There’s a relatively new concept doing the rounds among observers of nature. It’s known as shifting baseline syndrome.

It centres on the idea each new generation of humanity fails to fully grasp the damage that’s been done to the planet because they don’t know what the planet looked like before they were born.

As a result, further damage is tolerated on the next generation’s watch because, relatively speaking, it doesn’t appear that severe. We only know what we see.

We see vast open fields of wheat and corn and assume they are beautiful, when in fact they are barren deserts once teeming with life.

We assume massive 30 tonne tractors thundering up and down our country lanes have always done so or giant mechanised combine harvesters with unforgiving, threshing rotor-blades have always ripped up fields in August, leaving nothing but dust and scorched earth.

The industrial processing of our land which only began around three centuries ago has, however hideous, become culturally normal. In relative terms our baseline has shifted astonishingly quickly, so on we plough.

Shifting baseline syndrome is far from restricted to our observations of nature. Take the observation of sport for example, and more specifically the observation of professional rugby union.

From 1995, when the sport turned professional, to last year’s Rugby World Cup the average weight of an international player rose from 94.8kg (14st 10lbs) to 105kg (16st 5lbs).

In that period, international schoolboy teams grew comparably and England’s Under 18 team is now routinely man-for-man heavier than Will Carling’s 1991 World Cup heavyweight finalists.

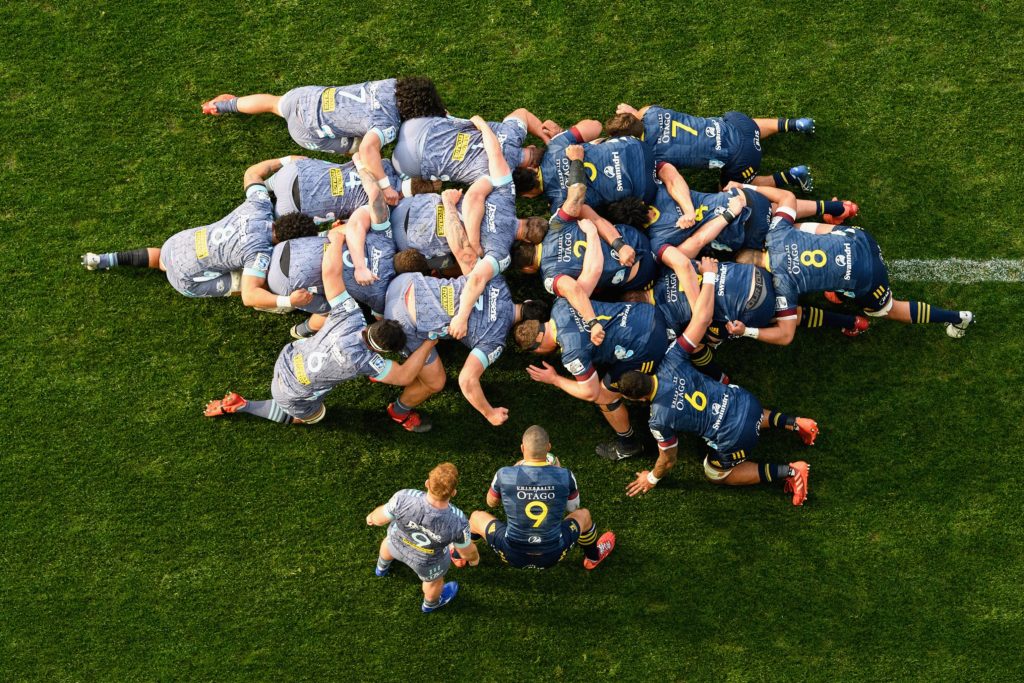

In the same period the tackle has become the hit, contacts have become collisions, extreme injuries have become the norm, size has become king.

England’s Under 18 team is now routinely man-for-man heavier than Will Carling’s 1991 World Cup heavyweight finalists.

Despite the undeniable increase in force (Newton’s second theory of motion tells us Force = Mass x Acceleration), the fixtures come faster than ever. No time for rest. Win at all costs.

As each new generation encounters a sport which once could honestly say was “fit for all shapes and sizes”, shifting baseline syndrome kicks in. The landscape has changed beyond all recognition but the new normal, however grotesque and extreme, is blithely accepted by those who observe and participate.

The Gallagher Premiership returned recently with a cohort of young men who were bigger, faster and stronger than ever before. Bigger certainly than when lockdown began.

One well-placed source at Sale Sharks told me recently: “It looks as if the lads have spent lockdown eating nothing but raw meat”.

Sale weren’t alone. After all, it’s much easier to coach bulking up and aggression than it is to coach spatial awareness and sleight of hand.

“Come back when you’re bigger,” is far more measurable and tangible than “come back when you can thread a 20 yard pass off your wrong hand through the eye of a needle.” Professionalism has robbed rugby of subtlety and nuance. Brute strength and power have won. As a result, rugby’s soul has been lost.

Get big, get rich. All the clubs will have been at it. Within a couple of rounds of fixtures, we’ll hardly even notice. Baseline shifted. Next season, they’ll shift again.

Professionalism has robbed rugby of subtlety and nuance. As a result, rugby’s soul has been lost

The injury rates in professional rugby union have been intolerable for many years now but those of us who cover the sport for a living have also succumbed to shifting baseline syndrome.

We see at first hand the physical toll the professional sport inflicts on it’s players but those who call it out are derided as “troublemakers” or even God forbid “not rugby men” by the dinosaurs and money-men whose territory we threaten.

The Premiership’s relentless fixture schedule, which has surely now crossed the line from reckless to criminally negligent, will do even more damage to brains, bodies, families and, ultimately, the reputations of those who have allowed it to happen. A price will eventually be paid.

“You’re seeing injuries now you’d more normally associate with serious road-traffic accidents,” Wales head coach and former traffic cop, Wayne Pivac told me a couple of years ago.

You’re seeing injuries now you’d more normally associate with serious road-traffic accidents

Wayne Pivac, Wales head coach

“I’m talking about knees which have been obliterated, completely blown out. Hamstrings ripped off the bone. The boys need looking after.”

Two years later, nothing has changed. In fact things have got far worse. The new-look Gallagher Premiership fixture schedule, which sees players forced to back up games four days apart, is nothing short of an abomination. Player welfare has been dumped out of the window. Parents, the gate-keepers to players of the future, will not fail to take note of how callously and cynically those at the top are treated.

People often say it will take a death on the field for anything to change but plenty of rugby players have already died and only a handful involved in the professional sport have seriously attempted to hit reverse, slow things down, de-power the game. Affect change. Save lives.

Last September 25-year-old RAF Airman Scott Stevenson received three blows to the head in one game but carried on playing only to collapse on the field and die in hospital, with his mum and dad by his bedside, three days later.

In a hellish eight-month period between April 2018 and January 2019 four young players died from injuries sustained on the field. The deaths prompted a brief outpouring of dismay and outrage in France.

Strength and conditioning has created a monster

Peter Robinson, whose 14-year-old son, Ben died from repeated head injuries sustained in a school game in 2011

Action was promised by World Rugby. A player welfare symposium in Paris was hastily convened by the powers that be. Lip service was paid. Beer was drunk; lots of it in fact. Laughs were had. A press conference was held. Nothing was done. The storm passed.

But it will return.

“Strength and conditioning has created a monster,” said Peter Robinson, whose 14-year-old son Ben died from repeated head injuries sustained in a school game in 2011.

“The game at the top now is unrecognisable from the game played 20 years ago or the one I played when I was a lad. Can you imagine if Phil Bennett or Jackie Kyle came on the scene now? They wouldn’t get a look in.”

Rugby players are too big, injury rates are too high, matches are too frequent.

Players may be bigger, stronger and faster and the hits may be harder than ever before but at what cost?

The true extent of the damage to players – denied for so long by the authorities and professional rugby’s self-serving money men – has never been clearer. Yet we deny what we see. Shifting baseline syndrome, you see.

For the time being at least, professional rugby union ploughs on. It leaves behind a trail of dust.

If you’ve enjoyed this article, please share it with friends or on social media. We rely solely on new subscribers to fund high-quality journalism and appreciate you sharing this so we can continue to grow, produce more quality content and support our writers.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free