The week before the second test between South Africa and the British and Irish Lions was marked by an unprecedented hour-long video critique of the referee, Australian Nic Berry, by the South Africa Director of Rugby, Rassie Erasmus.

None of Erasmus’ criticisms would have created more than a mild stir if they had been raised through the usual channels – the regular meetings between coaches and the officiating crews which precede every big match. The fact that they were aired through social media was a new and unwelcome departure from the protocol.

World Rugby finally responded to the critique a couple of days after the game had been played, and won by the Springboks:

“South Africa Director of Rugby Rassie Erasmus and SA Rugby will face an independent misconduct hearing for comments regarding match official performance during the test series between South Africa and the British and Irish Lions.

“Match officials are the backbone of the sport, and without them there is no game. World Rugby condemns any public criticism of their selection, performance or integrity which undermines their role, the well-established and trust-based coach-officials feedback process, and more importantly, the values that are at the heart of the sport.

“Having conducted a full review of all the available information, World Rugby is concerned that individuals from both teams have commented on the selection and/or performance of match officials.

“However, the extensive and direct nature of the comments made by Rassie Erasmus within a video address, in particular, meets the threshold to be considered a breach of World Rugby Regulation 18 (Misconduct and Code of Conduct) and will now be considered by an independent disciplinary panel.”

The scope of Erasmus’ criticisms went far beyond the decisions made by an individual referee. Top coaches want the game to evolve in the direction which suits the strengths of their teams the best, and it is this which provides the most interesting context for an understanding of the 62-minute outburst.

The major law tweaks since the 2019 World Cup, and the hiatus in activity enforced by the Covid-19 pandemic have focused attention around two issues: player welfare and the danger of repeated concussions and head traumas; and streamlining the law interpretations at the breakdown. The latter is a perennial bugbear in a law book which contains 11 sections and 25 sub-clauses on the tackle alone.

The idea is to generate quicker turnovers for the defence via an immediate ‘lift’ of the ball, or quicker ball for the attack with defenders releasing and clearing out immediately. That is the way it has worked in other competitions globally, like the English Premiership.

In mid-2020, a very clear and concise summary of the law amendments was made in this video by the NZ Refereeing Director Bryce Lawrence and current Kiwi official Paul Williams.

There is a trade-off between attack and defence in order to produce quicker ball for both sides. The ball-carrier is no longer allowed to make a double movement, or roll on the ground. The defenders have to make a definite attempt to release the ball-carrier, clear the tackle zone and support their own bodyweight in any attempt to make a steal on the ground.

The idea is to generate quicker turnovers for the defence via an immediate ‘lift’ of the ball, or quicker ball for the attack with defenders releasing and clearing out immediately. That is the way it has worked in other competitions globally, like the English Premiership.

Not so in the current series between the Springboks and Lions. Both teams have preferred to kick rather than run, with an average of 62 kicks per game compared to 143 rucks. That ratio of one kick to every two rucks compares unfavourably to the knockout stages of the 2019 World Cup, where the ratio was greater than 1:3.

Between them, the two teams have put together only 10 examples of multi-phase play going beyond six phases of attack in two games – six by the Lions and four by the Springboks. All of those have had starting points within the opposition half of the field.

In the first Test, Nic Berry attempted to encourage attacking play by awarding seven of the ten breakdown penalties to the attack, rather than the defence. In the second, with Kiwi Ben O’Keefe in charge, the trend was reversed. O’Keefe awarded seven penalties to the defence at the breakdown, and only four to the attack.

18 of the 26 clips used by Erasmus focused on events in and around the breakdown. Particular attention was paid to Lions’ illegal entry outside the gate, sealing off, and ‘legitimate’ poaches by the Springbok defenders which were not rewarded. No wonder then, that the Springboks production of turnover penalties increased from a mere one on the first test, to five in the second.

In the process, the new guide-lines at the tackle set out by World Rugby were lost without a trace.

In the first game, Nic Berry followed the guide-lines by requiring the defender to support their own bodyweight at the tackle during the ‘poach’:

This was an instance used by Erasmus in his video. The Bok defender (prop Trevor Nyakane) clearly over-extends, and is not supporting his own bodyweight in the initial stages of the poach:

He only brings his left leg forward to provide that support in the last stage of the steal:

Berry rightly penalised the defence, but in a very similar situation in the second game, the decision was given the other way:

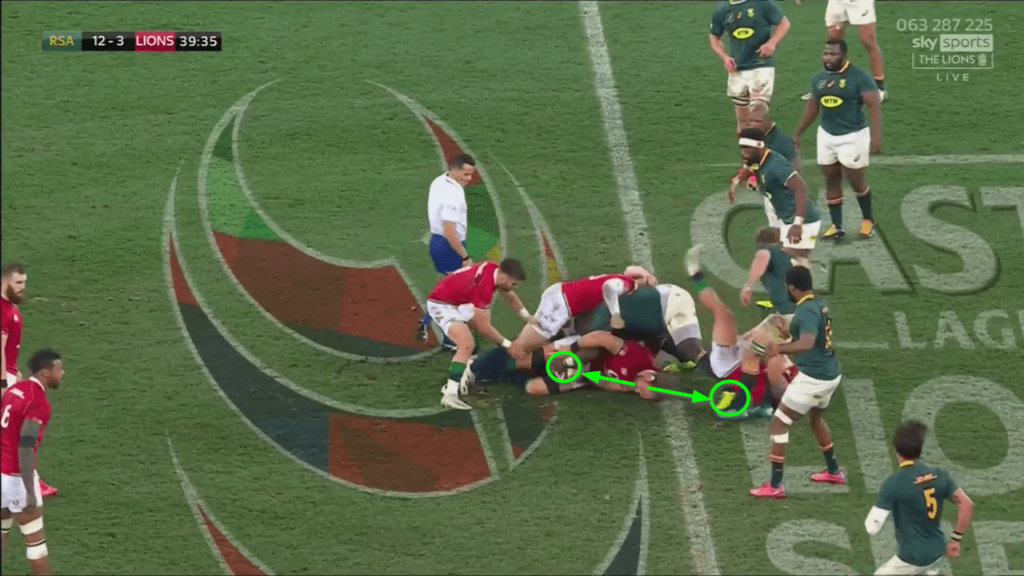

South African hooker Malcolm Marx is on the ball, but he drops a knee on to the floor in order to establish a good position:

Marx loses his feet momentarily, and therefore he should roll out of the contest rather than continuing to compete.

The issue of a clear release of the tackled player by the tackler was never fully resolved by either official. In the first test:

This is an instance where the Lions are trying to play multi-phase attack and move over the six-phase threshold. They are not rewarded for the effort by developing any momentum between two consecutive rucks. Tacklers and assist tacklers are required to show ‘clear release and separation’ from the ball, but that is not forthcoming.

At the first tackle, Marx goes straight down on the tackled player and there is a three-second delay in release. At the second, assist tackler Eben Etzebeth does not show clear separation and the delay is even longer (five seconds). The next phase of attack is already dead in the water.

The refereeing trend in the second match encouraged South Africa to push the envelope even further:

The first instance shows the ideal outcome from the Springboks’ point of view. Two men hard over the ball, with the tackler still sitting in the ‘gate’ and obstructing the approach of the cleanout support players:

The assist tackler, Makazole Mapimpi, does not show a clear release, while the primary tackler, Lukhanyo Am, forces the Lions support players to take the long way round into the cleanout:

“Tacklers must not impede attacker’s ability to clean out. If they fall between the ball and the attack – they take all responsibility to get out. If they can’t, they will be PK’d. To reward a jackler the tackler must not impede the cleanout. Dealing with the tackler is first priority.”

It is no wonder that the series has produced so little constructive multi-phase rugby, when the 2020 guide-lines are so regularly ignored:

Once again, two consecutive phases of attack. Firstly, Springbok number 9 Faf de Klerk fires right over the top of the tackle off his feet, and that means a five-second delay in release. Then, prop Steven Kitshoff sticks to the tackled player like glue, and another slow ball leaves the kick by Conor Murray as the only viable option.

If the evidence of the first two test matches in South Africa is a reliable guide, the game is not more fluid and dynamic than it was in the knockout stages of the 2019 World Cup – quite the opposite. There is more kicking, less running and passing, and fewer rucks built. Ball winning has become more important than ball using.

Until a strict and clear protocol is established at the tackle area, with tacklers showing a clear release and roll out, and poachers actually trying to stay on their feet and lift the ball immediately, matters will not improve. Given Rassie Erasmus’ very public video presentation before the second test, World Rugby needs to demonstrate that it really means what it says, and back up words with action.

Hi Nick, good piece. Just remembering the rules under which I played rugby in the sixties and seventies. If any part of the body from the knee up touched the ground the ball carried had to let the ball go. Not pass of play it in any way. The cardinal sin was "dying with the ball" which meant that you got rid of the ball before you got tackled or you stood in the tackle and popped. The guys with low center of gravity and strong legs were at an advantage (players like John Gainsford Bok centre of the sixties). In my opinion that led to much more fluid and exciting play. The concept of going to ground and playing the ball seemed to me to try to echo rugby league, but the problem was that rugby was based on a fair contest for the ball and so the tackle/ruck laws came into play. Quite frankly I think reffing the tackle/ruck laws are like walking through a minefield. Sometimes the tackler gets his hands on the ball but is prevented from picking it up cleanly then he is in danger of being beaten by the ruck and having hands in. The line between tackle/release/hands in is so fine it's virtually impossible to get two different refs who see it exactly the same way. Personally I believe rugby would be more fluid if we went back to not being allowed to play the ball on the ground.