’. If you have guys with high standards, high autonomy and high levels of trust, they’re not going to let anyone down. What happens? They come in, smash their broncos, and win the league.”

The upshot was a team who could prevail in any number of ways. They could steamroll you with their pack just as easily as shred you with their rapiers. They racked up an absurd volume of maul tries and even more long-range belters. Their set-piece functioned beautifully and their attack was the talk of the URC. Smith wanted tempo and panache.

“Everything had purpose and direction,” Berghan says. “He never swayed from his direction. Getting off the ground, playing a fast brand of rugby – never once did he deviate. Never once did he say, ‘we didn’t do well in that game, let’s go back to eight-man rugby’. Never once. It was hard not to get on board with that sense of purpose.”

For all his resolve and all his demands, Smith has never been a tub-thumping drill sergeant. His oratory is concise but not bombastic. His messaging clear but not aggressive. Yet the Springbok in him never truly faded.

“He wouldn’t speak a huge amount. He wasn’t a bang-your-head-off-the-wall coach but when he spoke, you listened. I liked having craic with coaches and sometimes it hit, sometimes it didn’t. Whenever it did, he would have a wee smile.

“He was fiercely competitive – I’m talking, fiercely competitive. You’d go out and kick a ball around before training and I used to go out and challenge him, tell him ‘I’ll beat you in a drop-goal competition’. He’d just switch. It was almost like his weak spot. We were doing a kick-off practice where you’d lift the locks and he wouldn’t let the kickers do it, he wanted to do it. Duncan Weir is standing there and Franco is practising his drop-kicks – no matter how his kicks went, he was kicking these restarts. We thought that was hilarious because he was so proud and so competitive. It showed he cared. He cared so genuinely about the game and you could never take that away from him.”

*** The heroes of Loftus ***

“Altitude. 1350m. It matters.” – The sign nailed above the tunnel mouth at Loftus Versfeld, the last thing players see before taking the field.

Mallett’s jaw practically hit the floor on that famous night at Loftus. Here were Scots roughhousing the Bulls high in their storied fortress. Nobody fetches up in Pretoria and backs their fitness to see them home. Not here. Not in the asphyxiating altitude. Not against the monsters of the Highveld. Mallett marvelled at muscular fly-half Tom Jordan whacking forwards and jackaling for possession, the cohesion and dynamism of Glasgow’s athletic backline, and the way Smith had tailored his swashbuckling style when the play-offs demanded a pragmatic slant.

“They physically outplayed the Bulls. You would never have said that about a Scottish team. There was no south African front-foot ball and no easy maul tries. Glasgow didn’t concede a maul try, the most incredible statistic, and they’ve scored more maul tries than any other team in the URC.

“The pack, that was the key. You are not going to beat Munster in Limerick or the Bulls in Pretoria without a very hard edge. The backline is very physical as well. It really struck a chord with me to find a 10 who, no-one went through his channel, he was very, very committed. Everyone was a hero in that final.

“The balance in the team was excellent and Franco, to get those experienced players to believe in the way he wanted them to behave during the season, and his approach to the altitude problem, he is a no-stone-left-unturned guy. That was marvellous.”

Negri resisted elements of Smith’s plan at first. He wanted to be charging up the guts, cracking ribs in the middle of the pitch, not galloping up and down the tramlines out wide where Smith felt his bulk was best used. Gradually, he saw things the coach’s way. Smith changed how he thought about rugby and thought about life.

“I really believe Franco made me a better rugby player and a better person, and there is no bigger compliment I can give someone. And he’s done a lot for Italian rugby. As much as it didn’t work out for Franco, he can look back with a lot of pride.

“Every time I see him, I congratulate him. I’m proud of Franco, and proud of what he’s done.”

Berghan retired last summer and took up a job with investment behemoth BlackRock. Smith’s first year at Scotstoun gave him a fulfilling swansong, even if it ended in a gut-wrenching quarter-final loss to Munster then a far more dispiriting defeat by Toulon in the Challenge Cup showpiece. To Berghan, Smith is the epitome of the modern coach. The nimble mind, emotional intelligence and complete belief in his process.

“Franco has learned over his years of coaching what works and what doesn’t and grown and evolved as a coach. A lot of older coaches were ex-players from a previous era who used to just bang their pan in because that was the done thing. That is changing now. Franco was prepared to evolve, learn, stay current and trust his players and the science coming into rugby.

“He is not a liar or a bulls***ter. His values and character are his strength. Was he the most personable guy? Probably not. But he fiercely cared about the person, the team, the player. Would you have him at a stag do for craic? No. But would you have him as your head coach? Absolutely. He was exactly what we needed. That’s how I’d describe him.”

From the arid Free State, through the narrow gate to Treviso’s canals and Rome’s history and onwards, then, to Glasgow. From relative rugby poverty to one of the game’s ultimate accolades. The stoicism and the warmth; the competitiveness and the cunning. In a recent BBC Scotland podcast, Smith described himself as a “dream-giver”. How he has driven these men to seize their ambitions and realise the glory which hung tantalisingly out of reach.

Glasgow know they will be a hunted side this season. Their coach, of course, will have a plan for that.

Franco Smith is a South African through and through and he will be the next Springbok coach after Rassie. Rassie is also a fellow Free Stater and knows Franco well. To be the Springbok coach will be reward for his coaching efforts.

Hopefully not. I’m with Naas Botha on this one. Rassie should coach the boks for the next 20 years.

But if Franco is willing to come in and work with Rassie - I’m all in!!

I think Franco Smith will be the next England rugby coach. Maybe sooner than expected

he won't be.

if borthwick left, Dowson and Vesty would be the frontrunners

That makes more sense than him being the next coach of SA.

However, it would be quite the coup. An Afrikaaner coaching the English team.

Excellent article. I had the pleasure of meeting Franco on Byres Road Glasgow. I congratulated him on his leadership and team achievement and how he has instilled a winning mentality in the team and how much it meant to long time Warriors Season Ticket holders like me. He was welcomig and authentic and his decency and humility were there to see. We truly are in good hands.

Next Springbok coach material

I hope not. Rassie should coach for the next 29 years. Like that Dallas cowboys dude.

Like Naas Botha says - why not?

No way were going to keep him for Scotland 😀

Places don’t come much tougher or grittier than Glasgow. Franco Smith inherited a club that had come badly unstuck and just been ground in the dirt by Leinster to show where they were at. Yet he has turned them around and produced a team that are delivering in a spectacular way in unbelievably short order. Nothing less than miraculous.

Repeating the URC win will be incredibly tough but they will be thereabouts in the knock outs. I have a suspicion though, that he will have a particularly close eye on making an impact in the champions cup this year. Now that would be an entirely different class of miracle…!

Super article. He's worked wonders with Glasgow.

Excellent and insightful article.