Since Australian attack coach Scott Wisemantel left the England setup following their 2019 Rugby World Cup campaign, England haven’t yet found the same rhythm in attack that they seemed to possess that season.

It was common for England to explode out of the blocks and land a set-piece try within the opening five minute period of a test match, such was the prowess of their in-tune attack.

Their power players blended perfectly with their speed and skill players to execute nearly everything to perfection early in games. Their statement win against defending Grand Slam champions Ireland in Dublin to start the 2019 Six Nations put the world on notice that they were a force to be reckoned with.

England did not have the current attacking continuity issues during Wisemantel’s tenure with the team, perhaps indicating his importance to the set-up.

In the loss to Wales, England showed lots of promise but lacked the killer instinct. The polish is not quite there, leading to questionable decision-making and problems with consistent execution.

The timing of many lines are off, players’ depth is not quite right and they aren’t reading each other well. The option-taking is often less than desirable as a result. They’re not taking the worst option, just often not the best one.

With the likes of Billy Vunipola in the backfield to field kicks, England often had great transition platforms to attack from in this game but failed to take advantage of all of them.

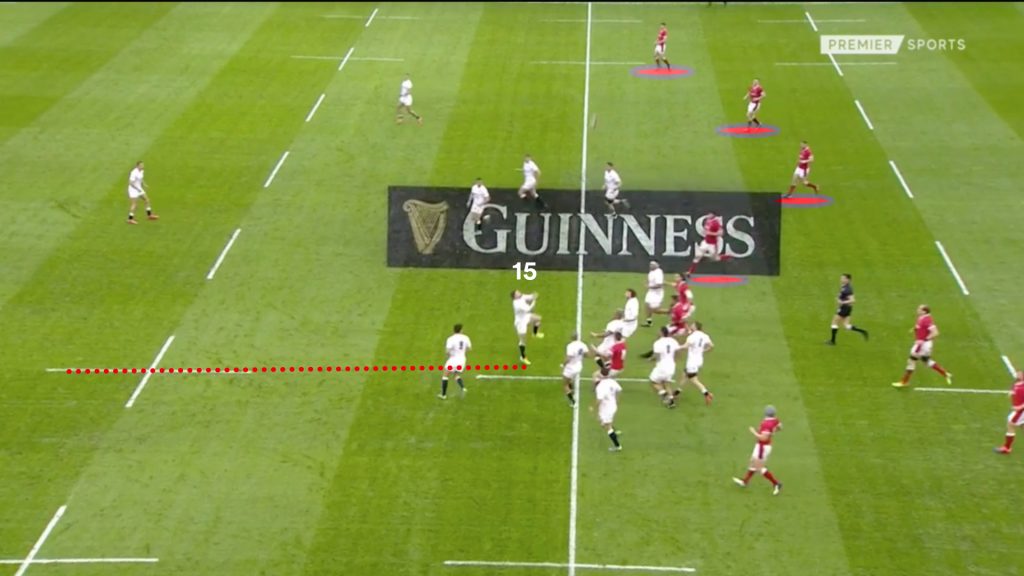

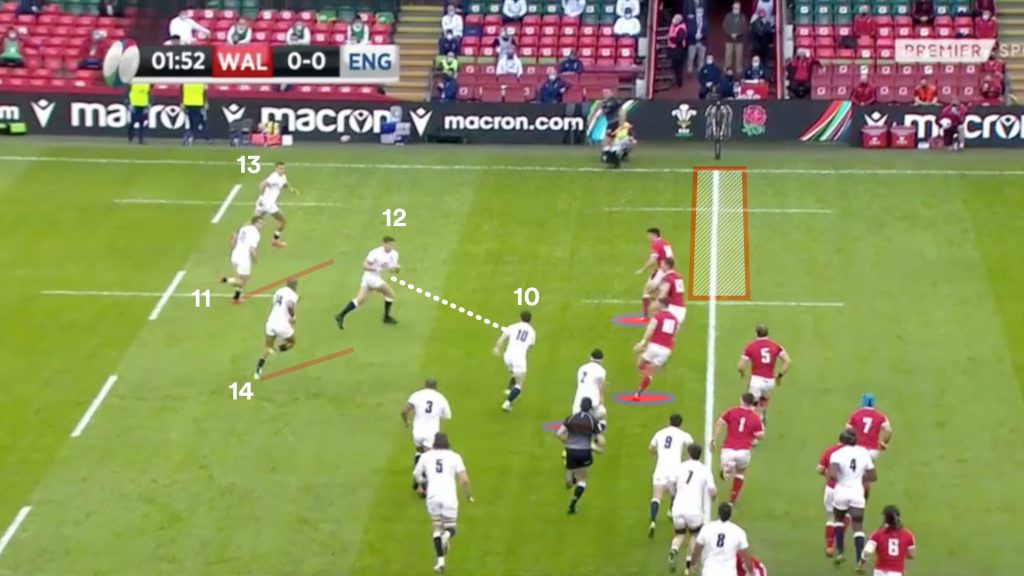

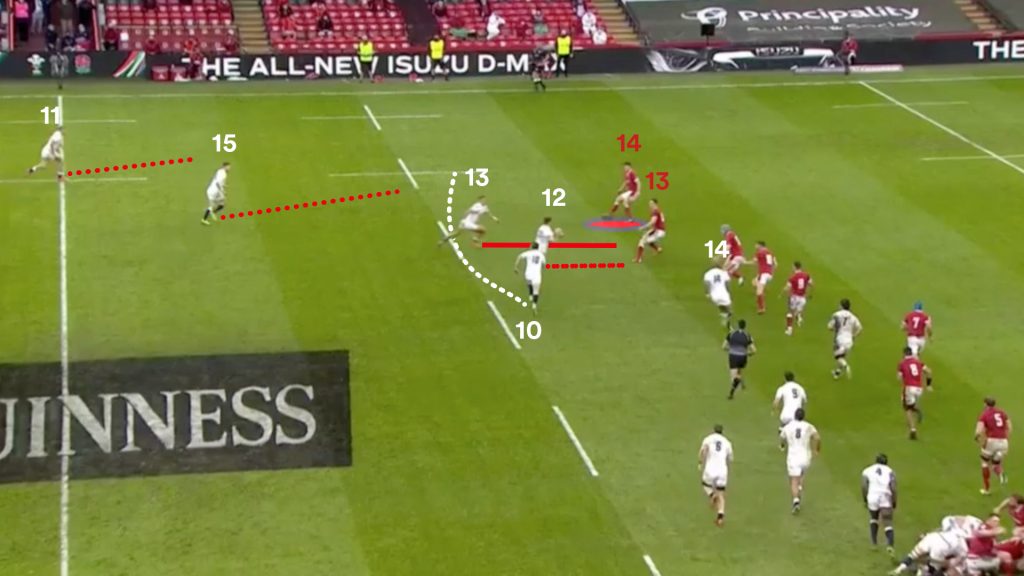

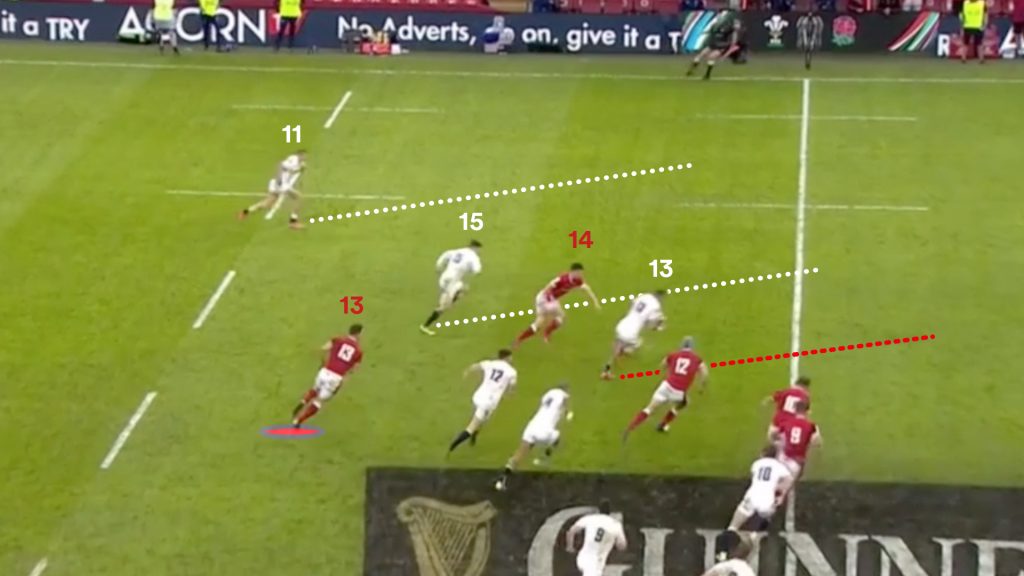

Early in the match, Elliot Daly fields a high ball and sets up an opportunity to attack to the left during a kick transition window, where Wales are manned by just four widely-spaced defenders.

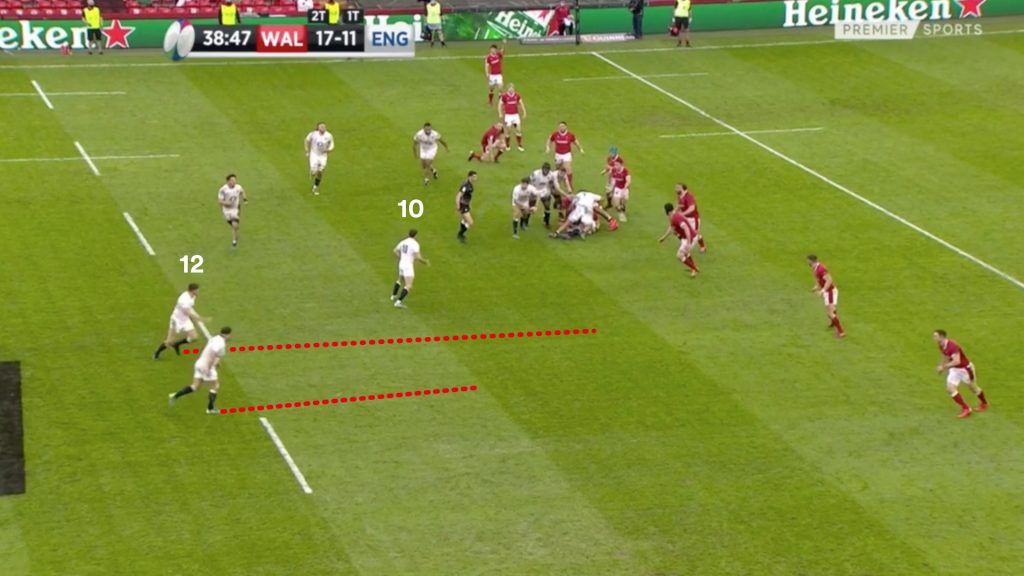

England have employed a roaming tactic with Jonny May (11), who is seen below off his wing tracking Owen Farrell (12) as an option off either shoulder. This is done with a desire to get May as many touches as possible but can create problems later as we will see.

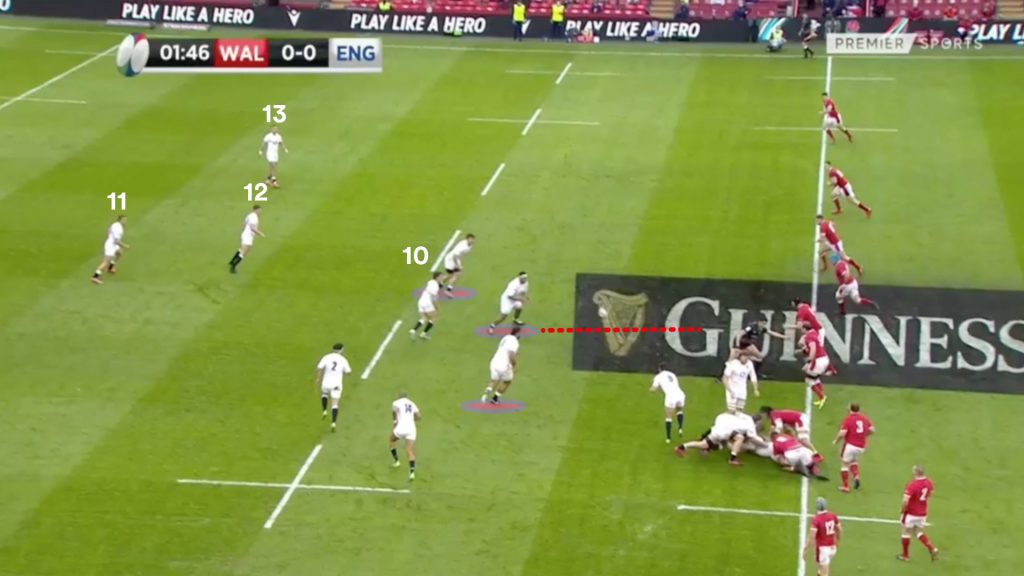

On the first phase after the kick receipt, England aren’t completely ready to attack wide directly. Farrell (12) is too deep and with May behind him, England aren’t stretching the field as they have no one out beyond centre Henry Slade.

One option is a backdoor pass to Ford, who could feed Farrell to link wide, but the depth at which England are set up would make it easy for Wales to cover.

The Welsh defence is a classic drift defence and with the speed of a guy like Louis Rees-Zammit on the edge, they are happy to show you to the sideline where he can run you down.

If you are too deep, Wales have time to wait, bring inside support and push the ball to the touch line. That’s exactly what they want.

If the space between the edge defenders is to be punctured, England need to freeze Dan Biggar above, leaving just George North and Rees-Zammit outside him.

Biggar can be seen biting down on the support line of Curry above so England already had this in motion. To exploit this, they need to be flat and pressing outside of him so he can’t recover.

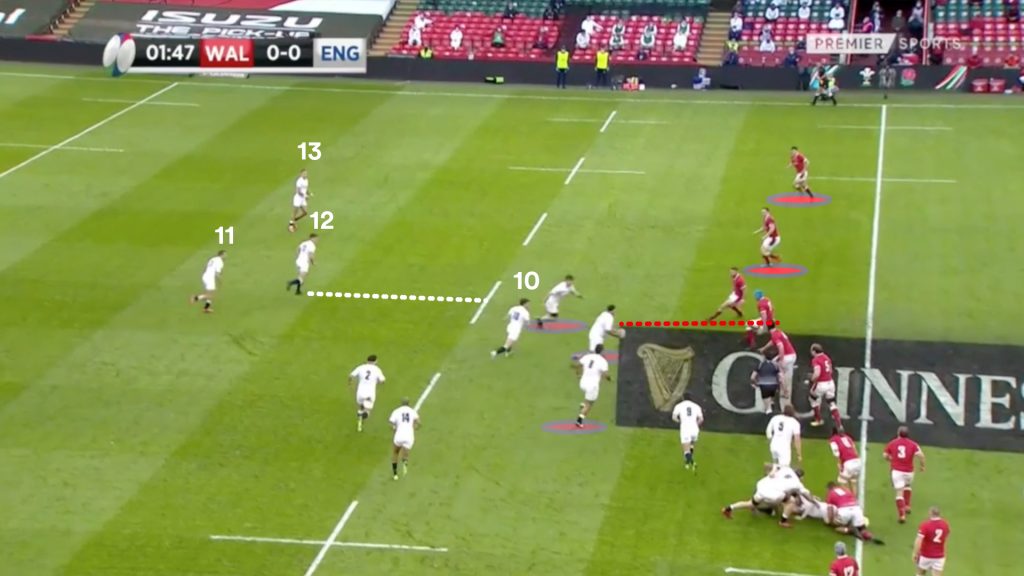

If May was properly on his wing and Farrell was flatter, England would have a comfortable 3-on-2 situation with Biggar beat. Instead they carry. It’s not the worst option but doesn’t hit Wales where they are compromised.

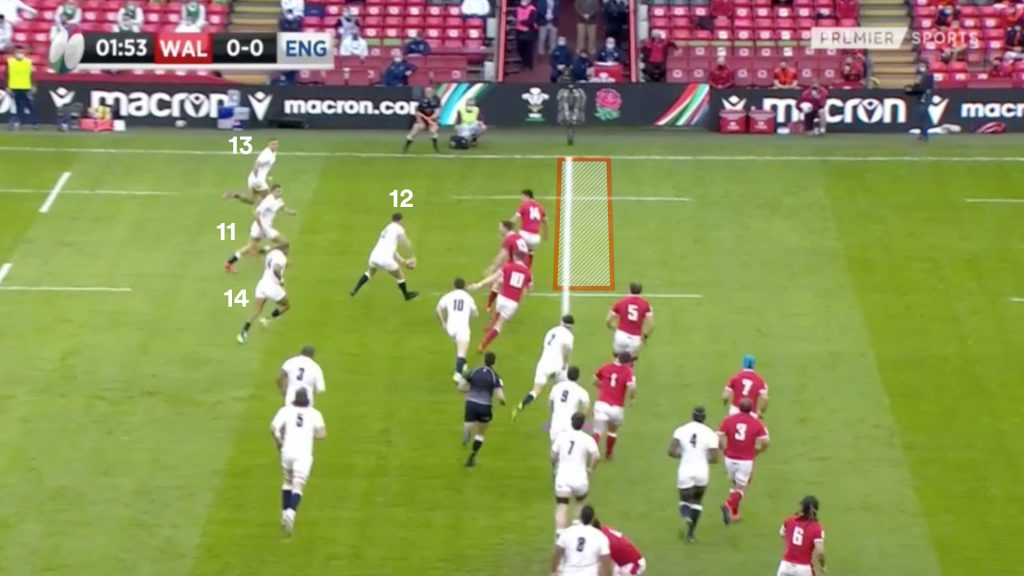

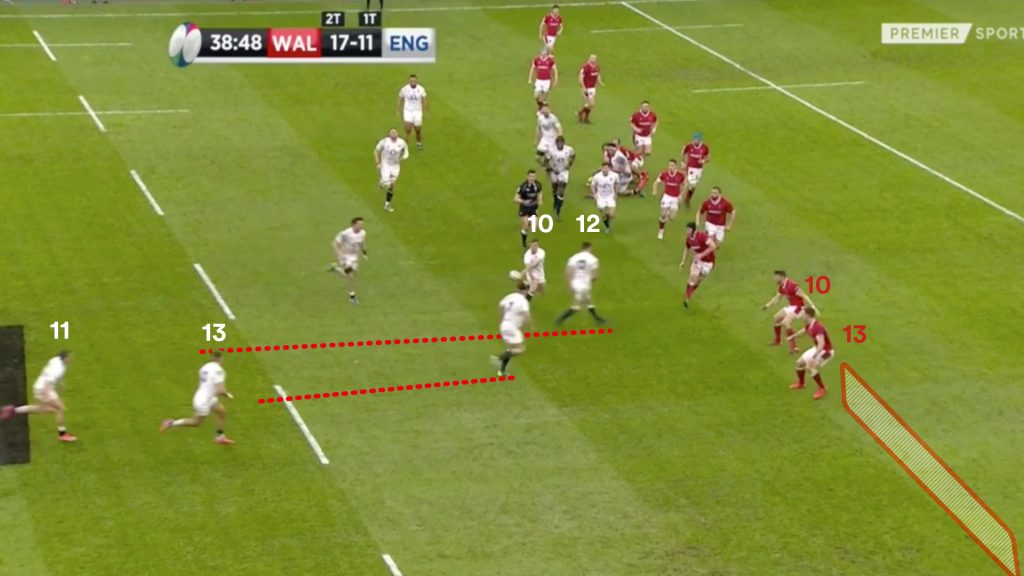

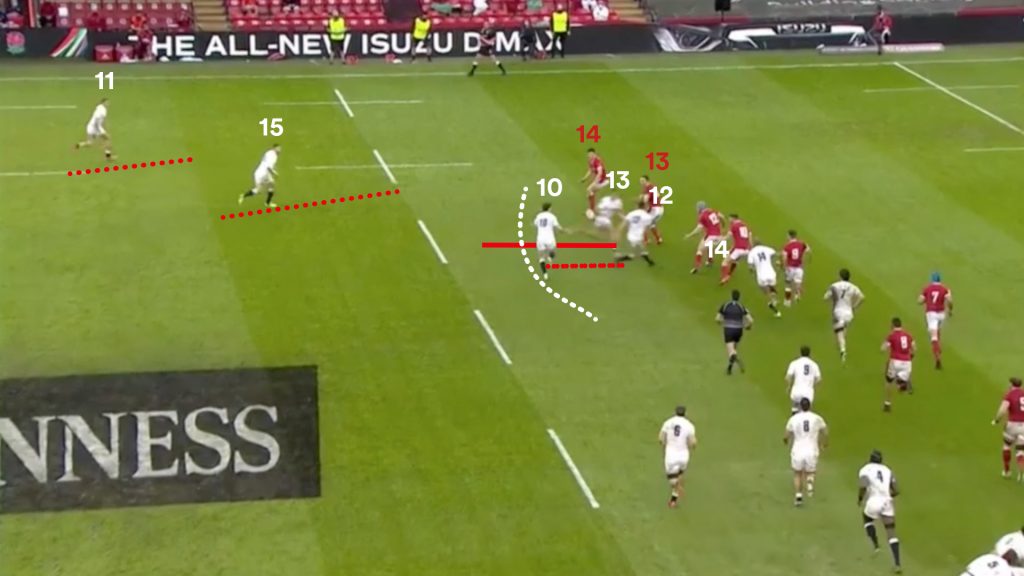

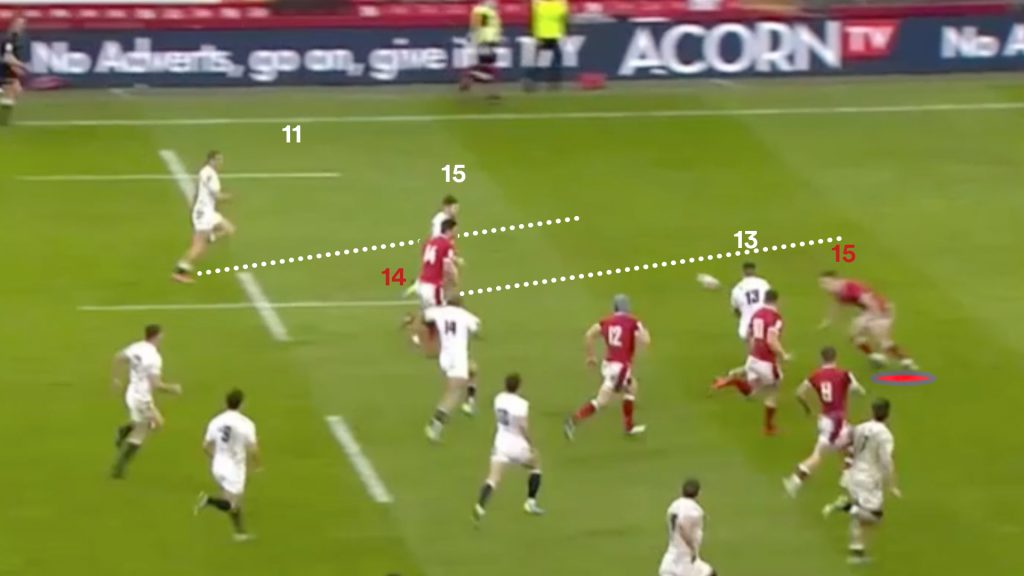

By the next phase, England have the Ford-Farrell axis set while Anthony Watson (14) has worked hard to offer an inside option off Farrell (12) for a set play.

This is where Jonny May’s positioning really becomes redundant. He’s looking for work around Farrell but ultimately the best place he could be is on the wing. England have the full 15-metre tramline free but no one out there to stretch Wales’ defence.

May ends up injecting outside Farrell and playing outside centre. This is where it gets illogical, as England end up with wing Jonny May playing centre and centre Henry Slade playing wing. Ideally, in this exact situation you want the opposite.

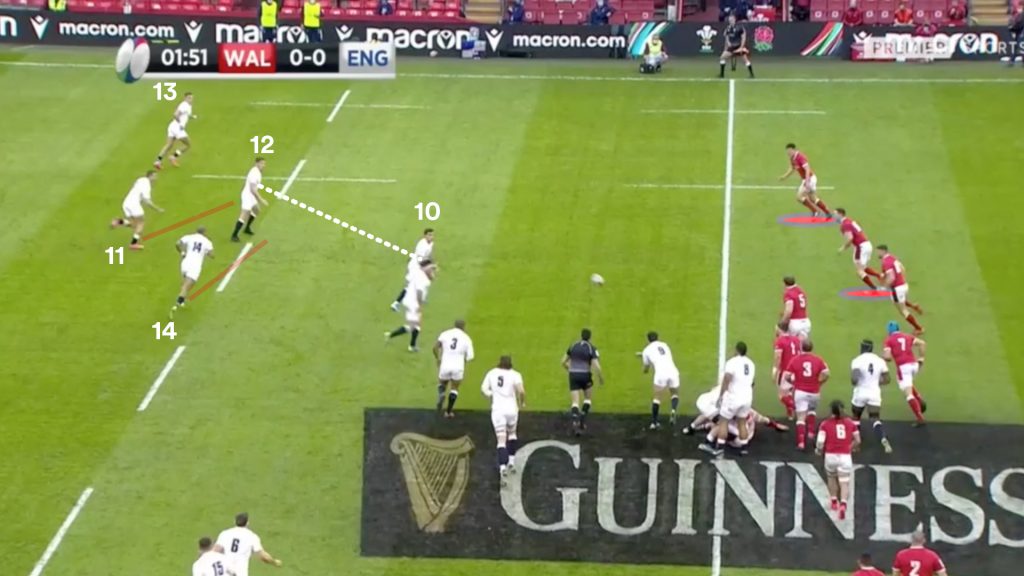

With two players outside him, Farrell offers early ball to May in the hope that he will commit Rees-Zammit and play Slade down the sideline. So he defers the playmaking responsibility to May, a run-first wing who doesn’t have the passing game of Farrell or Slade.

If Slade and May were reversed, there is a high likelihood May is streaking down the left hand side with Anthony Watson (14) looming up on his inside for a try-scoring opportunity.

Instead, May tucks, runs and is tackled and pilfered by the arriving George North and Wales earn a turnover penalty.

England want to get both wingers involved around all areas of the park but it is leading to inefficiency in their attack, with running lines that don’t really challenge anyone and asking players to perform roles that others are better placed to do.

There is a clunkiness to England’s attack that needs to be ironed out with better clarity on what they are actually trying to do. On top of that, some of the option-taking and execution has to be better.

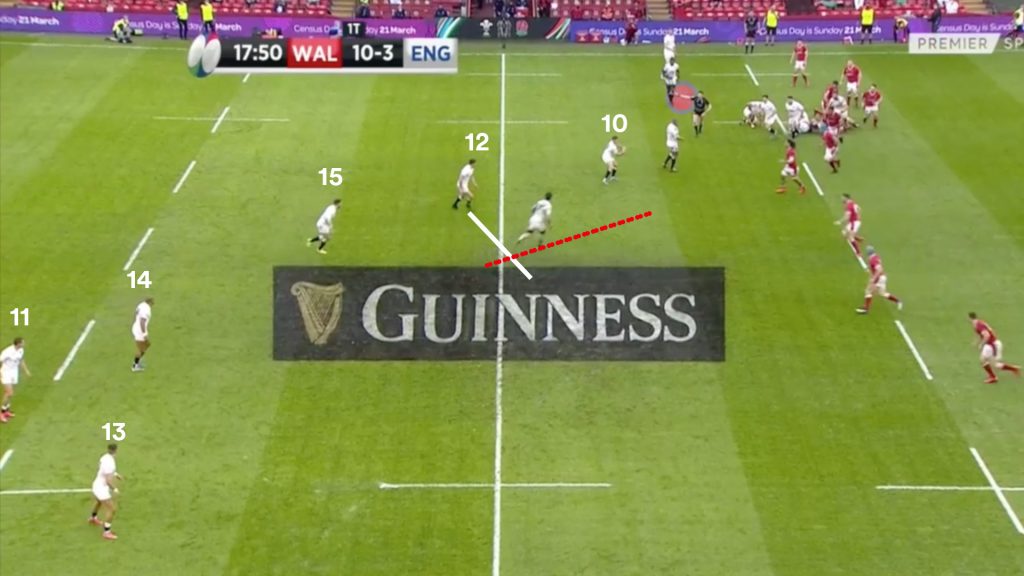

After fielding a kick, Billy Vunipola had a strong carry that setup England in prime position to attack again on first phase in this transition window. Wales concede a penalty advantage by not rolling away fast enough so England have a free roll of the dice.

They have the penalty advantage and a large open side set up with a full compliment of backs. Both wingers this time position inside of Henry Slade (13), pushing him to the right wing position.

England run a screen with Ford playing distributor to Farrell who inadvertently kicks it away downfield looking for the touchline.

It is a great kick, landing a few metres from the try line and finding touch inside the five metre line. But the question is, why?

It is a free play with penalty advantage, in a great attacking zone with the opposition needing to set a defence following a kick. There is no downside with all the upside. At minimum, a contested kick could offer a favourable bounce, or using the compliment of backs to attack the space could spark a break.

The intent to use the ball when their is a risk-free play on offer was not there by England’s captain. Although it was a one-off decision, in test rugby you never want to leave opportunities on the table and is symptomatic of a side not thinking clearly.

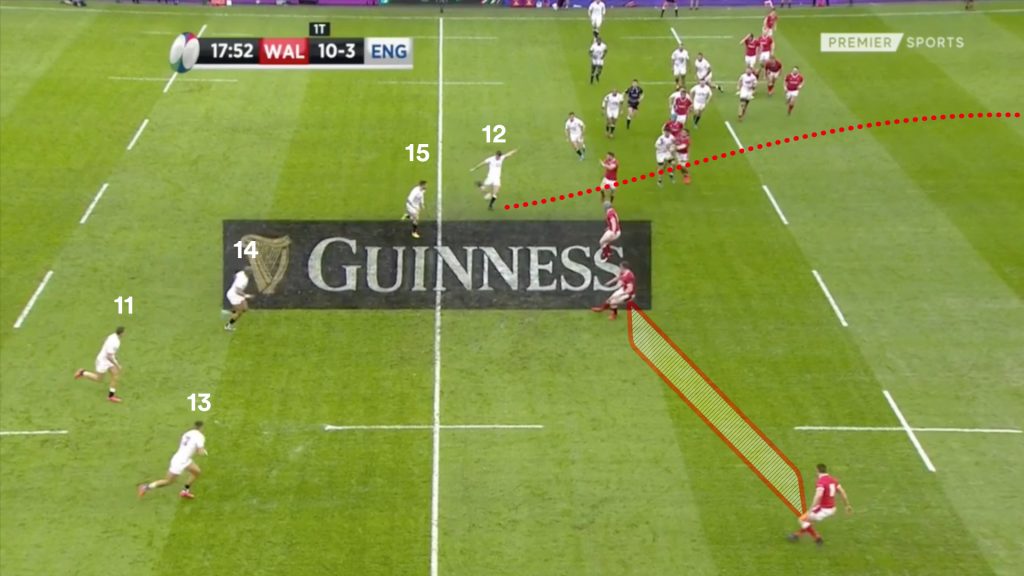

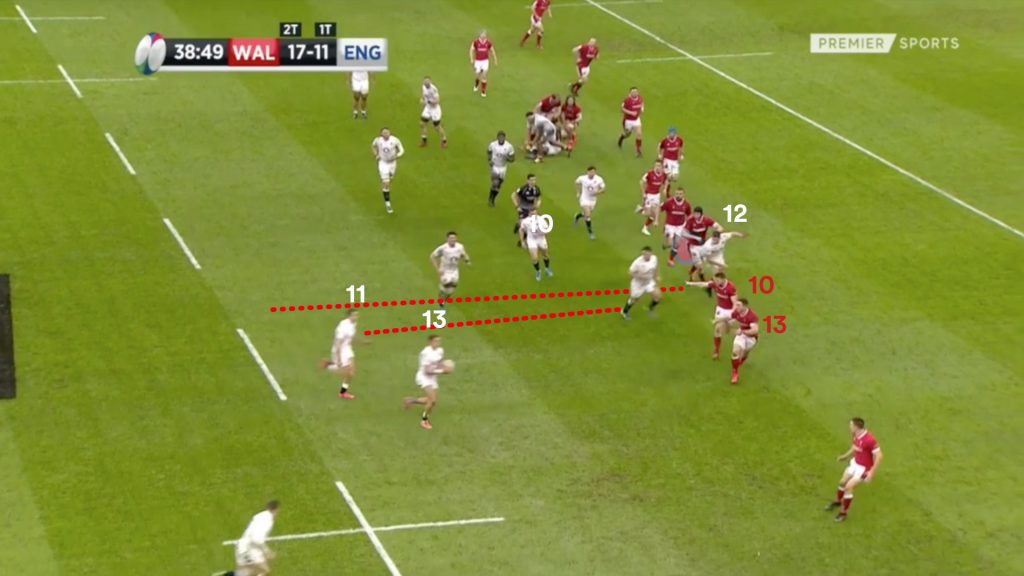

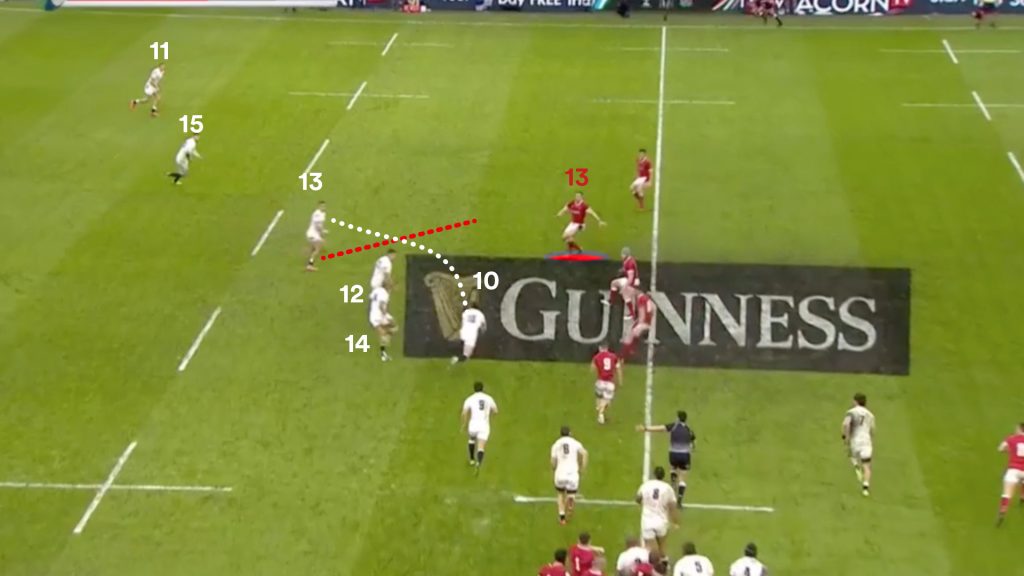

Another Billy Vunipola kick return set up another open side opportunity where England tried to inject Jonny May again off his wing. This time they fake the Ford-Farrell connection and whip it out the back to Henry Slade (13).

Again we see Jonny May hanging off another playmaker, this time Slade, looking for an opportunity in traffic. The dummy line by Farrell (12) opens up a gap for May by creating separation in the line through incidental contact.

With the Welsh line playing drift defence, a collision with an inside defender stops that man from drifting in sync, creating a growing gap.

Farrell’s collision does that, and creates a window for Slade and May to exploit. By squaring up Biggar, Slade could play May into the gap but the option isn’t considered this time.

Just like Farrell on the first opportunity, Slade gives his outside man early ball, deflecting the playmaking duties to Elliot Daly.

Daly needs to be the playmaker to create the break. He can’t get Adams to commit and the Wales drift defence swallows up England again with North sliding to make the cover tackle.

Liam Williams strikes at the breakdown after Daly is tackled and Wales get another steal at the optimal moment.

In all these transition examples, England lacked a ball-player to commit a defender at the line when required. Wales were happy to drift and force England to the edge and then win the battle on the ground by competing hard, while England’s distributors were happy to play early and defer to the outside men who couldn’t draw anyone.

Credit has to be given to the Welsh outside backs for sticking to their system and playing good shadow defence. For most of the day, they conceded metres instead of breaks and ‘won’ these battles despite being disadvantaged by numbers.

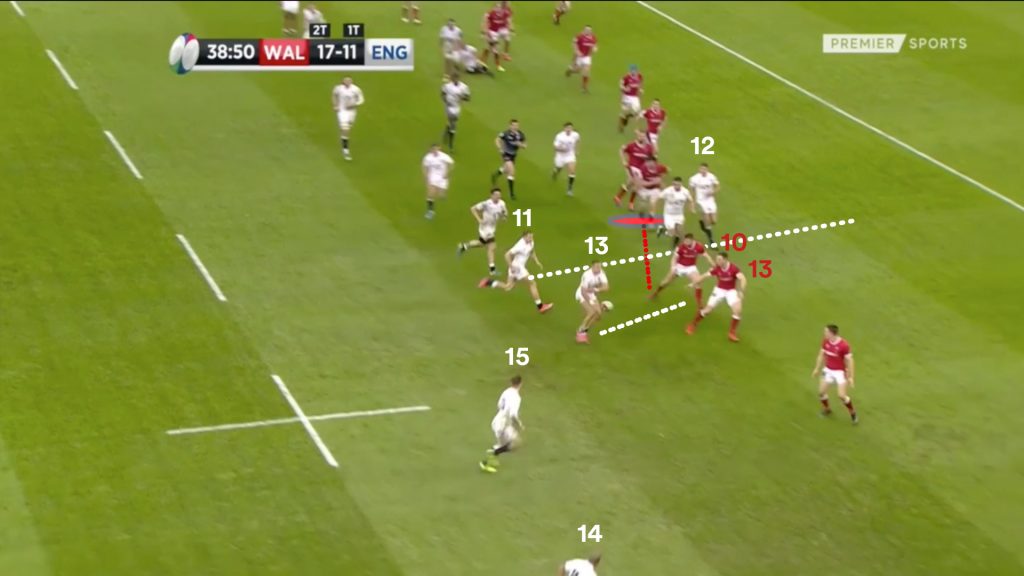

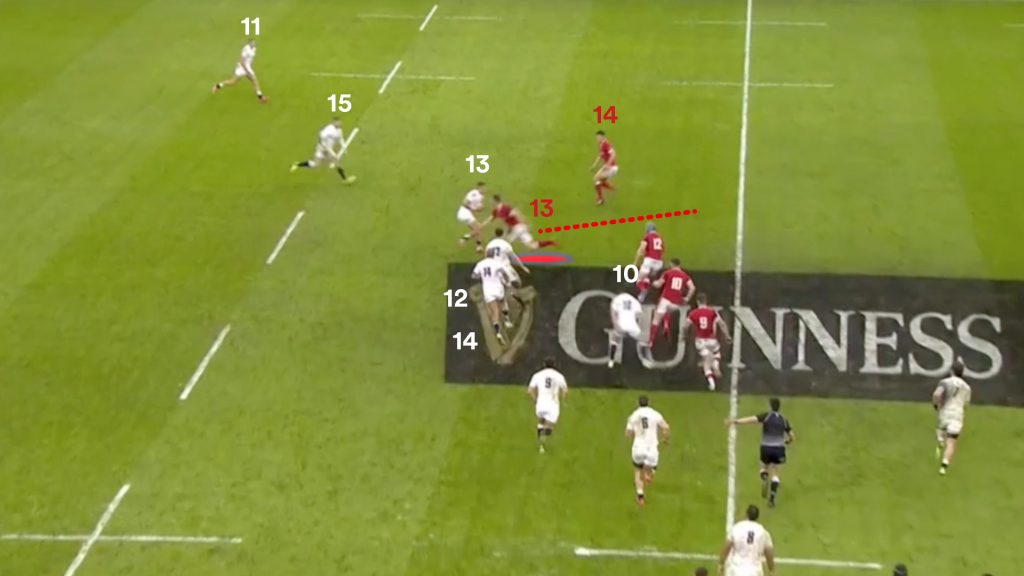

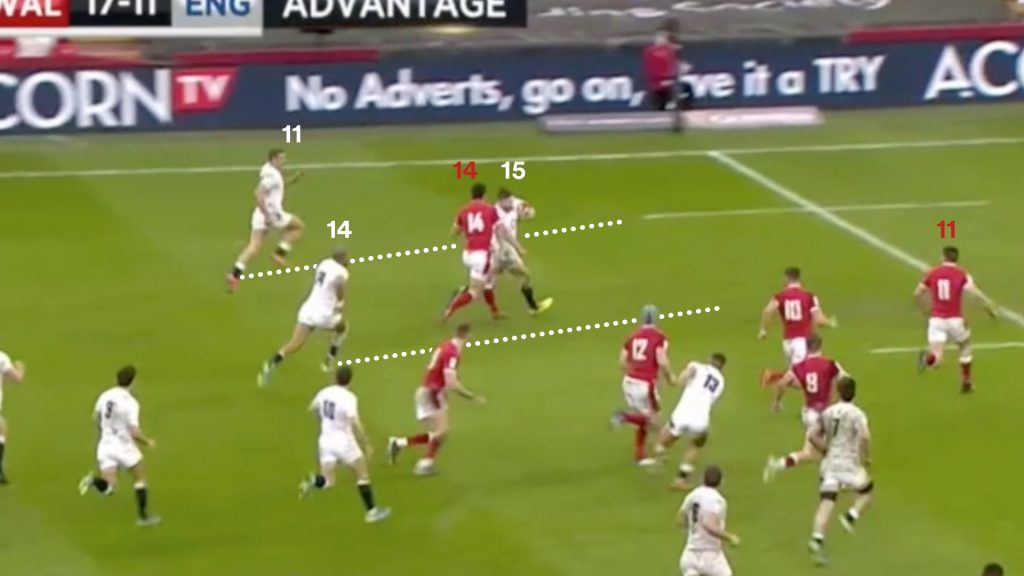

Later in the half from a set-piece scrum, England went about attacking the new combination of George North at outside centre and young wing Louis Rees-Zammit. Here they run a wrap play to overload the far side to try and isolate Rees-Zammit (14).

England used blind winger Anthony Watson (14) as first receiver to extend some width to the play, in order to get George Ford (10) around the edge on a pullback pass from Owen Farrell (12).

Wales want to use their jockey/drift defence to shut this play down, and centre George North already has his hips turned facing the sideline looking to push out. He’s passed Henry Slade (13) already, and would not be able to stop the England centre running hard against the grain.

Playing Slade (13) short could have been a good option for Owen Farrell (12) instead of the pullback pass to Ford.

If he squared up and committed Jonathan Davies, a short ball to Slade on the burst would expose North’s eagerness to jockey too early.

Instead, North is free to jam Ford coming around the corner. The flyhalf does get away a perfect pass to create a 2-on-1 on the edge but Elliot Daly drops the ball cold with Jonny May free outside him.

England had two options to cut Wales open (Jonny May and Henry Slade) but failed on both counts to put Wales’ defence under pressure.

On the final scrum play of the half, they do finally break through George North’s channel with a brilliant ‘miss 2’ pass by Ford that beats the outstretched hands of the Welsh centurian.

Slade slips through into the backfield and England have a chance to capitalise on the break and make Wales pay. With two players to the outside, he forces fullback Liam Williams to commit and gets the ball to the closest man Elliot Daly.

Although Rees-Zammit might be the fastest man on the pitch, Elliot Daly has the upper hand and the leverage here.

Pursuing from behind, Rees-Zammit can take the man but has low odds of stopping the ball from getting to Jonny May on the outside.

Daly has to commit Rees-Zammit and find Jonny May on the outside, or he can provide early ball and stay alive as inside support. Instead, he dies with the ball by trying to fend Rees-Zammit off one-on-one.

The only man who could have stopped Jonny May who Liam Williams out of the picture is the last-ditch cover line of Josh Adams.

It is a one-on-one footrace, but May has scored tries from far more improbable situations over the last 12 months. It is an opportunity that you want to give him that England didn’t.

Anthony Watson has again worked his way upfield to offer support on the inside and could offer an inside passing option should Adams make the ground needed.

It’s not the worst option in the world by Daly as England still have Wales on the back foot and scrambling to reset the defence. They end up scoring three points shortly after to end the half but the killer instinct to score the try from the break was missing.

This is England’s attack in a nutshell at the moment. They either struggle to execute completely through a turnover or error or, on the rare occasion they do execute, can’t find the finishing touch.

England’s sole try of the first half to Anthony Watson was mainly down to the brilliance of the winger himself. The launch pattern did not find great momentum, with Farrell getting held up on a first phase crash run and forward runners overshooting Ben Youngs around the corner on the second. It quickly became disjointed, but persistence paid off with the finishing talent of Watson.

They aren’t playing to their potential at the moment with ball-in-hand and the attack appears to have chemistry issues. The talent is there but they don’t look like they are on the same page, with the finer details missing and execution often letting them down.

It has to be said that the ill-discipline is a major factor hampering their attacking game due to constantly giving the opposition the ball and territory. The penalty counts are hemming Engand’s ability to find a rhythm and apply pressure.

Despite having calls go against them, England had their chances in the first half to take control of the match. In the second half the game slipped away due to ill-discipline.

England have been in a slump like this before under Eddie Jones, with a historic 5th-place finish in the 2018 Six Nations. That dismal tournament is what led to Scott Wisemantel being brought into the coaching set-up in the first place, and Jones wrung the changes bringing in a new host of players like Tom Curry as the old established guard was moved out.

The final two games against France and Ireland will tell a lot, and if the end result is similar to 2018’s tournament you would have to expect a similar response. A regeneration of the squad can’t be too far away.

More analysis from Ben Smith

If you’ve enjoyed this article, please share it with friends or on social media. We rely solely on new subscribers to fund high-quality journalism and appreciate you sharing this so we can continue to grow, produce more quality content and support our writers.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free