On the eve of the momentous 1971 Test series between New Zealand and the British & Irish Lions, the coach of the All Blacks at the time, Ivan Vodanovich, famously declared that the game could become ‘another Passchendaele’. He was talking about interference in and around the ruck:

“The Lions’ crude attempts to nullify our second phase play are ruining a delightful part of rugby,” he said. “That is why they suffered so many injuries against Canterbury. The same thing will happen next Saturday if the All Blacks cannot get at the ball.”

It was of course, a gross exaggeration to compare activity at the ruck in rugby to one of the bloodiest battles of the First World War. But the current head coach of New Zealand, Ian Foster, may well be feeling sympathetic to the sentiments Vodanovich expressed after Saturday’s first test against Fiji.

The tackle area in the Top 14 league in France is rugby’s version of trench warfare. The better defensive sides dig in over the ball, and hang on for all they are worth against most of the attempts made by opponents, and even the referee to remove them.

It can make constructive attacking play a barren, unrewarding no man’s land into which no self-respecting coach will stray. Take a look back at the European Champions Cup Final played between Toulouse and La Rochelle. That will tell you all you need to know.

13 of the Fijian side who started the game at Forsyth Barr Stadium in Dunedin have spent a significant portion of their professional rugby careers playing Top 14 rugby in France.

Their determination to contest the tackle area dominated the character of the match as a whole – something which Ian Foster focussed on following the game.

“I enjoyed the test match because it did expose a few areas and it got us thinking about stuff and yet we muddled our way through a little bit but we found some good solutions. We’ll go away and have a look at it and see what we come up with next week.

“They had moments in that game where they put us under quite a bit of pressure. It highlighted a few areas that we’re obviously going to have to go and tidy up a little bit, but I guess the composure to come back and win [with] nine tries against a team that chucked everything at us was pretty pleasing.”

Ultimately, it was an uncomfortable evening for the home-based official. He ended up awarding a colossal 26 penalties at the breakdown – 14 to the attacking side and 12 to the defence.

That last statement probably represented the rose-tinted specs which are the privilege of a winning coach. The Fijians had managed to run only two full training sessions during a preparation in which most of their players began the mandatory 14-day quarantine on different days.

At the hour mark, the score was 31 points to 23 to the All Blacks, before Fiji finally ran out of puff in a final quarter that they lost by 26 points to nil. But make no mistake, the tackle area was played on Fiji’s terms for most of the match.

They turned over nine of the 71 rucks set by New Zealand, and a 13 per cent turnover rate is about three times more than the threshold for ‘respectable’. The referee, Paul Williams, gave every indication of being caught between a rock and a hard place – wanting to reward the contest for possession, but required to respect the laws governing release of the tackled player, and supporting bodyweight for defenders.

Ultimately, it was an uncomfortable evening for the home-based official. He ended up awarding a colossal 26 penalties at the breakdown – 14 to the attacking side and 12 to the defence.

It gave Fiji the stop-start rhythm they needed to compete, the tempo they are used to in Top 14. It also gave the likes of Levani Botia and Johnny Dyer a platform to raise some serious questions about the quality of the New Zealand cleanout and support play of the ball-carrier.

There was a visible difference in the sheer size of the Fiji backs compared with their Kiwi counterparts, even when the two sides ran onto the field. Four of the Fijians weighed over 100 kilos, compared to only one from New Zealand (centre Rieko Ioane).

Levani Botia is also one of the newer breed of number 12’s, second five-eighths who can play the position with the same impact in contact as a good openside flanker. In fact, ‘the Demolition Man’ (as he is nicknamed in the Top 14), has spent most of his rugby life shifting between the two spots.

It all made for an uncomfortable evening’s work for the New Zealand team in contact. In particular, the back-line proved to be a mixture of ball-players and strike-runners lacking in the hybrid skills that a player like Botia has in spades.

As a result, the All Blacks were always in danger of losing the ball whenever they had to clean out the ruck with only with their backs, or with one back and one forward:

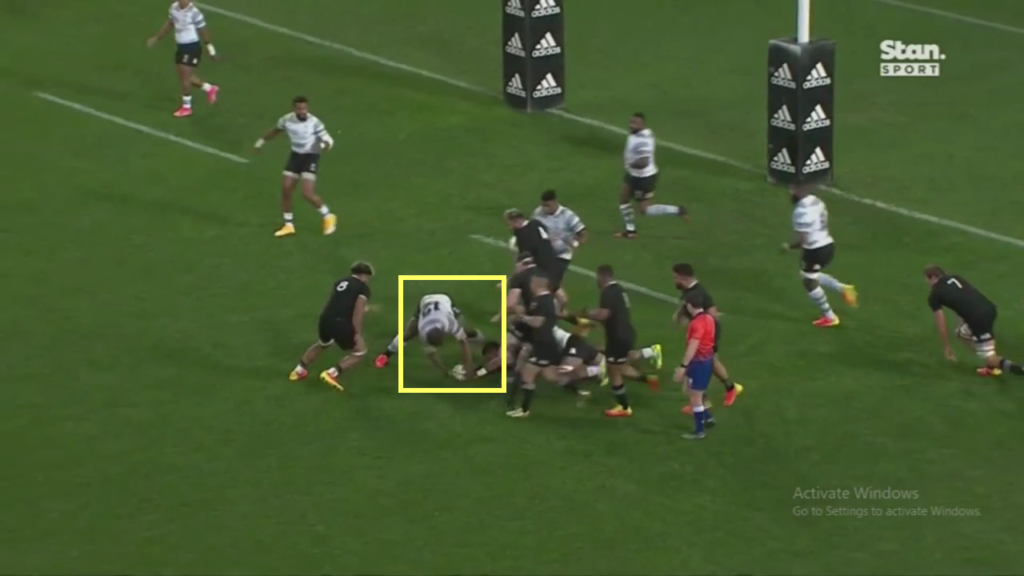

In the above example, Fiji’s number 8 Albert Tuisue and number 12 Botia are straight onto the ball after the tackle is made. Following the pattern of Super Rugby Trans-Tasman, the referee does not require a full and clear release of the ball-carrier before allowing both the tacklers to go back in on the ball. There is no chance of George Bridge and Ethan Blackadder removing the two threats at all.

The impact of the first man to the tackle zone is crucial, and here David Havili simply bounces off Johnny Dyer. Whenever the ball was played off the second man in attack, it increased the chances of a defender like Botia turning over possession:

It’s a similar story later in the first half, Botia dominates Damian McKenzie in the tackle, and resists all attempts by Bridge and Ioane to remove him thereafter:

Levani Botia won four turnovers on the ground during the game, but in fact he should have had five:

Sevu Reece is driven back in the tackle, and no ruck has been formed when Botia goes to pick up the loose ball:

The cleanout problems created by Botia were never resolved in-game, they persisted until the final whistle:

What happens when the defensive side become so dominant at the post-tackle? The answer to that question can be summarised by the following two-phase sequence in the second half:

With the All Blacks once again looking to play off the second or third pass, the ball travels into the left 15 metre zone, and the Fijians go on the attack in defence.

George Bridge is hit hard on the gain-line by his opposite number, and the combination cleanout by Rieko Ioane and Dane Coles struggles to remove the threat posed by Fiji captain Waisea Nayacalevu over the ball.

As the next phase begins, the picture looks like this:

The defensive pressure has forced New Zealand to over-resource the ruck, with no fewer than five All Blacks out of play for the next phase of attack. All of the Fijians are back on their feet and in the line.

That numerical advantage makes the outcome of the next play inevitable, when the ball is again moved off the second pass, and into the hands of replacement prop Tyrel Lomax. Hoskins Sotutu cannot remove Johnny Dyer in a one-on-one cleanout, and the result is another turnover penalty.

With Fiji’s lack of preparation time in mind, the game will have given Ian Foster and his coaches plenty of food for thought. An 87 per cent retention rate at the ruck is nowhere near satisfactory, and the All Blacks’ midfield combination – without Anton Lienert-Brown – lacked the physicality to cope with the problems set by Levani Botia and co.

With referee Paul Williams churning out penalties at the tackle area like confetti at a wedding, Fiji were able to impose the staccato stop-start rhythm that suits their European background the best. As a second-string France team have also shown in their current series against Australia, if you cannot clean up at the tackle against sides sourced from the Top 14, you cannot play the game you really want. It is an intriguing clash of cultures. There may have been no Passchendaele, but the war between north and south is very much alive.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free