We live in an era when the similarities between two of the biggest contact sports in the world, American football and rugby, are too obvious to ignore. Yards-after-contact, screen blocking, chop tackling, the three-point stance and even ‘stickum’ [glue on the hands to help catch the ball] are all concepts rugby has borrowed from the NFL.

Ideas flit freely between the two games, and they fly in both directions. So do the problems. Eight years ago, current Racing 92 head coach Stuart Lancaster was one half of a transatlantic conversation with the Superbowl-winning coach of the Seattle Seahawks, Pete Carroll. The NFL was looking to teach rugby tackle techniques, lowering body height to avoid the post-traumatic effects of helmet-boosted head-to-head contact. In both sports, there has been a very public drive to make the game safer for the players who participate in it.

One of the newer ‘deals’ going the other way is the refinement of blitz defence in rugby, based on the same theory in American football. Full-on blitz is still a surprisingly rare bird in union, despite South Africa’s high-profile success with it at the last two World Cups.

A main plank of that theory is the idea of the ‘front seven’ [defensive linemen and linebackers] looking to shoot gaps in the offence, rather than take on the men directly opposite them and read play off their actions and movements. It is also the Jacques Nienaber way, and the foundation of the system he is now embedding with Leinster.

The crucial battleground in Saturday’s semi-final at Croke Park was always going to be the contest between Northampton’s class-leading attack and Leinster’s rabid, South African style defence. The top two attacking teams in the English Premiership – Saints and Harlequins – were both represented in the semi-finals and led most of the categories which matter [active time-of-possession, number of rucks built, ratio of lightning quick ball] in their league. The Dublin province had only conceded five tries in four EPCR matches at the pool stage, so the scene was set.

As Leinster skipper Caelan Doris commented ruefully after his side’s nail-chewing 20-17 victory:

“We came together and acknowledged there was a bit of a lull, they were going through a bit of a purple patch [in the last quarter].

“Some of that was through our discipline, giving away back-to-back penalties which gave them entry into our half, but I think it is credit to them as well. They are top of the Premiership for a reason.

“When we were scouting them, we saw their attack as one of the best we are going to face this season, and you saw some of that in the second half as well. As much as we back our D, their attack probably got on top of us at times there.”

From another perspective it was also ‘England versus Ireland part two’, with 15 of the Leinster players who had represented Ireland in the 23-22 loss at Twickenham in March now wearing the blue of their province, and two key outside backs who started for England [Tommy Freeman and George Furbank] in Northampton colours.

One of the major platforms for England’s win was the effectiveness of their kick returns, with Furbank the main instigator from the back. Only five of England’s 16 attacking possessions that day ran for more than four phases, and the men in white made hay from six kick return ‘set pieces’ instead.

The first example occurred in only the fourth minute.

Furbank sets off on a long cross-field run from inside his own half, and the Irish defence waits for the four defenders on the far side of the field to connect before attempting a stop on Tommy Freeman on their own 40m line. That means all the attackers beyond the big Saint are already in play if England can move the ball away from the point of contact quickly. Furbank recycles himself into the next play off quick ruck ball and the men in white have the numbers for Lawrence to convert in the left corner.

Leinster under Nienaber take a very different stance in defence.

The return starts from roughly the same spot but the outside man in defence [number 12 Jamie Osborne] makes a stand much further upfield than Calvin Nash did at Twickenham. The tackle line is higher and Northampton wing James Ramm is still trying to realign on attack as Furbank makes his pass to Freeman. More pressure, and less time and space means more mistakes.

Later in the half, a booming exit off the boot of James Lowe was covered in much the same way by the Leinster chase.

The chase line is that much higher and forces Furbank to pass the ball forward to Freeman on the left edge. It was another win for Nienaber and indirectly, another tactical lesson learned from the England-Ireland encounter.

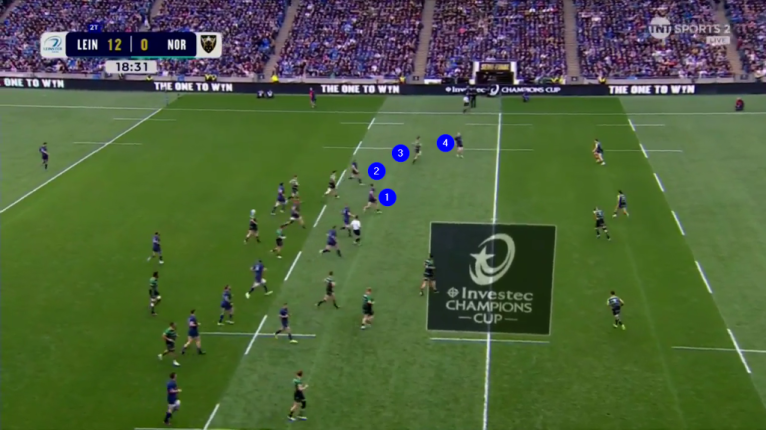

The first seven Northampton attacking platforms in the first period all ended in turnover, and it was no better from set-piece than it was from kick return. Under the auspices of inventive attack coach Sam Vesty, Saints love to probe both edges of the lineout defence. With their throw under constant pressure [nine of 13 feeds went to Courtney Lawes at the front], Nienaber was free to unleash an NFL-style gap-blitz to stymie any forward progress.

The Leinster forwards are not concerned with marking men and reading off their actions, they are rushing gaps and looking for turnovers, with hooker Dan Sheehan inches away from intercepting the pass from Alex Mitchell in the second clip.

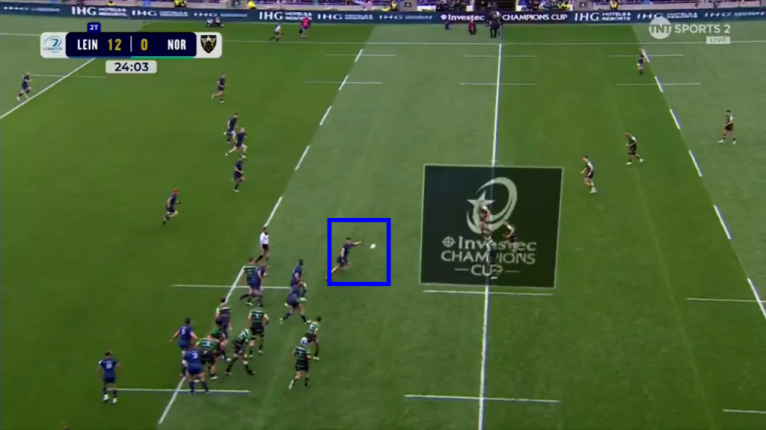

Possibility became reality in the 14th minute, with Ross Byrne’s breakaway interception of a telegraphed Fin Smith delivery off the left hand.

Once again, there is absolutely no intent to mark the man or keep the play in front of the defence. The Nienaber philosophy is all about shooting gaps, attacking the space in between runners and passers, and creating turnovers off the mayhem that ensues.

Leinster controlled the game with an iron defensive fist for the first hour of the game, moving smoothly into a commanding 20-3 lead and only allowing the Saints one line-break just before half-time.

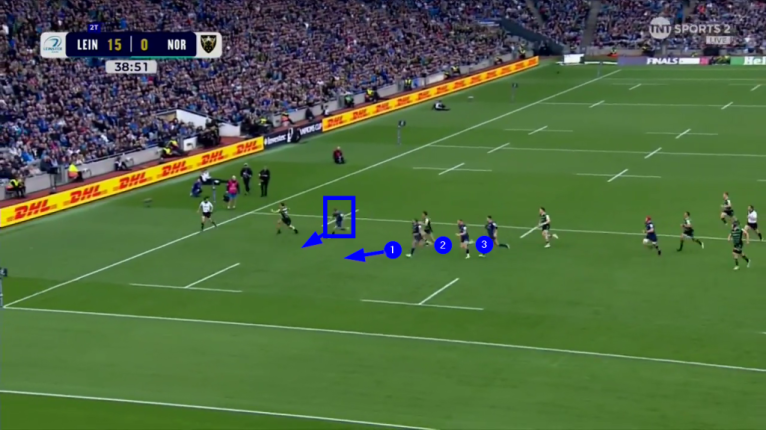

A defence which plays the gaps so religiously will always give up the occasional big play, and this time Smith gets the ball away a split-second before the defenders can reach the passing channel outside him. That is where Nienaber plays his second trump card. After the break has been made, the high line of D still leaves space for no less than three Leinster defenders to hare for the corner flag in cover, not least loose-head prop Andrew Porter. Everyone fights, or runs, and absolutely nobody quits.

Teams in the Premiership, and for that matter the Top 14, do not have much as experience of top-shelf blitz defences as their counterparts in the URC, who will encounter the likes of the Sharks, the Stormers and now Nienaber’s Leinster as part of their regular routine.

The shock of the new was etched on Northampton faces for the first hour of the semi-final, and the lead Leinster established in that period proved too much of a head-start for the Midlanders to claw back.

Will Toulouse be better equipped than Saints to handle Nienaber’s concept of ‘offensive defence’? Maybe not. Just one more five-star performance without the ball could embroider that longed-for fifth star on the jersey for the men in blue: a champions corona, a halo above the harp.

Does a blitz defence not have a weekness against a well-placed grubber kick, perhaps angled cleverly. All the defence is up and the full-back can only cover so much ground. Thoughts?

It’s an ongoing dialogue Rory! Attacks often drop in a short kick behind the line to get at least one of the outside D’s turning back in, or delaying the rush - though ultimately it is also true that the D’s aim is to force a kick by the A, with a chance for them to collect possession.

Whats interesting now is the evolution of rugby. More and more the laws are favouring the team in possession and the ball carrier. Teams can keep the ball for longer periods more than ever before with little risk and wear down defences as long as they don’t knock it on. Set pieces are seen as hindrances and as time wasting annoyances by law makers and they are being depowered as lawmakers strive for higher ball in play time. Perhaps its only natural then that teams will take a more assertive and aggressive approach in defence. An offensive defence as you said Nick. This may force errors and turnovers and help teams to break up attacking plays while providing counterattacking prospects. Perhaps we will see more and more teams adopt the blitz in the next 4 year cycle and beyond much like Gegenpress has met Tiki Taka in football. Instead of Pep and Klopp we will have Farrell and Nienaber.

Gegenpress and Tiki Taka - very nice Shay😁

Yes it does have sound logic - you press to get the ball back as soon as you’ve lost it!

Thanks for the article, Nick. The Nienaber blitz D does ask a lot of its scrumhalf. I have been watching JGP on D and he often looks like he has mastered what Nienaber asks for better than Faf de Klerk and Cobus Reinach! 🤣 Impressive season by JGP if I must make an understatement.

JGP used to playing the backfield with previous Leinster!

Thanks for the lesson Nick! I presume that targeting gaps is situational because if a ball carrier straightens the line they can't be allowed a gap to run into?

It feels like you need depth if you're going to pass it wide and plenty of variety - straight running, kicks just in behind, cross kicks etc.

BTW what an incredible bench Toulouse had this week. People complain about Leinster being stacked but they need to be at the very highest level.

It’s surprsing how SA have found ways to blitz hard off th line even in unpromising circumstances JD - like when they were broken on the previous play…

Coming from the outside in on the tackle means the gap is pretty thin and not easy for the B/C to penetrate at all. More depth on attack means more time for that cover in the second line to plug any leaks!

Yes it’s become a bit of a monopoly and I’m working on a piece about it. The top two hookers in France both at the same club?? Nepo cannot even get in the matchday 23??

I wasn’t aware that the blitz targeted space so, as usual, something learned from reading one of your articles, Nick.

Watching the game live I attributed the Saints’ inaccuracy to their own mistakes and nerves. Perhaps some credit to the Leinster D.

It’s not easy for passers and runners to stay connected when there is so much ‘flak’ coming their way DM, and Saints would not have faced this kind of D in the Prem, they took an hour to even start working it out.

great article! I wonder whether we will we see Ireland adopt the Nienaber blitz? All the teams who have tried it so far (SA included) have gone through significant teething problems in the first season; Ireland could possibly be in the unique position of being able to switch to a hard blitz in season 2 of a world cup cycle and already have so many players used to the system that it can be implemented seamlessly.

I don’t see it happening at national level Finn. From what I know, I doubt either Faz or Simon Easterby would adopt it, even with such a high prooprtion of Leinster players in the same team….

If they were to it'll be in 2026. Farrell's away with the Lions for 2025

A potential 5th star for Leinster and redemption adter losing 2 tight finals against La Rochelle against Toulouse and the chance for Jacques Nienaber to have some success without Rassie Erasmus running the show.

I feel Leinster will be more comfortable playing Toulouse than they were LAR. Toulouse not so good at squeezing the game and denying the opponents opportunities, but Leinster can apply a lot of pressure on Dupont et al. with that D!

Excellent analysis Nick as we have come to expect. I was not really aware that NFL strategies have been adopted by rugby teams, especially in defence. One point I would make is that the Northhampton attacking player on the end of the chain in the video examples has not maintained the correct depth to be effective. In the footage shown the outside player is too flat to make the best of the opportunity his inside players have provided. In each case they have to reduce speed and turn their body backwards to secure the ball, losing all momentum and giving the impressive scrambling defence the chance to shut down the threat.

“One point I would make is that the Northhampton attacking player on the end of the chain in the video examples has not maintained the correct depth to be effective.” Great point, W. And one does see this so often at all levels. The passer often has little option but to pass far too flat, or to avod the forward pass, put the ball on the hip/behind the outside player and as you point out “they have to reduce speed and turn their body backwards to secure the ball, losing all momentum”

There is always a constant to-and-fro of ideas W. Even Jack Gibson the great League coach developed his philosophy by constant contact with the San Francisco 49ers back in the 70s and 80s.

I think the problem with a Nienaber type rush is that it compresses the space for the attack so quickly and forces decisions to be earlier than they would be otherwise, under ‘normal’ conditions. Hence the forward passes and errors in realignment.