Every day, Glasgow’s pre-season training began at 9am sharp. And every day, Sione Vailanu arrived at Scotstoun for 7am, heaved his mighty Tongan frame astride a Wattbike, and went to work. The Warriors gym, nestled beneath the main stand, became his second home. Extras on top of extras. Lungs and legs screaming. Sweat sloshing across the running track before most of his new team-mates had clambered out of their cars.

Vailanu fetched up from Worcester via a long, indulgent and carb-heavy summer. His weight had ballooned to 143kg. Enormous, even in a game which has become the domain of titans. Unheard of for a 6ft 1ins back-row. Glasgow list their hulking Lions prop Zander Fagerson as 17kg lighter.

“I went on holiday after the season ended, switched off from rugby and did whatever to make me happy,” Vailanu tells RugbyPass+. “I realised I had one more week before the start of pre-season and it was too late to do something.

“I was out of shape and lazy, lazy… The first day of training, I felt old. I saw from the start it was going to be tough. The way they were training was all about intensity. I had to sacrifice a lot.”

In what every Glasgow man attests was a heinously tough pre-season, Vailanu torched 15kg of excess beef. He has become not just the wrecking ball the club craved, but a player capable of big moments deep into matches, a huge part of their unbeaten home season, their rise to the URC play-offs, a giddying Glasgow showdown with Munster, and first, the intoxicating prospect of a first Challenge Cup semi-final at Scarlets on Saturday.

“Even now, the strength and conditioning coaches are like, ‘wow, how have you done that?’. I’m so grateful to the staff who helped me get back on track.

“I’ve been at champion clubs but I’m always thinking, how can I get better, and how can I achieve something. I willed myself to fight. I came in early in pre-season to try and be ahead of the boys. We had our programme but I was always trying to sneak in and do something extra. I’d go to the pool, manage my food, do whatever I could.

“I knew being overweight, I was not going to be playing well, a new coach was coming in, I wanted to make sure I was really fit otherwise it was going to be a tough season.”

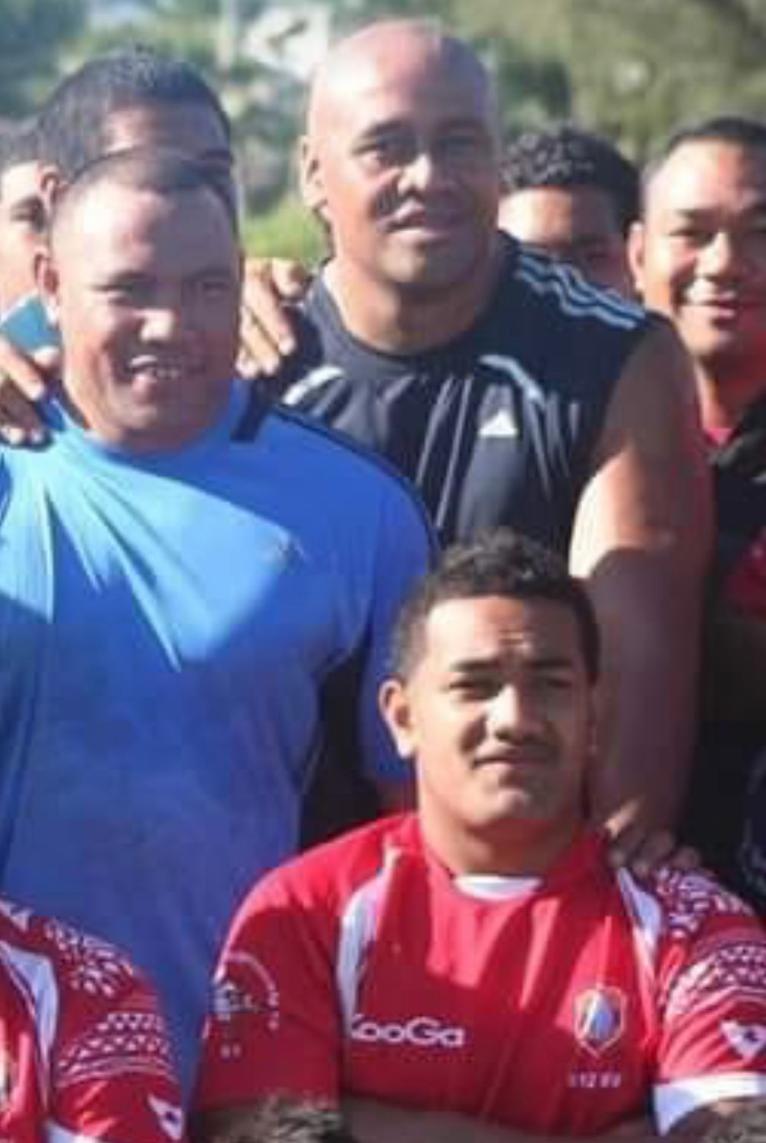

Vailanu knows all about toughness, in a way most British players will never truly understand. He grew up in the tiny, and beautiful, village of Hihifo, set on an island some 300 miles north of the main Tongan atoll. His clan made up a sizeable chunk of the 300 or so village inhabitants – by numbers and body mass – what with his six brothers and one sister. Mahe, the baby of the brood, is now a hooker with the Waratahs. Twenty-eight-year-old Vailanu was the second-youngest and right from the start, infatuated by rugby.

My uncle told me often, ‘you might make a difference, you might change our family’, so I pushed myself.

He feasted on the sporting exploits of the community elders. As he grew older and his ability became obvious, he played for all the national age-grade sides from Under-16s to Under-20s. The great Jonah Lomu, whose parents were Tongan, would fly back to see them and pay the young tyros a visit. For Vailanu, it was like hearing a rugby sermon from the almighty himself.

“He encouraged us, he used to come all the way back to give us some advice and help with our rugby. He always talked about physicality – being Tongan, you let the opposition know it’s going to be physical. We were happy. We knew he was Tongan. We were so proud of what he had done for the All Blacks and for rugby.”

Yet Lomu was not Vailanu’s ultimate idol. He places his uncle, Ha’unga Fonou, on a supreme pedestal. Fonou was part of the first Tongan side to tame a Tier One nation, beating the Wallabies in 1973, one of seven full caps the scrum-half claimed. He lives happily in the United States these days but for his nephew, the influence burns on.

“My uncle is my hero. He played rugby with me after every training session. He told me often, ‘you might make a difference, you might change our family’, so I pushed myself.”

One January morning last year, Vailanu’s people were riven by horror. Vailanu awoke in Worcester to a startling array of news stories and local footage. An underwater volcano near his island had erupted, triggering a tsunami that ripped across the Tongan archipelago. Hihifo was devastated. For several fraught, traumatic days, he had no means to contact his parents.

“It happened at 02:00 here. I woke up, didn’t know what happened, and just saw the news from Australia and New Zealand, and a few videos from Tonga. Where we live is low and flat. I was trying hard to connect with my family but after the tsunami, everything was cut off – internet, cell phone coverage.

“I asked Worcester for a day off, phoned the head coach and told him my head is not rugby-focused, I could not think about anything except my family. I just wanted to know, are they safe? Are they well?

“What could I do? I sat there thinking about my family and what they were going through. Luckily I found out they were able to get away early, knowing the eruption was coming, to the other side of Tonga where it is higher. If my family hadn’t prepared well, it would have been a different story.”

I always challenged myself. if I go back to Tonga, what should I do? So many people really, really want my opportunity.

Even now, 13 months on, the painstaking restorations are not complete. Vailanu and his Tongan pal, Malakai Fekitoa, launched a fundraiser which received over £70,000 in donations. Charles Piutau and Hosea Saumaki set up similar initiatives.

“The village next to ours is completely out,” Vailanu goes on. “The King of Tonga has changed the laws, no-one is allowed to stay in that village any more, they moved them to the other side of the island. My village is quite damaged but they are slowly rebuilding. We are so grateful, a load of fundraising has been done in Japan, Australia, New Zealand.”

It has been a decade since Vailanu lived in Hihifo when, as an 18-year-old, his school team competed at the prestigious Sanix World Rugby Invitational Tournament in Japan. He had never left the islands before, but impressed sufficiently to be offered a scholarship, by Asahi University. The Nagoya metropolis of over two million people was wildly different to the beaches of home. Vailanu spoke no English and no Japanese but took intensive classes until he became fluent in both.

“Sometimes home feels far away, you miss your family. But I always challenged myself, if I go back to Tonga, what should I do? So many people really, really want my opportunity, especially in Tonga, where there are so many good players who are not able to get out.

“After two years in Japan, another Tongan guy came. He went back to Tonga after a week. I always told myself to attempt what the Japanese do, learn their culture, learn their language to adapt yourself otherwise you’re going to end up going back to Tonga.”

In 2019, Don Barrell, the former Saracens academy director, came across this ball-carrying behemoth at a tens tournament. Vailanu leapt at the chance to join the English heavyweights on trial.

“I didn’t even know there was rugby in Europe – I was fresh from Tonga in Japan. I was selected to play for Samurai Tens and Don was the forwards coach. I was really, really happy to go to Saracens.

“I was quite lucky because Billy and Mako Vunipola were there. I came to a country where you had to speak proper English to be understood. I stayed with Billy and he helped me with the language and the rugby.”

Vailanu did a year at Saracens, two at Wasps and another at Worcester, winning Test honours along the way, before Danny Wilson brought him north. He never actually played for Wilson, with the coach sacked at the end of last season, sparking more anxiety about what a new supremo would make of his bulging post-holiday midriff.

When I played in England, I couldn’t play 80 minutes – maximum, 50 or 55. I was surprised here, playing 80 almost every week.

But under Franco Smith, Vailanu is playing the rugby of his life, underpinned by the immense toil of the summer. No longer do we see a massive carry followed by long minutes of inactivity. He is a constant, telling influence, splatting tacklers, burgling breakdowns and using his deft handling skills. He is Glasgow’s most prolific URC carrier, averages seven metres per charge, and has hoovered up more yardage than any other Warriors. He is second for tackle breaks, third for line breaks, and second for breakdown steals.

“When I played in England, I couldn’t play 80 minutes – maximum, 50 or 55. I was surprised here, playing 80 almost every week. When I look back now, the effort I made during pre-season has really helped me. Now I can carry, get up, do it again, tackle, win a turnover, for 80 minutes.

“South African coaches love being physical. Franco fit in so well for me. He said to me, ‘always be yourself, I give you a free licence to express yourself – don’t worry about anything’. That’s made me push myself even harder. Franco encourages me to do what I like and be able to trust me in what I’ve done.”

That trust is being repaid in great Tongan fistfuls, all the way to the Challenge Cup semis and the URC play-offs, fuelled by family pride, a rugby obsession and of course, the dreaded Scotstoun Wattbikes.

Well written piece on a very good player - well done, Jamie