Before the All Blacks’ end of year tour set off for Europe, Scott Robertson was asked a leading question by the local media about the repeat selection of senior internationals TJ Perenara and Sam Cane. He laughed it off: “You’re framing me nicely there, mate.”

The real question is whether Razor has been setting himself up for a fall by holding on to known quantities for too long for the good of his team, and that is no laughing matter for New Zealand rugby supporters. Historically, New Zealand has been the most audacious rugby nation on the planet when it comes to whipping new talent boldly off the provincial conveyor belt and into the front line.

The Kiwi supremo went on to justify his preference for experience over new blood as follows:

“It’s always a balance between having experience, guys who are Test-fit, [the] balance of leadership and what it takes to win up north.

“They have got a lot of those qualities. They are in a Test team playing good footy still. That was part of it.

“They can build, they can be a big part of helping the next [generation of] players come through, and building for the future. [Not only] how do we get the best out of them, but how do they get the best out of the next young All Blacks so they can see them come through?

“Spend a bit of time with them, and show them what Test football and touring is all about. Sam [Cane] has got a couple of roles on the field, [as well as] being a good mentor off it.

“Cohesion is really important as we go north. All those combinations and relationships count. We’ve kept a tried [and trusted] combination.”

Cohesion. Leadership. Mentoring. Test-worthiness. Those are the key words that always crop up when Robertson talks about his aims in selection. Flip the coin over, and the reverse is rigidity and stagnation; hanging on to experience for the sake of it, long after its true value has passed.

The essence of the conundrum can be best illustrated by a comparison with the selection process implemented by the current world champions South Africa in 2024. Robertson has gone on record with his admiration of Rassie Erasmus’ ability to integrate veteran overseas players within his depth chart, but the underlying reality is Rassie is a bolder selector than Razor, and far more likely to embrace risk under pressure than his counterpart from New Zealand.

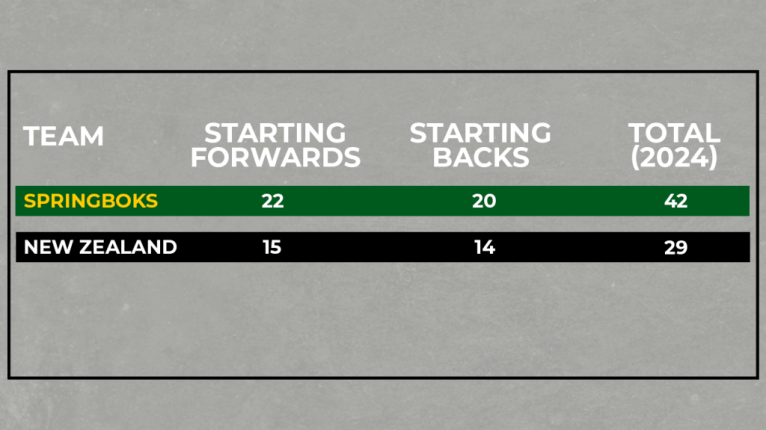

The following table outlines the number of different starting players utilised by both coaches against opponents from either the Rugby Championship or the Six Nations in the course of the season. Both teams played 12 games against their antagonists from those two competitions, with the All Blacks winning eight and the Springboks 10.

There was only position [scrum-half] where Razor tried three other players before settling on Cam Roigard, who returned from injury to start the final two matches of the season. By way of contrast, Rassie selected four different options at five separate spots: tight-head prop, lineout skipper [number five], number eight, scrum-half and fly-half, while exposing 13 additional players to the rigours of international rugby.

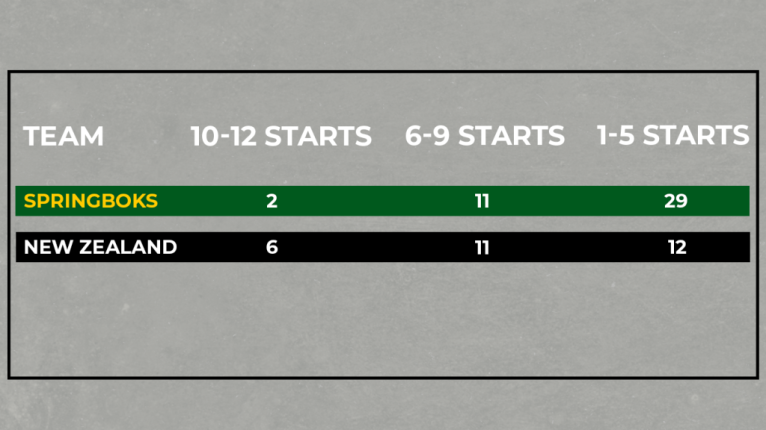

A second set of numbers illustrates the narrow, ‘vertical’ axis of All Blacks selection compared to the Springboks’ wider ‘horizontal’ spread very well.

Where Robertson depended heavily on Tyrel Lomax, Codie Taylor and Ardie Savea up front; and Jordie Barrett, Rieko Ioane and Will Jordan behind, only loosehead Ox Nche and centre Jesse Kriel fell into the same ‘indispensable’ 10-12 game category for Erasmus. Neither world player of the year Pieter-Steph du Toit nor all-world second row Eben Etzebeth were automatic selections despite the undue influence they exert on games in which they play.

The spread at the bottom end is nothing short of spectacular. Seventeen more South Africans than New Zealanders started between one and five games in 2024. The South African selection base is very wide and stable, for New Zealand it is tall but narrow at the base. It is an ironic reversal of history when you recall the accusations levelled at Sir Graham Henry’s rotation policy ahead of the 2007 World Cup.

The All Blacks may have been unexpectedly upset in that tournament but the exposure of so many good, young players set the stage for a decade of untrammelled success to follow. The selection formula is built to survive the high winds of long-term injury and overseas departures far more robustly.

One of the players who has left New Zealand is Jordie Barrett, who started 10 games for his country against top-tier opponents in 2024. He has only moved to Leinster for a six-month sabbatical, but it does raise the question of the depth chart behind him. Yes, there is Anton Lienert-Brown, but he does not have the same skillset or even the same physical profile as the man he replaces. Beyond that there is an echo-chamber of selectorial silence.

The early signs are Barrett will be good for Dublin, and Dublin will be great for the youngest of the rugby-playing siblings. After an outstanding 40-minute debut for the east coast province against the Bristol Bears in the Champions Cup, Barrett commented on Premier Sports:

“I’ve only been here for 10 days but I had a great week [of preparation]. [Ireland centres] Robbie Henshaw and Gary Ringrose have been awesome this week and [they] made my job a lot easier. I am loving my time in Dublin.

“My body was in good condition when I left Italy a few weeks ago, I was chomping at the bit to get an opportunity with Leinster. I know it’s been in the making for six months but I couldn’t wait to get to Dublin, get around some great coaches, some great players. The city of Dublin [itself], and even people all across the other provinces in Ireland have been outstanding.”

“I wanted to come up here and test myself in these big European rugby games. Tonight was a great test and Bristol were outstanding for the most part. I love the way they play, it’s so refreshing to see a team with no fear and they’ve been going well under Pat Lam, so it was great.”

When he returns, Barrett will bring back gifts to New Zealand on both sides of the ball. The Jacques Nienaber-masterminded defence has Jordie attacking man and ball or the gaps between attackers, rather than standing off and reading the play as he does for the All Blacks.

Number 23 is on point for three important turnovers in the second period as Leinster restricted the free-scoring Bears to two tries in the game, down from their 5.1 average in the Gallagher Premiership. Nienaber will plan many more blitzes, rushes and stunts than Barrett is used to back home, and it will help showcase his physical impact on defence.

On attack, Leinster immediately recognised the potential for Barrett’s use at first receiver the All Blacks too often neglected. He enjoyed five touches at first receiver in just half a match, only two fewer than he had in the tour game against England where despite having the best run/pass/kick balance of the three potential playmakers, Jordie was handed the controls all too rarely.

Not so at Ashton Gate, where Barrett shared the playmaking duties with young home-grown sensation Sam Prendergast.

When Jordie’s physical threat at the line forces the defence to sit down and take root, he has the touch on the pass to release the true 10 behind him. It is the sort of natural adjustment for a player with ‘triple threat’ potential any attack coach worth his salt would make. Now imagine Damian McKenzie, Beauden Barrett or Richie Mo’unga in behind the 12 on the end of that second pass.

The youngest Barrett went on star twice at first receiver in Leinster’s third try.

Once again, Barrett is standing right in the teeth of the defence when he drops off the inside pass on first phase, and it has the bonus of adding his considerable physical bulk to both the first two cleanouts. When the time comes for the kill, Barrett is back where he belongs, cutting back against the grain against a Bears’ defence over-reading the pass to score on the run. It is the kind of decisive play from first receiver the All Blacks have sorely missed.

There is a streak of conservatism in current All Blacks selection which is in danger of halting forward progress. Holding on to experience until it becomes merely ‘old’ is highly untypical of New Zealand, and it has given Rassie’s Springboks a head start in the race to the 2027 World Cup.

Where the Kiwi selection tree grows tall and narrow, South Africa’s oak spreads strong and very, very wide at its root. It allows for more absorption of nutrients from the soil and moisture from above, and it is more resistant to natural disasters. Right now, Rassie’s world is growing more leaves and blooms than Razor’s.

Why can’t this be fixed?

Too many long threads with junk comment clogs the system up.