Rassie Erasmus remains the biggest threat to the British & Irish Lions’ ambition of an unbeaten run through the southern hemisphere. The architect behind the South African rugby revival – which culminated in the Springboks winning the 2019 World Cup – continues to apply his forensic eye for detail as well as his considerable emotional intelligence to the task of uniting a crack team of players and coaches under one banner.

Erasmus has been described as a genius after boosting South Africa from seventh to first in the World Rugby rankings and for tackling the prickly yet important issue of transformation with an unprecedented sense of transparency and dignity.

This word ‘genius’ doesn’t do his talents or his insatiable appetite for work and reward justice, though. Few can see the game as it is – and perhaps how it could be in the short and long term – with such piercing clarity.

This isn’t just the opinion of a writer who has followed Erasmus closely since his days of innovation at the Cheetahs, the Stormers, Munster and finally the Boks, nor a view held exclusively by current players and coaches within a much-improved South African system.

Indeed, some might view Nick Mallett – the Springbok coach who presided over South Africa’s first Tri-Nations title success as well as a 17-Test winning streak – as a master of the coaching craft with a superior understanding of the game.

So when Mallett describes Erasmus as a genius, and goes on to unpack why, one begins to understand exactly who the South African team have in their corner, and why the Lions would do well to respect his power and influence.

To understand Erasmus the coach, one first has to understand Erasmus the player. In the mid-1990s, team-mates called the young flanker ‘Square Eyes’ because he spent hours and hours in the team room, poring over video clips of the opposition.

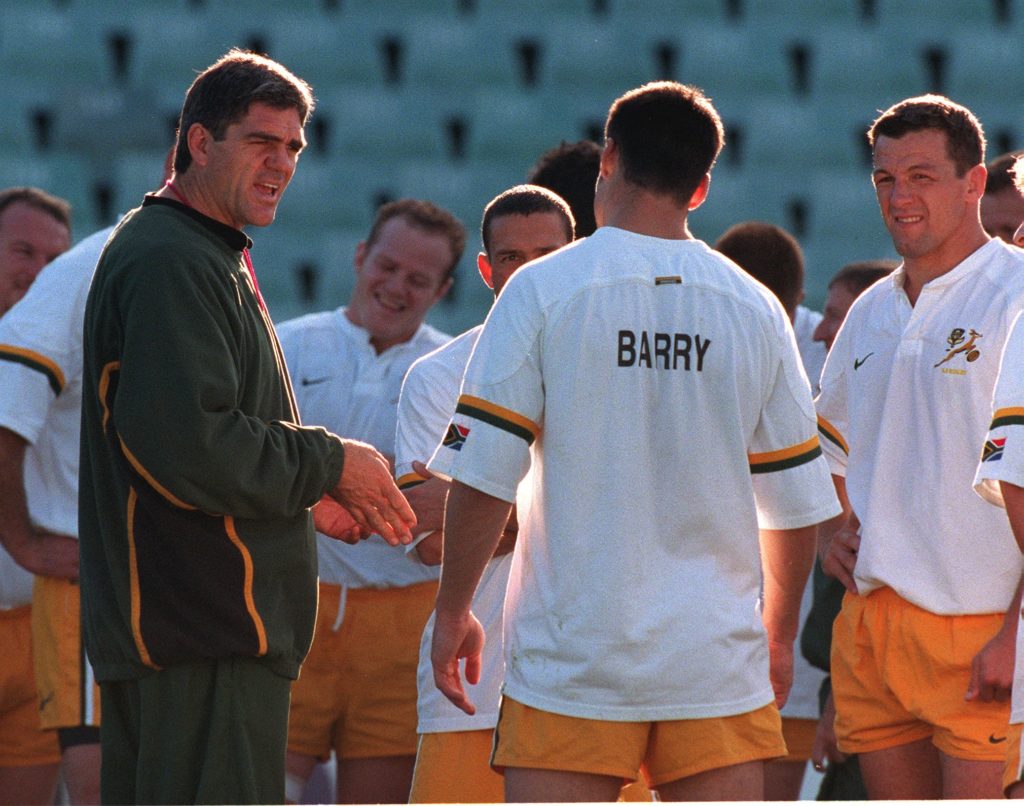

Erasmus made his debut in the third Test against the Lions in 1997. The Boks won that fixture at Ellis Park to lend the series scoreline some respectability. Later, after coach Carel du Plessis was sacked, Mallett assumed the reins and set about steering the team in a different direction. Mallett was in charge for 16 games during the Boks’ record-equalling run between 1997 and 1998. As a former Springbok loose-forward, he recognised that South Africa had something different in Erasmus – and proceeded to back him to start in 15 of those 16 matches.

“I watched him closely as he was coming through the ranks at Free State,” Mallett tells The XV. “He reminded me a lot of Rob Louw (who played for the Boks and WP in the 1980s), a forward with great hands who almost served as an extra back; a player who could lend his side great continuity.

He’s the first player I know of who asked the coaches for clips of the opposition. He wanted to do his own analysis, to identify the threats and the possible opportunities.

Nick Mallett

“He was never what you would term a fetcher. He was just very clever and maximised what talent he had. Somehow he got to the ball quicker than anyone else. It wasn’t because he was the fastest; it was down to his anticipation.

“When I got the Springbok job, I looked at those strengths and decided that he embodied the style that we wanted to play.”

South Africa have never wanted for good loose-forward options. In the mid-to-late 1990s, however, there were some especially impressive candidates vying for those three positions. A few of these players would go on to lead the Boks in later years.

“Andrew Aitken was pushing for a place in the back row,” Mallett remembers. “Bob Skinstad was coming through, while Corné Krige was also developing nicely. I just felt that Rassie was a very special player and person, which is why I picked him whenever he was available.

“He’s the first player I know of who asked the coaches for clips of the opposition. He wanted to do his own analysis, to identify the threats and the possible opportunities.”

Mallett describes an episode that culminated in a new level of respect for Erasmus. In the week leading up to a Test against Australia in the 2000 Tri-Nations, the player approached the coach with an idea. The Wallabies, at that stage, were the best side in the world.

“He wanted to talk to me about the Wallabies’ exit strategy. That conversation alone – the fact that he was thinking about such things – set him apart,” says Mallett.

Erasmus had noticed that the Wallabies ran a move from the lineout that resulted in John Eales hitting it up and then Toutai Kefu shaping to take the pass at the next phase. Scrum-half George Gregan then proceeded to throw the ball behind Kefu’s back, to either Stephen Larkham or Chris Latham, depending on whether the Wallabies required a right- or left-footed kicker for the clearance.

“I was impressed that he’d seen that. I told him that we would apply the necessary pressure on those receivers through our loose-forwards,” adds Mallett. Erasmus had done his homework, however, and was one step ahead of his coach. “He told me that he’d seen the move used several times by the Wallabies in previous games. While there were subtle variations, the one constant was that Gregan never played Kefu on that short ball.

“Rassie was set to mark Kefu in that instance. He proposed, however, that he go for the intercept instead. And on the day, he did exactly that.

“Gregan threw the ball behind Kefu’s back, and Rassie picked it off. He ran 20 metres and dived over the line. At the same time, however, the Wallabies players dived on top of him and so neither the referee nor the TMO had a clear view of the grounding. The try wasn’t awarded and we lost the game by one point.

“That piece of analysis and execution by Rassie has always stuck with me, though.”

Erasmus struggled with injuries in later years. A broken foot led to his first coaching opportunity in 2004. Instead of focusing solely on his recovery, he pushed for a chance to work with the coaches of Free State’s Vodacom Cup team.

One thing led to another and, by 2006, he had coached the senior Free State side to two Currie Cup titles – the latter being shared with the Blue Bulls. While the Cheetahs battled in the Super Rugby competition, Erasmus’s bold and innovative methods attracted attention. Jake White appointed Erasmus as the Boks’ technical advisor ahead of the 2007 World Cup.

One of these methods involved Erasmus standing on top of the roof of the Free State Stadium, using coloured paddles and lights to signal his players. It was widely criticised and some went as far as to address the coach by a new nickname, ‘DJ Rassie’. To be fair, Mallett himself took some time to appreciate what Erasmus was up to.

He prepared his charges for every eventuality. That wasn’t a coach looking to control his players but empower them through knowledge.

Nick Mallett

“I was a bit amused when I saw him standing up there for the first time. My initial impression was that the method was about maintaining absolute control,” says Mallett.

“But Rassie had done so much analysis on the opposition and it was ultimately a means of communicating with his players about what the other team were likely to do in a particular situation. Once his players had that information, the onus was on them to execute.

“Again, his attention for detail was incredible during his stints at the Cheetahs and the Stormers. He’d crack the lineout calls of every opposition team. He prepared his charges for every eventuality. That wasn’t a coach looking to control his players but empower them through knowledge.”

His career appeared to fizzle out after he quit his director of rugby position at the Stormers in early 2012. The battle between the professional arm of the franchise and the amateur clubs – which continues to compromise the Stormers today – proved a drain on his time and energy. Dealing with the Cape media also took its toll.

SA Rugby seized on the opportunity to offer him a position as high-performance manager. Erasmus was given the chance to oversee a number of teams and initiatives without concerning himself with the day-to-day grind of coaching.

“He had a great understanding of the bigger picture,” says Mallett. “That’s what you need in a high-performance manager or a director of rugby.”

Apart from his day-to-day responsibilities, Erasmus spent six to eight hours a day watching and analysing rugby matches. The desire to innovate, and ultimately to serve the game and his country, wouldn’t allow him to sleep.

“He did so much for rugby in South Africa,” says Mallett. “He put an identification programme into place to monitor players from Under-16 level upwards. That was so important in identifying and nurturing black players and helping SA Rugby to realise their transformation goals at the higher levels.”

Erasmus worked with the Boks as a consultant during this time. In 2016, he got back into coaching via a position with Irish club Munster. Living in Limerick, and exposing himself to a different culture and rugby system, boosted his development significantly.

“Looking back, it was the best thing he could have done,” says Mallett. “As a player and a coach in South Africa, he’d gone from living in a small town in Despatch to playing for the Cheetahs in another small town in Bloemfontein to working with the Stormers in Durbanville. Rassie now had the chance to separate himself from South African rugby and from South African players for the first time.

The players were hurting after losing such an inspirational figure. The way Rassie responded in that situation was nothing short of fantastic. It was a big emotional test.

Nick Mallett

“Moving to Ireland was a big step in his personal development as well as his rugby education. He worked alongside Axel Foley, and when Foley tragically passed away, the fallout in that tight-knit Munster community was massive.

“The players were hurting after losing such an inspirational figure. The way Rassie responded in that situation was nothing short of fantastic. It was a big emotional test. He then took on the job of head coach and did an admirable job.”

His biggest test, of course, was yet to come. After enjoying some success at Munster, he decided to move back to South Africa and rescue a side that had become the laughing stock of world rugby.

Neutral observers – and even some within the Munster set-up – described the move as “crazy”, given that Erasmus and his long-time lieutenant Jacques Nienaber were trading a thriving team in Ireland for a side plagued by various ails in South Africa.

Erasmus, however, never wavered in his belief that he could make a positive impact on the Boks and on the South African system as a whole.

When I had the chance to interview him after his appointment in 2018, he spoke boldly about his desire to beat the All Blacks and to win the 2019 World Cup. The obvious follow-up question to each statement was ‘How?’

Erasmus was adamant that South Africa had the best players in the world. Transformation? It could be a catalyst for success and not – as many people continue to see it – a handicap. There was something else about Erasmus upon his return. Mallett noticed that the coach had acquired a new skill-set.

“He’d always had the technical and tactical coaching gifts. When he came back, however, he had the emotional intelligence to complement those strengths. That’s what the stint at Munster gave to him,” says Mallett.

From the outset, Erasmus looked at transformation in South African rugby and said it was not the problem some people had made it out to be. He said that there were enough black players to make the Bok side on merit, and then made a point of changing the attitude towards transformation within the team. It was a priority and something to be discussed openly.

“That wasn’t the case in the past,” says Mallett. “He got that right, he picked Siya Kolisi to lead the side and he picked the most transformed team [with six black players in the starting XV] in history to play England in the first Test of the series.

“That was a statement, because it was a massively important game in the context of his career as a coach and he was effectively saying that this team were good enough to win it.”

Erasmus got the director of coaching job in late 2017. When he accepted an offer to double as a head coach in 2018, he went to three former Bok coaches for advice, namely Andre Markgraaff, Carel du Plessis and Mallett himself. Markgraaf had selected Erasmus for the Springbok tour in 1996; Du Plessis had given him his first Test cap in 1997, while Mallett had backed him to start for much of his tenure between 1997 and 2000.

“Andre, as someone with a lot of experience in forward play, told Rassie that he had to settle on a tighthead and to ensure that the reserve tighthead was just as good,” says Mallett. “Andre understood that a team can’t afford to go backwards at the set-pieces if they want to win a Test.”

Under Erasmus, the Boks invested heavily in their set-piece and ultimately won the 2019 World Cup on a back of a plan that maximises the use of two tight-fives – and two world-class tightheads – over the course of 80 minutes.

“Carel pointed out that the Boks had failed to settle on a fly-half in 2016 and 2017,” adds Mallett. “He said that Rassie should pick his first choice and second choice in this position – and give them opportunities in the lead-up to the World Cup.

“Everyone always has an opinion about who should play No10 for the Boks. Carel told Rassie to make a decision and to ignore what was being said in the media and public.”

Erasmus picked Handré Pollard as his first-choice fly-half and Elton Jantjies as his second choice. He persisted with that formula right through the World Cup, even though some continued to question Pollard’s ability and temperament. Pollard was one of the stand-out players for the Boks in the World Cup final win against England.

“My advice was more around team selections and getting the balance right,” says Mallett. “We shared a lot of opinions about certain players – like Lukhanyo Am, who was already one of the most intelligent backline players in the country in 2018. There was a place for players like Cheslin Kolbe, but only in a situation where he had the space to work his magic.

“You couldn’t play off the No9 and then expect him to bash through the England or New Zealand midfield. From turnovers, that’s where those players would be at their best.”

When I spoke to Erasmus after his appointment, he listed Peet Kleynhans and Mallett as his greatest coaching influences. Kleynhans showed Erasmus how to inspire a team, while Mallett taught him a great deal about analysis as well as team values.

You shouldn’t have to give rousing speeches as a coach about what it means to represent your country. You technically and tactically prepare the players for every eventuality. The rest is up to them.

Nick Mallett

With regards to the latter, Erasmus felt that the Boks had become too pampered and that the absence of self-motivation had led to a decline in results. In short, the players had lost respect for the Bok jersey and the traditions associated with South African rugby.

“I was very strong on those values,” says Mallett, one of South Africa’s most successful coaches. “You shouldn’t have to give rousing speeches as a coach about what it means to represent your country. You technically and tactically prepare the players for every eventuality. The rest is up to them.

“Their job is to understand what this opportunity means and who they are playing for – their team-mates and their country.

“It’s hard to watch when the players are losing that motivation. I remember Ireland thrashing the Boks in 2017. The Boks basically threw in the towel in the last 10 minutes and the result was a record 38-3 defeat.”

Erasmus also went out of his way to create an honest and open environment. He tackled all issues around transformation and team selection in front of the whole team. None of these meetings were held behind closed doors. He explained to each player what their role would entail – and in some instances which games they would play over the course of the 2019 season.

“And he kept his word,” says Mallett. “As a player, you gain a hell of a lot of belief in a coach when he’s that open and honest.

“The leaders clearly believed in what he was trying to achieve on and off the field. There was criticism in the media about the type of game they were playing, but Rassie stayed true to his vision and the players maintained their trust in Rassie and Jacques.”

Mallett believes that New Zealand were found out when they tried to play a fast and loose game against England in the World Cup semi-finals. England then made the mistake of going into the final believing the title was theirs to lose.

“Rassie did well to keep his players on the ground that week. They were humble in the media yet never wavered in their belief that they could win the final,” says Mallett. “They continued to back the game plan and there was clarity about what was required in the game against England.

“They didn’t change the plan, as a lot of people have suggested. They simply looked to force England on to the back foot and punish those mistakes. Both tries by Makazole Mapimpi and Kolbe came from turnovers. Even in the latter stages, after they had a good lead, the team stuck to their task.

“It was a great example of how much they backed their coach. They trusted him because of his technical strengths and attention to detail, but also because of the manner in which he treated them as people. There was an emotional connection.”

That connection has strengthened over the past 18 months. While Erasmus has focused more on his role as director of rugby, he remains in charge of the Boks and will be hands-on throughout the Test season.

It’s an arrangement that sits well with Nienaber and the senior players. Mallett explains why the relationship between Erasmus and Nienaber is unique, and how it may amplify the Boks’ potency in the Lions series – as well as the Tests that follow.

“It has been a long process, but Rassie has got the right people in the right positions,” he says. “I can’t stress how important that combination between Rassie and Jacques is – they take each other’s opinions very seriously. Rassie has been in the limelight, but Jacques also deserves credit for his brilliant work as a defence coach. I don’t think they see it like that either, they see it as working together towards a common goal.

“They have always challenged one another, when they were at the Cheetahs, WP, Munster and now the Boks – but not to get the best of each other, but to get the best result for their team.

“That’s massive. Often you see the opposite happening, with DoRs and head coaches clashing, especially if one is getting more credit than the other in the media. To get that relationship right, to have a partnership for South Africa, is a massive bonus.”

Erasmus, in particular, has already put structures in place that will boost the national team and the franchises in the next three to five years. It’s vital, insists Mallett, that all of the teams and role players in South Africa continue to pull in the same direction.

“So much of the trust that currently exists is down to the systems Rassie has put in place and down to Jacques’ personality as a rugby man. Both genuinely want to help the franchises improve because they know that it’s to South African rugby’s benefit,” he says.

He said that the All Blacks had achieved something special when they won the 2011 World Cup and then continued to remain the No1 side in the world for the better part of a decade. It’s clear that that he wants the Boks to go on and do the same.

Nick Mallett

Again Mallett, who doesn’t give many interviews these days, goes out of his way to show how Erasmus has altered the attitude of a rugby nation and ultimately the course of the national team. He remembers attending the 2019 World Rugby Awards ceremony in Tokyo, where the World Cup-winning Boks won all of the big prizes on offer.

“What struck me was the manner in which the winners spoke. Siya Kolisi collected the Team of the Year award and Pieter-Steph du Toit collected the Player of the Year award. They didn’t speak about themselves, they credited their team-mates and explained that they did everything to bring the country glory. I could tell right then that Rassie and his attitude had got through to the players,” says Mallett.

“When Rassie got up to collect the Coach of the Year award, he paid homage to Eddie Jones and Steve Hansen. He said that he respected both of them and the example they had set for younger coaches such as himself.

“To Hansen, he said that the All Blacks had achieved something special when they won the 2011 World Cup and then continued to remain the No1 side in the world for the better part of a decade. It’s clear that that he wants the Boks to go on and do the same. They fell off the perch after winning the World Cup in 1995 and again after 2007 and 2009. Rassie wants them to move forward now.”

With Erasmus calling the shots, one would expect the Boks to approach the matches against the Lions with the same attention to detail and the same attitude that took them to the World Cup title.

The Lions would do well to recognise the threat – off the field as well as on it.

More stories by Jon Cardinelli

If you’ve enjoyed this article, please share it with friends or on social media. We rely solely on new subscribers to fund high-quality journalism and appreciate you sharing this so we can continue to grow, produce more quality content and support our writers.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free